Women, War, and the Battle for Suffrage

Women had made real strides during the Progressive Era, and war presented new opportunities. More than 25,000 women served in France. About half were nurses. The others drove ambulances; ran canteens for the Salvation Army, Red Cross, and YMCA; worked with French civilians in devastated areas; and acted as telephone operators and war correspondents. Like men who joined the war effort, they believed that they were taking part in a great national venture. “I am more than willing to live as a soldier and know of the hardships I would have to undergo,” one canteen worker declared when applying to go overseas, “but I want to help my country. . . . I want . . . to do the real work.” And like men, women struggled against disillusionment in France. One woman explained: “Over in America, we thought we knew something about the war . . . but when you get here the difference is [like the one between] studying the laws of electricity and being struck by lightning.”

Nora Saltonstall, daughter of a prominent Massachusetts family, was one of the American women who volunteered with the Red Cross and sailed for France. Attached to a mobile surgical hospital that followed closely behind the French armies, she became a driver, chauffeuring personnel, transporting the wounded, and hauling supplies. Soon she was driving on muddy, shell-pocked roads in the dark without lights. Her life, she said, consisted of “choked carburetors, broken springs, long hours on the road, food snatched when you can get it, and sleep.” She “hated the war,” but she told her mother, “I love my job.” She was proud of “doing something necessary here.”

At home, long-standing barriers against hiring women fell when millions of workingmen became soldiers and few new immigrant workers crossed the Atlantic. Tens of thousands of women found work in defense plants as welders, metalworkers, and heavy machine operators and with the railroads. A black woman, a domestic before the war, celebrated her job as a laborer in a railroad yard: “We . . . do not have to work as hard as at housework which requires us to be on duty from six o’clock in the morning until nine or ten at night, with might[y] little time off and at very poor wages.” Other women found white-collar work. Between 1910 and 1920, the number of women clerks doubled. Before the war ended, more than a million women had found work in war industries. One women’s rights advocate exaggerated when she declared, “At last . . . women are coming into the labor and festival of life on equal terms with men,” but women had made real economic strides.

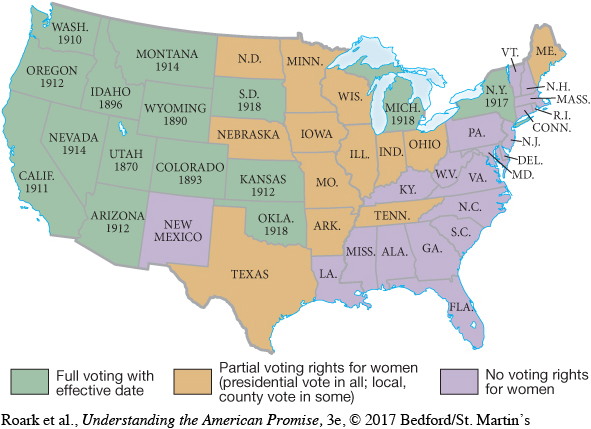

The most dramatic advance for women came in the political arena. Adopting a state-by-state approach before the war, suffragists had achieved some success (Map 22.4). More commonly, voting rights for women met strong hostility and defeat. After 1910, suffrage leaders added a federal campaign to amend the Constitution to the traditional state-by-state strategy for suffrage. [[LP Map: M22.04 Women’s Voting Rights Before the Nineteenth Amendment – MAP ACTIVITY/

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

What factor was the most critical for explaining why woman suffrage was finally achieved in 1920?

The radical wing of the suffragists, led by Alice Paul, picketed the White House, where the marchers unfurled banners that proclaimed “America Is Not a Democracy. Twenty Million Women Are Denied the Right to Vote.” They chained themselves to fences and went to jail, where many engaged in hunger strikes. “They seem bent on making their cause as obnoxious as possible,” Woodrow Wilson declared. His wife, Edith, detested the idea of “masculinized” voting women. But membership in the mainstream organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), led by Carrie Chapman Catt, soared to some two million. Seeing the handwriting on the wall, the Republican and Progressive parties endorsed woman suffrage in 1916.

In 1918, Wilson finally gave his support to suffrage, calling the amendment “vital to the winning of the war.” He conceded that it would be wrong not to reward the wartime “partnership of suffering and sacrifice” with a “partnership of privilege and right.” By linking their cause to the wartime emphasis on national unity, the advocates of woman suffrage finally triumphed. In 1919, Congress passed the Nineteenth Amendment, granting women the vote, and by August 1920 the required two-thirds of the states had ratified it. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: The Final Push for Woman Suffrage.”)

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 627

Section Chronology