The Peace Accords

Nixon and Kissinger continued to believe that intensive firepower could bring the North Vietnamese to their knees. In March 1972, responding to a North Vietnamese offensive, the United States resumed sustained bombing of the North, mined Haiphong and other harbors for the first time, and announced a naval blockade. With peace talks stalled, in December Nixon ordered the most devastating bombing yet. Though costly to both sides, it brought renewed negotiations. On January 27, 1973, representatives of the United States, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, and the Vietcong (now called the Provisional Revolutionary Government) signed a formal peace accord in Paris. The agreement required removal of all U.S. troops and military advisers from South Vietnam but allowed North Vietnamese forces to remain. Both sides agreed to return prisoners of war. Nixon called the agreement “peace with honor,” but in fact it allowed only a face-saving withdrawal. Unlike the ending of World War II, “There’s nothing to celebrate,” said an American Legion commander.

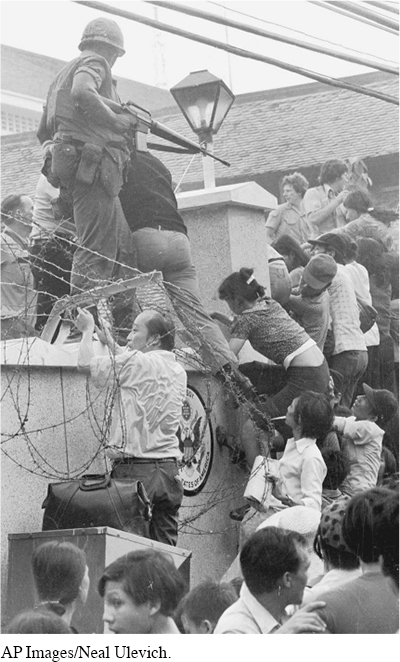

Fighting resumed immediately among the Vietnamese. Nixon’s efforts to support the South Vietnamese government, and indeed his ability to govern at all, were increasingly eroded by what came to be known as the Watergate scandal, which forced him to resign in 1974 (as discussed in chapter 30). In 1975, North Vietnam launched a new offensive, seizing Saigon on April 30. The Americans remaining in the U.S. Embassy and their Marine guard hastily evacuated, along with 150,000 of their South Vietnamese allies. Confusion, humiliation, and tragedy marked the rushed departure. The United States lacked sufficient transportation capacity and time to evacuate all those who had supported the South Vietnamese government and were desperate to leave. A U.S. diplomat who escaped Saigon commented, “The rest of our lives we will be haunted by how we betrayed those people.” Eventually more than 600,000 Vietnamese fled to the United States, but others lost their lives trying to escape, and many who could not get out suffered from political repression or poverty.

During the four years it took Nixon to end the war, he had expanded the conflict into Cambodia and Laos and launched massive bombing campaigns. Although increasing numbers of legislators criticized the war, Congress never denied the funds to fight it. Only after the peace accords did the legislative branch try to reassert its constitutional authority in the making of war. The War Powers Act of 1973 required the president to secure congressional approval for any substantial, long-term deployment of troops abroad. The new law, however, did little to dispel the distrust of government that resulted from Americans’ realization that their leaders had not told the truth about Vietnam. [[LP Photo: P29.09 Evacuating South Vietnam/

The war produced widespread criticism of the draft from both the left and right. As the United States withdrew from Vietnam, Nixon and Congress agreed to abandon conscription, which had been part of the Cold War since its beginning. Replacing the principle of obligation with the offer of opportunity, military leaders predicted that an all-volunteer army would make a more disciplined and professional fighting force. At the same time, ending service as a common sacrifice distanced most Americans from the horrors of warfare and from the military, whose ranks would be disproportionately filled by poorer Americans and people of color.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 849

Section Chronology