The Rigors of Servitude

Servants—whether men or women, whites or blacks, English or African—tended to work together and socialize together. During the first half century of settlement, racial intermingling occurred, although the small number of blacks made it infrequent. In general, the commonalities of servitude caused servants—regardless of their race and gender—to consider themselves apart from free people, whose ranks they longed to join eventually.

Servant life was harsh by the standards of seventeenth-century England and even by the frontier standards of the Chesapeake. Unlike servants in England, Chesapeake servants had no control over who purchased their labor—and thus them—for the period of their indenture. They were “sold here upp and downe like horses,” one observer reported. A Virginia servant complained in 1623 that his master “hath sold me for £150 sterling like a damnd slave.” But tobacco planters’ need for labor muffled complaints about treating servants as property.

“The Servants of this Province,” one boasted, “live more like Freemen than the most Mechanick Apprentices in London, wanting for nothing that is convenient and necessary, and . . . are extraordinary well used and respected.” For many other servants, such promises withered when confronted by the rigors of labor in tobacco fields. Severe laws aimed to keep servants in their proper places. James Revel, an eighteen-year-old thief punished by being indentured to a Virginia tobacco planter, declared he was a “slave” sent to hoe “tobacco plants all day” from dawn to dusk. Punishments for petty crimes stretched servitude far beyond the original terms of indenture. Richard Higby, for example, received six extra years of servitude for killing three hogs. After midcentury, the Virginia legislature added three or more years to the indentures of most servants by requiring them to serve until they were twenty-four years old.

Women servants were subject to special restrictions and risks. They were prohibited from marrying until their servitude had expired. A servant woman, the law assumed, could not serve two masters at the same time: one who owned her indentured labor and another who was her husband. As a rule, if a woman servant gave birth to a child, she had to serve two extra years and pay a fine. Inevitably, the predominance of men in the colonial population pressured servant women to engage in sexual relations, and about a third of immigrant women were pregnant when they married.

> UNDERSTAND

POINTS OF VIEW

How did Virginia planters’ views of and expectations for their servants differ from the servants’ understanding of their status and obligations?

Harsh punishments reflected four fundamental realities of the servant labor system. First, planters’ hunger for labor caused them to demand as much labor as they could get from their servants. Second, servants hoped to survive their servitude and use their freedom to obtain land and start a family. Third, since servants saw themselves as free people in a temporary status of servitude, they often made grudging, halfhearted workers. Finally, planters put up with this contentious arrangement because the alternatives were less desirable.

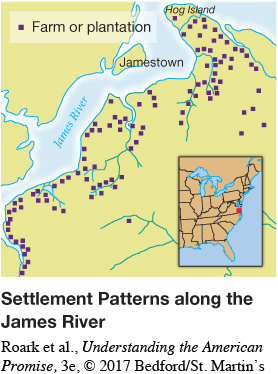

Planters could not easily hire free men and women because land was readily available and free people preferred to work for themselves on their own land. Nor could planters depend on much labor from family members because families were few, were started late, and thus had few children. And, until the 1680s and 1690s, slaves were expensive and hard to come by. Before then, masters who wanted to grow more tobacco had few alternatives to buying indentured servants. (See “Analyzing Historical Evidence: Enslavement by Marriage.”)

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 62

Section Chronology