The Politics of Expansion

Texans had sought admission to the Union almost since winning their independence from Mexico in 1836. Constant border warfare between Mexico and the Republic of Texas in the decade following the revolution underscored the precarious nature of independence. But any suggestion of adding another slave state to the Union outraged most Northerners, who applauded westward expansion but imagined the expansion of liberty, not slavery.

John Tyler, who became president in April 1841 when William Henry Harrison died one month after taking office, understood that Texas was a dangerous issue. Adding to the danger, Great Britain began sniffing around Texas, apparently contemplating adding the young republic to its growing empire. In 1844, Tyler, an ardent expansionist, decided to risk annexing the Lone Star Republic. However, howls of protest erupted across the North. Future Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner deplored the “insidious” plan to annex Texas and carve from it “great slaveholding states.” The Senate soundly rejected the annexation treaty.

During the election of 1844, the Whig nominee for president, Henry Clay, in an effort to woo northern voters, came out against annexation of Texas. “Annexation and war with Mexico are identical,” he declared. When news of Clay’s statement reached Andrew Jackson at his plantation in Tennessee, he chuckled, “Clay [is] a dead political Duck.” In Jackson’s shrewd judgment, no man who opposed annexation could be elected president.

The Democratic nominee, Tennessean James K. Polk, vigorously backed annexation. To make annexation palatable to Northerners, the Democrats cleverly yoked the annexation of Texas to the annexation of Oregon, thus tapping the desire for expansion in the free states of the North as well as in the slave states of the South. The Democratic platform called for the “reannexation of Texas” and the “reoccupation of Oregon.” The statement that the United States was merely reasserting existing rights was poor history but good politics.

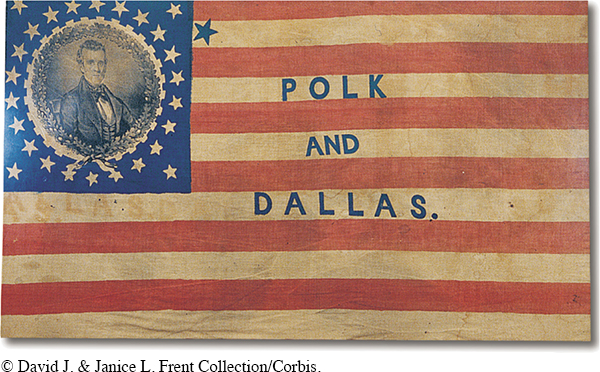

When Clay finally recognized the popularity of expansion, he waffled, hinting that he might accept the annexation of Texas after all. His retreat succeeded only in alienating antislavery opinion in the North. James G. Birney, the candidate of the fledging Liberty Party, denounced Clay as “rotten as a stagnant fish pond” and picked up the votes of thousands of disillusioned Clay supporters. In the November election, Polk won a narrow victory. [[LP Photo: 12.08 Polk and Dallas Banner, 1844/

> TRACE CHANGE

OVER TIME

How and why did American political leaders’ position on the annexation of Texas change between 1836 and 1845?

In his inaugural address on March 4, 1845, Polk underscored his faith in America’s manifest destiny. “This heaven-favored land,” he proclaimed, enjoyed the “most admirable and wisest system of well-regulated self-government . . . ever devised by human minds.” He asked, “Who shall assign limits to the achievements of free minds and free hands under the protection of this glorious Union?”

The nation did not have to wait for Polk’s inauguration to see results from his victory. One month after the election, President Tyler announced that the triumph of the Democratic Party provided a mandate for the annexation of Texas “promptly and immediately.” In February 1845, after a fierce debate between antislavery and proslavery forces, Congress approved a joint resolution offering the Republic of Texas admission to the United States. Texas entered as the fifteenth slave state.

While Tyler delivered Texas, Polk had promised Oregon, too. Westerners particularly demanded that the new president make good on the Democratic pledge “Fifty-four forty or Fight”—that is, all of Oregon, right up to Alaska (54°40' was the southern latitude of Russian Alaska). But Polk was close to war with Mexico and could not afford a war with Britain over U.S. claims in Canada. He renewed an old offer to divide Oregon along the forty-ninth parallel. Westerners cried betrayal, but when Britain accepted the compromise, the nation gained an enormous territory peacefully. When the Senate approved the treaty in June 1846, the United States and Mexico were already at war.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 329

Section Chronology