An All-Out Commitment in Vietnam

The president, who wanted to make his mark on domestic policy, was compelled to deal with the commitments his predecessors had made in Vietnam. Some advisers, politicians, and international leaders questioned the wisdom of greater intervention there, recognizing the situation as a civil war rather than Communist aggression. Most U.S. allies did not consider Vietnam crucial to containing communism and were not prepared to share the military burden. Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield wondered, “What national interests in Asia would steel the American people for the massive costs of an ever-deepening involvement?” Disregarding the opportunity for disengagement that these critics saw in 1964, Johnson expressed his own doubt privately: “I don’t think it’s worth fighting for and I don’t think we can get out.”

Like Kennedy, Johnson remembered the political blows that Truman had taken when the Communists took over China, and he determined not “to be the president who saw Southeast Asia go the way China did.” Like most of his advisers, he saw American credibility as a bulwark against the threat of communism, and he believed that abandoning Vietnam would undermine his ability to achieve his Great Society.

Johnson understood the ineffectiveness of his South Vietnamese allies and agonized over sending young men into combat. Yet he continued to dispatch more military advisers, weapons, and economic aid and, in August 1964, seized an opportunity to increase the pressure on North Vietnam. While spying in the Gulf of Tonkin, off the coast of North Vietnam, two U.S. destroyers reported that North Vietnamese gunboats had fired on them (see Map 29.2). Johnson quickly ordered air strikes on North Vietnamese torpedo bases and oil storage facilities. Concealing the uncertainty about whether the second attack had even occurred, he won from Congress the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, authorizing him to take “all necessary measures to repel any armed attacks against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

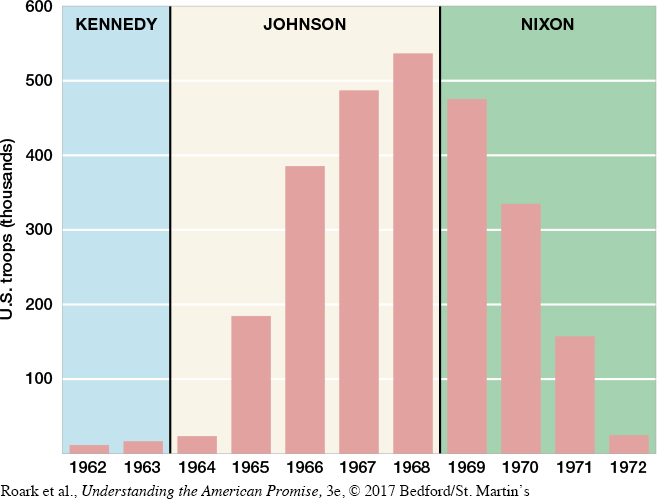

Soon after winning the election of 1964, Johnson widened the war. He dismissed reservations expressed by prominent Democrats and rejected peace overtures from North Vietnam, which insisted on American withdrawal and a coalition government in South Vietnam as steps toward unification of the country. In February 1965, Johnson authorized Operation Rolling Thunder, a gradually intensified bombing of North Vietnam. Less than a month later, Johnson ordered the first combat troops to South Vietnam, and in July he shifted U.S. troops from defensive to offensive operations, dispatching 50,000 more soldiers (Figure 29.1). Although the administration downplayed the import of these decisions, they marked a critical turning point. Now it was genuinely America’s war. [[LP Figure: F29.1 U.S. Troops in Vietnam, 1962–1972/

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 834

Section Chronology