Home-Front Security

Shortly after declaring war against the United States, Hitler dispatched German submarines to hunt American ships along the Atlantic coast, where Paul Tibbets and other American pilots tried to destroy them. The U-boats had devastating success for about eight months, sinking hundreds of U.S. ships and threatening to disrupt the Lend-Lease lifeline to Britain and the Soviet Union. But by mid-1942, the U.S. Navy had chased German submarines into the mid-Atlantic.

Within the continental United States, Americans remained sheltered from the chaos and destruction the war brought to hundreds of millions in Europe and Asia. Nevertheless, the government worried constantly about espionage and internal subversion. Posters warned Americans that “Loose lips sink ships” and “Enemy agents are always near; if you don’t talk, they won’t hear.” The campaign for patriotic vigilance focused on German and Japanese foes, but Americans of Japanese descent became targets of official and popular persecution because of Pearl Harbor and long-standing racial prejudice against people of Asian descent.

About 320,000 people of Japanese ancestry lived in U.S. territory in 1941, two-thirds of them in Hawai’i, where they largely escaped wartime persecution because they were essential and valued members of society. On the mainland, however, Japanese Americans were a tiny minority—even along the West Coast, where most of them worked on farms and in small businesses. Although an official military survey concluded that Japanese Americans posed no danger, popular hostility fueled a campaign to round up all mainland Japanese Americans—two-thirds of them U.S. citizens. “A Jap’s a Jap. . . . It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not,” one official declared.

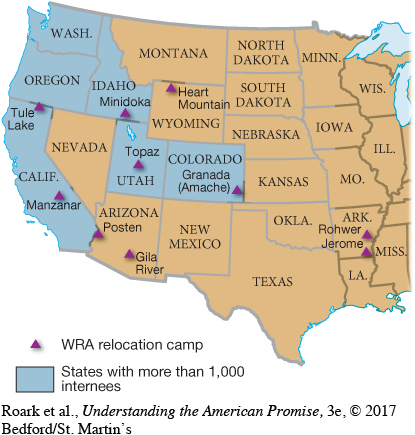

On February 19, 1942, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized sending all Americans of Japanese descent to ten makeshift internment camps located in remote areas of the West and South (Map 25.3). Allowed little time to sell or secure their properties, Japanese Americans lost homes and businesses worth about $400 million and lived out the war penned in by barbed wire and armed guards. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: Japanese Internment.”) Although several thousand Japanese Americans served with distinction in the U.S. armed forces and no case of subversion by a Japanese American was ever uncovered, the Supreme Court, in its 1944 Korematsu decision, upheld Executive Order 9066’s blatant violation of constitutional rights as justified by “military necessity.” [[LP Map: M25.03 Western Relocation Authority Centers/

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 717

Section Chronology