Ohio Indians in the Northwest

Tribes of the Ohio Valley were even less willing to negotiate with the new federal government. Left vulnerable by the 1784 Treaty of Fort Stanwix (see “The Treaty of Fort Stanwix” in chapter 8), in which Iroquois tribes in New York had relinquished Ohio lands to the Americans, the Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, and other groups local to Ohio stood their ground. To confuse matters further, British troops still occupied half a dozen forts in the Northwest, protecting an ongoing fur trade between British traders and Indians and thereby sustaining Indians’ claims to that land.

Under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance (see “Land Ordinances and the Northwest Territory” in chapter 8), the federal government started to survey and map eastern Ohio, and settlers were eager to buy. So Washington sent units of the U.S. Army into Ohio’s western half to subdue the various tribes. Fort Washington, built on the Ohio River in 1789 at the site of present-day Cincinnati, became the command post for three major invasions of Indian country (Map 9.2). The first occurred in the fall of 1790, when General Josiah Harmar marched with 1,400 men into Ohio’s northwest region, burning Indian villages. His inexperienced troops were ambushed by Miami and Shawnee Indians led by their chiefs, Little Turtle and Blue Jacket. Harmar lost one-eighth of his soldiers and retreated.[[LP Map: M09.02 Western Expansion and Indian Land Cessions to 1810 – MAP ACTIVITY/

Harmar’s defeat spurred enhanced efforts to clear Ohio for permanent American settlement. General Arthur St. Clair, the military governor of the Northwest Territory, had pursued peaceful tactics in the 1780s, signing treaties with Indians for land in eastern Ohio—dubious treaties, as it happened, since the Indian negotiators were not authorized to yield land. In the wake of Harmar’s bungled operation, St. Clair geared up for military action, and in the fall of 1791 he and two thousand men (accompanied by two hundred women camp followers) traveled north from Fort Washington along Harmar’s route, erecting two more fortified structures—Fort Jefferson and Fort Hamilton—deep in Indian country. Despite that show of military might, a surprise attack by Indians at the headwaters of the Wabash River left 55 percent of the Americans dead or wounded; only three of the women escaped alive. “The savages seemed not to fear anything we could do,” wrote an officer afterward. “The ground was literally covered with the dead.” The Indians captured valuable weaponry and scalped and dismembered the dying on the field of battle. With more than nine hundred lives lost, this was the most stunning American loss in the history of the U.S. Indian wars.

Washington doubled the U.S. military presence in Ohio and appointed a new commander, General Anthony Wayne of Pennsylvania, nicknamed “Mad Anthony” for his headstrong, hard-drinking style of leadership. About the Ohio natives, Wayne wrote, “I have always been of the opinion that we never should have a permanent peace with those Indians until they were made to experience our superiority.” Throughout 1794, Wayne’s army engaged in skirmishes with various tribes. Chief Little Turtle of the Miami tribe advised negotiation; in his view, Wayne’s large army looked overpowering. But Blue Jacket of the Shawnees counseled continued warfare, and his view prevailed.

The decisive action came in August 1794 at the battle of Fallen Timbers, near the Maumee River, where a recent tornado had felled many trees. The confederated Indians—mainly Ottawas, Potawatomis, Shawnees, and Delawares numbering around eight hundred—ambushed the Americans but were underarmed, and Wayne’s troops made effective use of their guns and bayonets. The Indians withdrew and sought refuge at nearby Fort Miami, still held by the British, but their former allies locked the gate and refused protection. The surviving Indians fled to the woods, their ranks decimated.

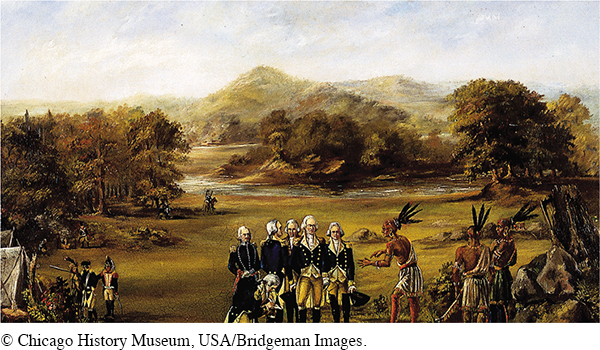

Fallen Timbers was a major defeat for the Indians. The Americans had destroyed cornfields and villages on the march north, and with winter approaching, the Indians’ confidence was sapped. They reentered negotiations in a much less powerful bargaining position. In 1795, about a thousand Indians representing nearly a dozen tribes met with Wayne and other American emissaries to work out the Treaty of Greenville. The Americans offered treaty goods (calico shirts, axes, knives, blankets, kettles, mirrors, ribbons, thimbles, and abundant wine and liquor casks) worth $25,000 and promised additional shipments every year. The government’s idea was to create a dependency on American goods to keep the Indians friendly. In exchange, the Indians ceded most of Ohio to the Americans; only the northwest part of the territory was reserved solely for the Indians.[[LP Photo: P09.05 Treaty of Greenville, 1795 – VISUAL ACTIVITY/

> PLACE EVENTS

IN CONTEXT

Why did George Washington and his advisers engage in military action against the Native Americans so soon after the American Revolution?

The treaty brought temporary peace to the region, but it did not restore a peaceful life to the Indians. The annual allowance from the United States too often came in the form of liquor. “More of us have died since the Treaty of Greenville than we lost by the years of war before, and it is all owing to the introduction of liquor among us,” said Chief Little Turtle in 1800. “This liquor that they introduce into our country is more to be feared than the gun and tomahawk.”

Understanding the American Promise 3ePrinted Page 238

Section Chronology