Will the Real Hooded Man Please Stand Up?

Will the Real Hooded Man Please Stand Up?

1

It was arguably one of the least newsworthy pictures in the world, if only because it had already been seen by everybody. And yet, on March 11, 2006, the New York Times published on the front page of the first section, in the upper left-hand corner, a photograph of a man holding the photograph that had been seen around the world.

2

Ali Shalal Qaissi, the man shown holding the photograph, had come forward as “The Hooded Man.”

3

The Hooded Man, no longer anonymous, became a national news story — not because he was a victim of torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib but because he was in an infamous photograph. The accompanying story in the Times made this clear. The article was written by Hassan M. Fattah.

Amman, Jordan, March 8 — Almost two years later, Ali Shalal Qaissi’s wounds are still raw. There is the mangled hand, an old injury that became infected by the shackles chafing his skin. There’s the slight limp, made worse by days tied in uncomfortable positions. And most of all, there are the nightmares of his nearly six-month ordeal at Abu Ghraib prison in 2003 and 2004.

Mr. Qaissi, 43, was prisoner 151716 of Cellblock 1A. The picture of him standing hooded atop a cardboard box, attached to electrical wires with his arms stretched wide in an eerily prophetic pose, became the indelible symbol of the torture at Abu Ghraib, west of Baghdad.

Put simply: without the iconic photograph, it’s likely there would have been little or no interest in Qaissi or his story. Qaissi was not the first ex-prisoner at Abu Ghraib to be interviewed by human rights workers, but he was the first to be profiled on page one of the Times. (Although the Times did not use the expression “iconic photograph,” it did call the photo “the indelible symbol of torture.” It might amount to the same thing.)

4

The picture was captioned “Ali Shalal Qaissi in Amman, Jordan, recently with the picture of himself standing atop a box and attached to electrical wires in Abu Ghraib.”

5

The story continues with a quote from Qaissi:

“I never wanted to be famous, especially not in this way,” he said, as he sat in a squalid office rented by his friends here in Amman. That said, he is now a prisoner advocate who clearly understands the power of the image: it appears on his business card.

At first glance, there is little to connect Mr. Qaissi with the infamous picture of a hooded man except his left hand, which he says was disfigured when an antique rifle exploded in his hands at a wedding several years ago. A disfigured hand also seems visible in the infamous picture, and features prominently in Mr. Qaissi’s outlook on life. In Abu Ghraib, the hand, with two swollen fingers, one of them partly blown off, and a deep gash in the palm, earned him the nickname “Clawman,” he said.

The Times hedged its bets and wrote, “A disfigured hand also seems visible . . .” It left open the possibility that what appeared to be a disfigured hand might be something else. The International Herald Tribune, however, was more definite. It said simply, “A disfigured hand shows up in the photograph.”

6

But it isn’t a disfigured hand, and Qaissi isn’t The Hooded Man.

7

The first questions arose two days later on Salon, when Michael Scherer presented army documents, photographs, and files “suggesting that the paper had identified the wrong man.”

8

In response to this and other criticism, the Times formally admitted the error in a March 18 article, and in an editors’ note that tried to explain how the mistake had been made:

The Times did not adequately research Mr. Qaissi’s insistence that he was the man in the photograph. Mr. Qaissi’s account had already been broadcast and printed by other outlets, including PBS and Vanity Fair, without challenge. Lawyers for former prisoners at Abu Ghraib vouched for him. Human rights workers seemed to support his account. The Pentagon, asked for verification, declined to confirm or deny it.

The Times’s public editor, Byron Calame, commented upon the error one week later, focusing on the reporters’ use of sources. The human rights workers cited in the story had never said they believed Qaissi was the man in the photograph, only that it was possible. Moreover, the article did not mention its reliance on the earlier stories, quietly taking their identification of Qaissi for the truth.

9

But there was one aspect of the controversy — the most crucial aspect — that was overlooked. No one acknowledged the central role that photography itself played in the mistaken identification, the way that photography lends itself to those errors and may even engender them.

10

I spoke to Hassan Fattah, author of the Times article that identified The Hooded Man. A graduate of the Columbia School of Journalism and correspondent for the Times in the Middle East, he was unusually honest and forthcoming in our discussion. I was impressed by the way he spoke about his attempts to verify Qaissi’s account. It was certainly not something he shrugged off. He called the week that the story was discredited the worst week in his career. It was a journalist’s worst nightmare.

