The Cold War Ends

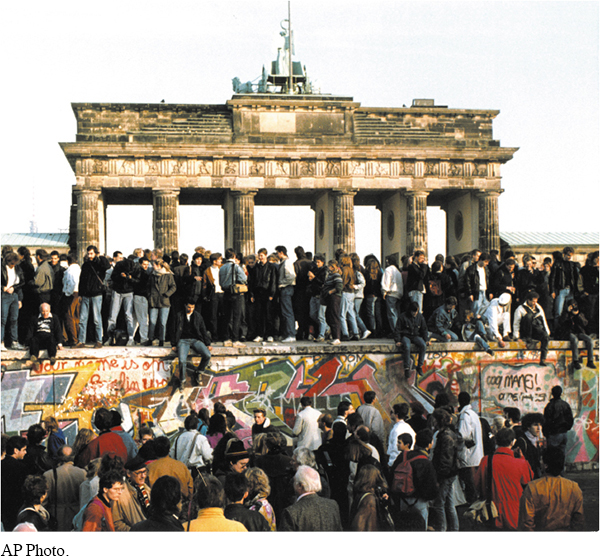

While domestic policy remained fairly constant during Bush’s presidency, the world experienced enormous changes. In 1989, the progressive forces that Gorbachev had encouraged in the Communist world (see “A Thaw in Soviet-American Relations” in chapter 30) swept through Eastern Europe, where popular uprisings demanded an end to state repression and inefficient economic bureaucracies. Communist governments toppled like dominoes (Map 31.1), virtually without bloodshed, because Gorbachev refused to prop them up with Soviet armies. East Germany opened its border with West Germany, and in November 1989 ecstatic Germans danced on the Berlin Wall. [[LP Photo: M31.01 Events in Eastern Europe, 1989–2002 – MAP ACTIVITY/

Unification of East and West Germany sped to completion in 1990. Soon Poland, Hungary, and other former iron curtain countries lined up to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a development that Russia found threatening. Eight former Soviet satellites joined the European Union and the common economic market it had established in 1992. Inspired by the liberation of Eastern Europe, republics within the Soviet Union soon established their own independence. With nothing left to govern, Gorbachev resigned. The Soviet Union had dissolved, and with it the Cold War conflict that had defined U.S. foreign policy for decades. [[LP Photo: P31.02 Fall of the Berlin Wall/

Democracy also prevailed in South Africa, which began to dismantle apartheid; this process led in 1994 to the election of the country’s first black president, Nelson Mandela. Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, joked that he was “running out of villains. I’m down to Castro and Kim Il-sung,” the North Korean dictator who, along with China’s leaders, resisted the liberalizing tides sweeping the world. In 1989, Chinese soldiers killed hundreds of pro-democracy demonstrators in Beijing, and the Communist government arrested some ten thousand reformers. North Korea remained a Communist dictatorship, committed to developing nuclear weapons.

“The post–Cold War world is decidedly not post-nuclear,” declared one U.S. official. In 1990, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START) treaty, which cut about 30 percent of each superpower’s nuclear arsenal. And in 1996, the United Nations General Assembly overwhelmingly approved a total nuclear test ban treaty. Yet India and Pakistan, hostile neighbors, refused to sign the treaty, and both exploded atomic devices in 1998. Moreover, the Republican-controlled U.S. Senate defeated ratification of the treaty. The potential for rogue nations and terrorist groups to develop nuclear weapons posed an ongoing threat.

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 887

Section Chronology