Gay Men and Lesbians Organize

More permissive sexual norms did not stretch easily to include tolerance of homosexuality. Gay men and lesbians escaped discrimination and ridicule only by concealing their very identities. Those who couldn’t or wouldn’t found themselves fired from jobs, arrested for their sexual activities, deprived of their children, or accused of being “perverted.” Despite this, some gays and lesbians began to organize.

An early expression of gay activism challenged the government’s aggressive efforts to keep homosexuals out of civil service. In October 1965, picketers outside the White House held signs calling discrimination against homosexuals “as immoral as discrimination against Negroes and Jews.” Not until ten years later, however, did the Civil Service Commission formally end its antigay policy.

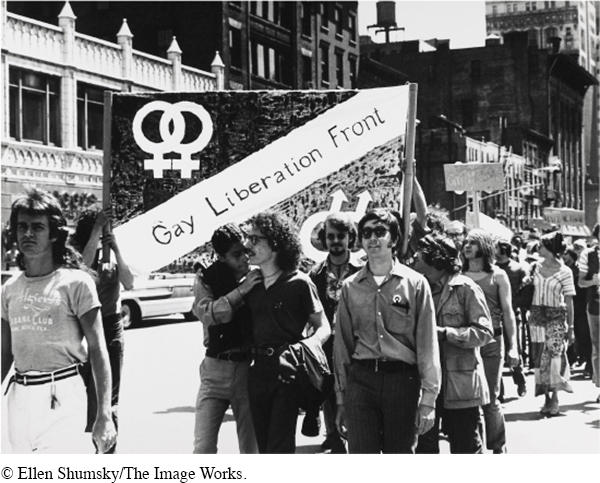

A turning point in gay activism came in 1969 when police raided a gay bar, the Stonewall Inn, in New York City’s Greenwich Village, and gay men and lesbians fought back. “Suddenly, they were not submissive anymore,” a police officer remarked. Energized by the defiance shown at the Stonewall riots, gay men and lesbians organized a host of new groups, such as the Gay Liberation Front and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. [[LP Photo: P28.10 Gay Liberation Front Marches in New York/

In 1972, Ann Arbor, Michigan, passed the first antidiscrimination ordinance, and two years later Elaine Noble’s election to the Massachusetts legislature marked the first time an openly gay candidate won state office. In 1973, gay activists persuaded the American Psychiatric Association to withdraw its designation of homosexuality as a mental disease. It would take decades for these initial gains to improve conditions for most homosexuals, but by the mid-1970s gay men and lesbians had a movement through which they could claim equal rights and express pride in their identities.

> QUICK REVIEW

How did the black freedom struggle influence other reform movements of the 1960s and 1970s?

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 814

Section Chronology