11

HASSAN FATTAH: I basically was assigned the story. I was told to go see this guy who had been on Italian TV and had been interviewed several times elsewhere. I spent a few days trying to find him, actually. And he actually pulled out one or two times, and then finally was willing to meet me. I’m Iraqi myself, Iraqi-American. I worked in Iraq for a long time.

12

And I sat with him for a very, very long time and we talked. He’s a very compelling figure. You spoke to him, didn’t you?

13

ERROL MORRIS: Yes, but with difficulty. You would, of course, have had a much easier time.

14

HASSAN FATTAH: You spoke to him in English, obviously?

15

ERROL MORRIS: There was a translator. But we had trouble understanding each other. The poor phone connection, the constant stopping and starting for translation made conversation difficult. But he remembered Sabrina Harman [one of the MPs who guarded him at Abu Ghraib]. He told me that he liked her and asked if I could relay a message to her. He wanted her to speak on behalf of his organization. I wish I could have met him in person.

16

HASSAN FATTAH: I sat with him for a while because I just felt there was something too good about this story. But I kept in mind several things. First of all, he was able to describe the whole environment and everything that happened very, very accurately, in terms of how other people were describing it. He described the details of it and other aspects. It was very interesting that he knew the place so very well. He had a prisoner number, and he spoke about other prisoners that were there. He clearly had been in the prison, and we just needed to confirm that. And then I asked him, “Can you point yourself out in the picture?” And he got on his computer and he printed out the picture. And then we took his picture holding up that picture. And he said, “Here it is. Here’s my hand. Can you see it?” And then we looked at the picture, and the picture of the hand, and it looks very much like his hand. It turned out later that actually there is a high-resolution picture that came out that shows that it’s not his hand. I wish I had gotten that earlier. But that was the series of data points that our decision was based on.

17

ERROL MORRIS: So part of the problem was that the photograph was low-res and you couldn’t clearly see his deformed hand? That in some odd way, the photo was presented as definitive identification, but that Qaissi’s most distinguishing feature wasn’t visible?

18

HASSAN FATTAH: Yes. But he was able to describe the prison, the dynamics of the prison, and everything that was happening quite accurately. He had a very vivid memory of where the light fixtures were. The question was how do we really confirm his identity. I did talk first to Human Rights Watch, and then to Amnesty International. Human Rights Watch felt that yeah, this is the guy, we’ve known of him before, but they were a little tentative about it. So I talked to Amnesty and the guy — I forget his name, a German man who had spoken to him several times, in fact. He had referred to him on different issues about other prisoners and conditions in Abu Ghraib. So the Amnesty representative knew him well. He helped me go through the list of prisoners, and there he was on the list. That step proved he definitely was in Abu Ghraib, and we had the data for that. We have some of the pictures. And then he was quite convinced that he was the man. At least that’s how he said it. Of course, afterwards, he changed his story.

19

But it was ultimately Susan Burke [legal counsel acting on behalf of the Abu Ghraib torture victims] who sealed it for me. She went through the whole thing. They had the blanket, they had a lot of circumstantial evidence that linked Qaissi to the image. And she was very, very confident he was the one. The fact that they had the blanket was important to me. So we moved ahead with the story —

20

ERROL MORRIS: I’m sorry to interrupt, but when you said, “She had the blanket,” what does that mean? That she had the physical blanket?

21

HASSAN FATTAH: Yes, she had the physical blanket that he was wearing. They gave them blankets, and she walked me through this. Most of the time they were naked. And we know this; this is now on the record. And they gave them blankets at some point. And so they cut holes in the blankets and used them like ponchos. It ended up being a piece of clothing, and that’s what they slept with. Now, they had this poncho. And she felt that it was exactly the same poncho as the one in the picture.1 She had a bunch of other evidence that seemed to suggest this was true. And from there we went to the military and asked them to help us confirm his identity. At first they said, “Oh, yes, we’ve heard of him before, and we’ll get back to you.” And then the day afterwards — this is not to me, but to somebody who knows the military well, who did that reporting — they said, “We are not able to discuss this issue because it will violate his Geneva Convention rights.” So we ended up with all these different data points. And by the end I was convinced: this was the guy. His story was very accurate. It was also a very compelling story, but he wasn’t bitter about it. He was going to use this experience to help out some of the former prisoners. Obviously, the lawsuit that they [Human Rights Watch] have going is a big piece of the puzzle. This was going to be his way of getting some proper restitution. What is clear is that he was a man who was at Abu Ghraib, there’s no doubt about that. There was no reason for him to jeopardize this lawsuit. Why would he ruin it for himself by lying to the press? So we ran with the story. At some point we decided, okay, everything seems to stick.

