The Fair Deal Flounders

Republicans capitalized on public frustrations with strikes and shortages in the 1946 congressional elections, accusing the Truman administration of “confusion, corruption, and communism.” Republicans captured control of Congress for the first time in fourteen years. Many had campaigned against the New Deal, and in the Eightieth Congress they weakened some reform programs and enacted tax cuts favoring higher-income groups.

Organized labor took the most severe blow when Congress passed the Taft-Hartley Act over Truman’s veto in 1947. Called a “slave labor” law by unions, the measure amended the Wagner Act (see chapter 24), putting restraints on unions that reduced their power to bargain with employers and made it more difficult to organize workers. States could now pass “right-to-work” laws, which banned the practice of requiring all workers to join a union once a majority had voted for it. Many states, especially in the South and West, rushed to enact such laws, encouraging industries to relocate there. Taft-Hartley maintained the New Deal principle of government protection for collective bargaining, but it tipped the balance of power more in favor of management.

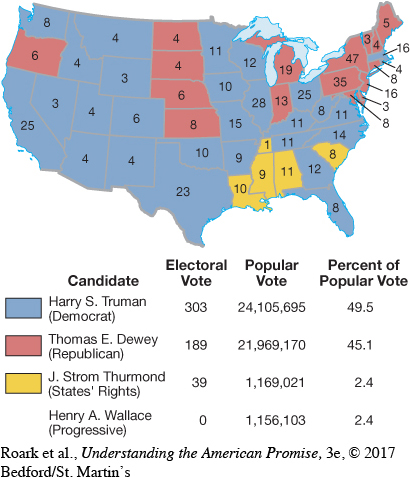

In the 1948 elections, Truman faced not only a resurgent Republican Party headed by New York governor Thomas E. Dewey but also two revolts within his own party. On the left, Henry A. Wallace, whose foreign policy views had cost him his cabinet seat, led the new Progressive Party. On the right, South Carolina governor J. Strom Thurmond headed the States’ Rights Party—the Dixiecrats—formed by southern Democrats who walked out of the 1948 Democratic Party convention when it passed a liberal civil rights plank.

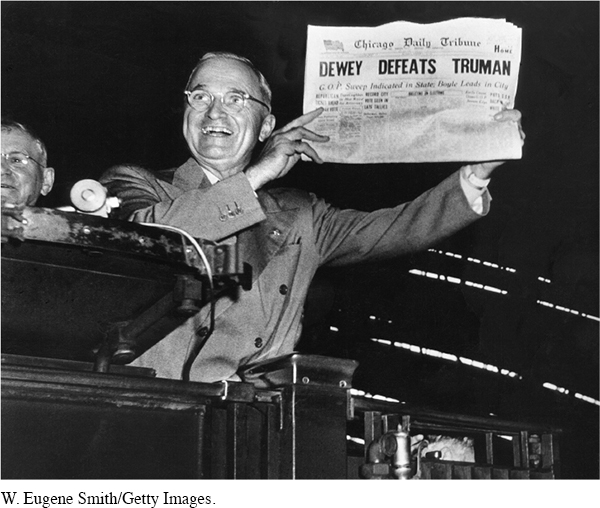

Truman launched a vigorous campaign, yet his prospects were so bleak that on election night the Chicago Daily Tribune printed its next day’s issue with the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.” But even though the Dixiecrats won four southern states, Truman took 303 electoral votes to Dewey’s 189, and his party regained control of Congress (Map 26.2). His unexpected victory attested to the broad support for his foreign policy and the enduring popularity of New Deal reform. [[LP Photo: P26.06 Truman’s 1948 Victory/

While most New Deal programs survived Republican attacks, Truman failed to enact his Fair Deal agenda. Congress made modest improvements in Social Security and raised the minimum wage, but it passed only one significant reform measure. The Housing Act of 1949 authorized 810,000 units of government-constructed housing over the next six years and represented a landmark commitment by the government to address the housing needs of the poor. Yet it fell far short of actual need, and slum clearance frequently displaced the poor without providing alternatives.

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

How did the divisions in the Democratic Party reflect the major issues that faced the United States in the late 1940s?

With southern Democrats posing a primary obstacle, Congress rejected Truman’s proposals for civil rights, a powerful medical lobby blocked plans for a universal health care program, and conflicts over race and religion thwarted federal aid to education. Truman’s efforts to revise immigration policy were mixed. The McCarran-Walter Act of 1952 ended the outright ban on immigration and citizenship for Japanese and other Asians, but it authorized the government to bar suspected Communists and homosexuals and maintained the discriminatory quota system established in the 1920s.

Truman’s concentration on foreign policy rather than domestic proposals contributed to the failure of his Fair Deal. By late 1950, the Korean War embroiled the president in controversy and depleted his power as a legislative leader (see “How did U.S. Cold War policy lead to the Korean War?”). Truman’s failure to make good on his domestic proposals set the United States apart from most European nations, which by the 1950s had in place comprehensive health, housing, and employment security programs to underwrite the material well-being of their populations.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 755

Section Chronology