Black Power and Urban Rebellions

By 1966, black protest engulfed the entire nation, demanding not just legal equality but also economic justice and abandoning passive resistance as a basic principle. These developments were not completely new. African Americans had waged campaigns for decent jobs, housing, and education outside the South since the 1930s. Some African Americans had always armed themselves in self-defense, and many protesters doubted that their passive response to violent attacks would change the hearts of racists. Still, the black freedom struggle began to appear more threatening to the white majority.

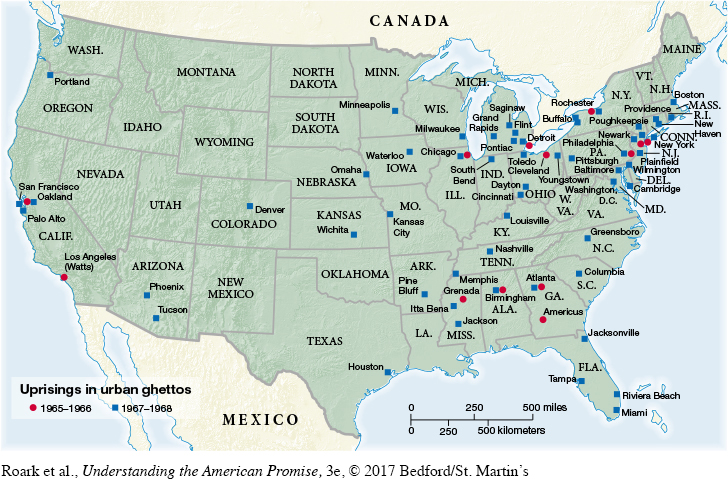

The new emphases resulted from a combination of heightened activism and unrealized promise. Legal equality could not quickly ameliorate African American poverty, and black rage at oppressive conditions erupted in waves of urban uprisings from 1965 to 1968 (Map 28.3). In a situation where virtually all-white police forces patrolled black neighborhoods, incidents between police and local blacks typically sparked the riots and resulted in looting, destruction of property, injuries, and deaths. The worst riots occurred in Watts (Los Angeles) in August 1965, Newark and Detroit in July 1967, and the nation’s capital in April 1968, but violence visited hundreds of cities, and African Americans suffered most of the casualties.[[LP Map: M28.03 Urban Uprisings, 1965–1968 – MAP ACTIVITY/

In the North, Malcolm X posed a powerful challenge to the ethos of nonviolence. Calling for black pride and autonomy, separation from the “corrupt [white] society,” and self-defense against white violence, Malcolm X attracted a large following, especially in urban ghettos. At a June 1966 rally in Greenwood, Mississippi, SNCC chairman Stokely Carmichael gave the ideas espoused by Malcolm X a new name when he shouted, “We want black power.” Carmichael rejected integration and assimilation because they implied white superiority. African Americans were encouraged to develop independent businesses and control their own schools, communities, and political organizations. The phrase “Black is beautiful” emphasized pride in African American culture and connections to dark-skinned people around the world who were claiming their independence from colonial domination. Black power quickly became the rallying cry in SNCC and CORE as well as other organizations such as the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, organized to combat police brutality.

The press paid inordinate attention to the black power movement, and civil rights activism met with a severe backlash from whites. Although the urban riots of the mid-1960s erupted spontaneously, triggered by specific incidents of alleged police mistreatment, horrified whites blamed black power militants. By 1966, 85 percent of the white population—up from 34 percent two years earlier—thought that African Americans were pressing for too much too quickly.

> COMPARE AND CONTRAST

How did the goals and strategies of the black power activists differ from those of Martin Luther King Jr. and his followers? In what ways did they overlap?

Martin Luther King Jr. agreed with black power advocates about the need for economic justice and “a radical reconstruction of society,” yet he clung to nonviolence and integration as the means to this end. In 1968, the thirty-nine-year-old leader went to Memphis to support striking municipal sanitation workers. There, on April 4, he was murdered by an escaped white convict.

Although black power organizations captured the headlines, they failed to gain the massive support from African Americans that King and other leaders had attracted. Nor could they alleviate the poverty and racism entrenched in the entire country. Black radicals were harassed by the FBI and jailed; some encounters left both black militants and police dead. Yet black power’s emphasis on racial pride and its critique of American institutions resonated loudly and helped shape the protest activities of other groups.

> QUICK REVIEW

How and why did the civil rights movement change in the mid-1960s?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 807

Section Chronology