22

ERROL MORRIS: And there had already been other news stories about him.

23

HASSAN FATTAH: Yes. There have been several profiles of him before in mainstream places. There was nothing that would suggest, after two years of this guy being out there, that this guy was not the man. There was nobody else who came up and said, “This was me.” There were court records. But because I didn’t cover the courts-martial I had not actually seen them. That proved to be the fatal flaw in my reporting. If I had to do it over again, if I’d seen the whole series of the latest photographs that had come out and had seen the courts-martial records first, and had ignored the fuzzy picture itself, I would have probably remained skeptical and would have held off for a lot longer. Probably I wouldn’t have done the story at all. More importantly, the more interesting story was the fact that these guys were around and were starting to talk to people. That there was the whole group of Abu Ghraib prisoners that had organized, and they were meeting with the lawyers the week that I was reporting the story.

24

ERROL MORRIS: Yes.

25

HASSAN FATTAH: And then we went to press, and the doubts about his identity came out. I called Qaissi and was talking to him, and it turned out that the lawyers were there with him, Susan Burke and her associates. Anyway, the lawyers were there with him, and they sought to convince me that he was telling the truth. Then it became apparent that they had nothing that could properly refute the allegations. And then he [Qaissi] finally admitted that the picture he printed out was not actually a picture of him. That’s when it was all over —

26

ERROL MORRIS: And who did he admit that to?

27

HASSAN FATTAH: He finally admitted it to me. He knew he was lying.

28

ERROL MORRIS: But wait. Is it clear that he knew he was lying?

29

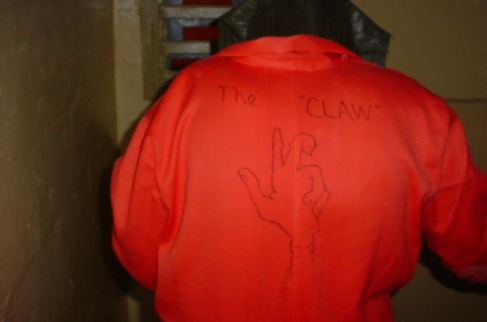

HASSAN FATTAH: Maybe not. He still insists he’s the real thing — and I’ve run into him several times since — and he continues to come to me and apologize, and continues to insist, “Please understand, I am in one of those pictures.” I personally believe there are many pictures, and he is probably the next guy in line. We do have some photographs in the same space, around the same time. We also have him with the blanket. We have seen him in other poses as well as the orange jumpsuit that he was wearing that said “Claw Man” on the back of it. There’s enough to suggest that he was in the space, he had been part of this, he had been involved and he had witnessed everything. But once he admitted that — “I am not the man in the photograph” — that was it. What more could I say? I realized I had been had. And then we had to do the retraction. What to me makes this especially a tragedy is that in many ways it detracted from his real story.

30

Susan Burke, the attorney who represents many of the torture victims, also suggested that it made no difference whether Qaissi, The Claw, was also really The Hooded Man — that his testimony is no less valid. This opinion was echoed by Donovan Webster, a Vanity Fair reporter, who argued that Ali Shalal Qaissi was doubtlessly subject to similar abuse:

As the reporter who first interviewed Qaissi — or as I called him, Haj Ali — for Vanity Fair, I was scrupulous to qualify that while he says the abuse happened to him (and his lawyer now has medical records to prove he was electrified), there might have been more than one person subjected to the same treatment, and we will likely never know unless someone else associated with the incident steps forward. During my months of reporting that story, I pushed to learn if there was more than one “hooded man on the box,” but, predictably, got nowhere with U.S. Army spokespeople, the Abu Ghraib soldiers present who were still available for comment, or several senators and congressmen working on a variety of Abu Ghraib investigations and commissions. Nonetheless, the army’s own records place Haj Ali on Tier 1A at the time of the Abu Ghraib abuses, and Haj Ali maintains that these abuses happened to him with the kinds of consistent, telling details that lead many to believe he is telling the truth. To discount the horrors visited upon this man because the famous photo shows a different detainee on the box — and to disbelieve what happened because no photo currently confirms it — well, it shows just how much of an abstraction torture has become inside American culture. Long to short: the issue is not about “individual interpretations of reality” or photographic imagery inspiring unearned lunges for international fame. It is about the idea at least two people might have been abused in a similar manner, but only one can produce a digital image to prove it.

I believe we are talking about two different things. The Claw was a prisoner at Abu Ghraib. He was most likely subjected to abuse, but whatever happened to him, whatever his account might be, it’s not the same as being the man in the picture.

31

And there is also the question of what Qaissi really believed, and what was going on inside his head. Had he also been hooded and put on a box with wires attached to him? In other words, was he a hooded man, but not The Hooded Man? If that was the case, he could have easily come to believe that he was The Hooded Man. If he truly believed that he was The Hooded Man, then he was innocent of conscious manipulation or misrepresentation.

32

But if The Claw was not The Hooded Man, and he knew it, why would he have made this false claim? Why would he have printed business cards with a drawing of The Hooded Man displayed next to his name? Did he see it as a business opportunity, as well as an opportunity to speak out against American policies in Iraq?

33

Human rights workers and prisoners needed a spokesperson to dramatize the growing evidence for abuses at Abu Ghraib and at other U.S. military prisons around the world. The Hooded Man was an ideal candidate — a living symbol of abuse. An icon. Susan Burke and Human Rights Watch had filed a class-action suit on behalf of Qaissi and several other named prisoners from Abu Ghraib. Qaissi had suffered at Abu Ghraib, and he had an interest in being heard. This is not to say that he or anyone else was involved in conscious fraud. But it is to say that there were pressures on everyone to believe that Qaissi was the man under the hood. For the lawyers, he was the centerpiece of litigation against torture at Abu Ghraib. For journalists, he presented the opportunity, on a date approaching the two-year anniversary of the release of the photographs, to tell the real story behind the most infamous among them. For the public, his story offered the allure of a solved mystery linked to a major scandal in American history.

34

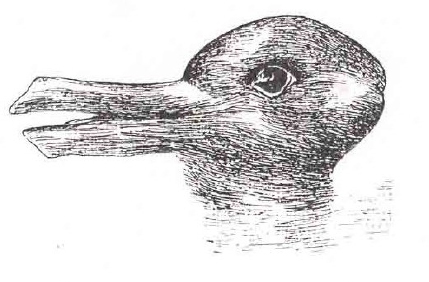

Years ago I became enamored with the writings of Norwood Russell Hanson, a philosopher and ex–fighter pilot who died at the age of forty-three while flying his own plane to a lecture engagement at Cornell. Long before Thomas Kuhn’s paradigms and Michael Polanyi’s tacit knowledge, Hanson pioneered the idea that observations in science are not independent of theory but are, on the contrary, quite dependent on it. In his book, Patterns of Discovery, published in 1958, Hanson coined the term “theory-laden” and wrote: “There is more to seeing than meets the eyeball.” Hanson had taken these ideas in part from Wittgenstein. In Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein uses a gestalt figure called the duck-rabbit, which can be seen either as a duck or a rabbit. The rabbit is facing right and the duck is facing left.2

35

To use the familiar gestalt image of the duck-rabbit: if we believe we see a rabbit, we see a rabbit. If we believe we see a duck, we see a duck. But the situation is even worse than the Gestalt psychologists imagined. Our beliefs can completely defeat sensory evidence. If we believe that we see The Claw in the photograph, then we see The Claw in the photograph, even though all we are looking at is a hooded man draped in a blanket, standing on a box, with only his legs and hands visible. The left hand might look disfigured, but the photograph has been taken with a low-resolution digital camera that provides limited evidence one way or the other. That we believe The Claw to be the man in the photograph does not mean he is the man in the photograph. Our beliefs do not determine what is true or false. They do not determine objective reality. But they can determine what we “see.”

36

There is yet another wrinkle to this. From this complex story about a photograph, its interpretation and reinterpretation, emerges another photograph and another story. The photograph of Qaissi holding the photograph of The Hooded Man. A photo of a photo. This photograph was the final piece of evidence in Qaissi’s claim to be The Hooded Man, even though it had no evidentiary value. Sadly, the new photograph for the Times also retained the same ambiguity, the same problematic lack of information, as the original photograph.

37

Take another look at the photograph that appeared in the Times. The Claw is seen standing holding the iconic photograph, but only his right hand is visible. His left hand is framed out of the photograph. His deformed hand is hidden. Intentionally? Unintentionally?

38

The Times photographer who took the shot could have helped me sort through these possibilities, but he declined to be interviewed, insisting when I reached him by phone in Cairo that the photograph was a “false” photograph and that he didn’t want to discuss it. I tried to reassure him. There was nothing false about the photograph. The photograph is simply a photograph of Qaissi holding a photograph of The Hooded Man, which is neither true nor false. “Yes,” I told him, “there was something false about Qaissi’s claim that he was the man under the hood, but the photograph itself is not making that claim. The photograph is just a photograph.”

39

I asked Hassan what he remembered about the photo shoot.

HASSAN FATTAH: Although we took frames of his hand. Qaissi had sought to keep his hand out of the frame in this photo, as I remember it. It was as if he had the image and the shot already orchestrated in his mind.

40

Was there a conscious decision made to crop the photograph, or to frame the image in such a way as to leave out the left hand? Or was it something subtler, possibly intangible? Presumably, many photographs were taken, and this photograph was chosen because the image is more powerful, more mysterious, without the hand. Quite often photographs gain power from what is omitted from the frame rather than from what is included. This one leaves the question of what Qaissi’s “claw” might look like open to the imagination.

41

But framing out the left hand from the photo merely aids and abets the mystery. As such, the photograph should be a constant reminder — not of how photographs can be true or false — but of how we can make false inferences from a photograph. Photography presents things and at the same time hides things from our view, and the coupling of photography and language provides an express train to error.

42

The nickname is part of the problem. Like many of the names given to prisoners at Abu Ghraib by the MPs who guarded them, “The Claw” recalls characters from American popular culture — comic books, television, movies. The name conjures up an image of a seriously deformed hand — a pincer or worse. And because we have no picture of the claw itself, we are free to imagine anything from a broken finger that didn’t heal properly to a horribly disfigured, well, claw. These imaginings are based on seeing nothing and imagining everything.

43

When my friend Charles Silver finally saw the photograph below of Qaissi’s actual hand, he was disappointed. He felt it wasn’t really a claw, and that he had been misled. He suggested that The Claw’s hand was not shown in the original article because readers might have concluded that he was an impostor, based on the comparative normalcy of the hand.

44

Qaissi was given the nickname by Hydrue Joyner, the staff sergeant who supervised the day shift that guarded prisoners on Tier 1A at Abu Ghraib.

45

I spoke with Sgt. Joyner about The Claw:

ERROL MORRIS: And The Claw? How did he get his name?

HYDRUE JOYNER: The Claw? Dr. Claw. Oh, yeah, Dr. Claw. I don’t know if you ever saw that movie, Scary Movie: Part 2, where the guy had the hand and everything? He had a hand just like that. I couldn’t think of anything else but Dr. Claw. That wasn’t my fault. I work with the material that I have, and he just provided material for me, so that’s how he ended up with the name “Dr. Claw.”

ERROL MORRIS: Are you the one responsible for naming all these people?

HYDRUE JOYNER: Yes, it’s my fault. I named all of them. And it came to a point where because of the nicknames I gave them, we were able to identify them a lot easier than Detainee #67328. It got to a point where I would call them by their nickname and they would answer, “Yes, here.” So it became a popular thing. The detainees liked it. I tried to make it somewhat entertaining. It was still jail but you can still laugh in jail. It’s not a crime, I hope.

46

Sergeant Joyner also had a nickname for Detainee #18470, whose real name was Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh. He called him “Gilligan” because he was so skinny. (I continue to use the nicknames — The Claw and Gilligan — not out of disrespect for the prisoners involved but because the nickname is an essential part of the story of misidentification.) Gilligan is the real Hooded Man.

47

While working on Standard Operating Procedure, a film about the infamous photographs of Abu Ghraib, I interviewed many of the MPs who were involved. Principal among them was Sabrina Harman, who had taken some of the Hooded Man photographs. Sabrina offered considerable evidence that Gilligan was the real Hooded Man.

48

Sabrina remembers both The Claw and Gilligan vividly. She photographed both of them on the same night. Gilligan, as his name implies, was slight of build. The Claw was heavyset. There was no doubt in Sabrina’s mind. “Gilligan was on the box,” she told me, “not The Claw.” The Claw was her prisoner, and he was not put on a box, nor attached to wires. According to Sabrina, “The Claw weighed over three hundred pounds. If The Claw had been put on an MRE [Meals Ready to Eat] box, he would have crushed it.” For me this is one of those telling little details that give her account the ring of truth.

49

But both The Claw and Gilligan were interrogated in the same area of Abu Ghraib, Tier 1A, on the night that the Hooded Man photographs were taken. Salon reported on an e-mail from Qaissi: “I have seen at least two pictures showing this dreadful experience. . . . One is me. The other I believe could be Saad because he went before me to the area I had to go, where I was to be interrogated.”

50

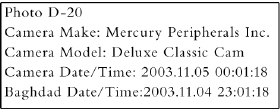

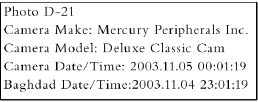

There are multiple photographs taken on November 3, 2003, on Tier 1A, Abu Ghraib — the night of the Hooded Man photograph. Both Salon and I had copies of these photographs, which were collected by the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the U.S. Army for use in the varied courts-martial related to the Abu Ghraib abuse photographs. I don’t believe the Times had a copy prior to the publication of its story.

51

In the photograph below, you can clearly see that The Claw is fully clothed in an orange jumpsuit, which has been labeled on the back in black Magic Marker “The Claw” above a crude caricature of a deformed hand. He is shown to be stocky and made to kneel on the floor, not stand on a box. The detail photograph of his hand was taken the same night as he was apparently made to proffer it.

52

Gilligan, by contrast, is hooded and wearing only a black blanket or poncho. He’s photographed from different angles and by different cameras. There are two (virtually identical) “iconic” photographs of The Hooded Man taken within one second of each other by Sergeant Ivan Frederick with a Deluxe Classic Cam.3 Both of these photographs are comparatively low-resolution: 640 × 480 (0.3 megapixels) and were taken without a flash. (Since they are virtually identical — the second one seems to be only slightly panned to the right — I will write about them as essentially one photograph.)

53

And then there is a wide-angle shot of Gilligan on the box taken by Sabrina Harman. Sergeant Ivan Frederick, who took the two previous pictures, is standing on the right side of the frame. This photograph was taken approximately three minutes later with the FD Mavica, which has a much higher resolution: 1280 × 1600 (2.0 megapixels, more than six times the resolution of the iconic photographs), and was taken with a flash.

54

For me, it is by far the more interesting photograph. It shows Frederick looking at the picture he has just taken — a picture that was destined to become a photograph seen around the world. What is he thinking? It is unlikely that he imagined this image printed in newspapers and displayed on computer screens everywhere. We are looking at the photograph of Frederick looking at his photograph of The Hooded Man with The Hooded Man in the background.

55

Such a photograph would have been impossible during World War II, when professional photographers like Joe Rosenthal were covering the war. Rosenthal never even saw his photo of the flag raising at Iwo Jima until it made the papers. The Hooded Man is a radically modern image, insofar as it shows someone looking at an image instantaneously displayed on a digital camera screen while the “reality” behind that image is seen clearly next to him.

56

I have often wondered why it was Frederick’s photograph, and not Sabrina Harman’s photograph, that became iconic. (It is even possible to create a facsimile of Frederick’s photograph by cropping Harman’s, save that Frederick’s is in portrait mode and Harman’s in landscape mode, and there is more “room” under the box in Frederick’s photograph. Also, there is a soft shadow behind The Hooded Man in Frederick’s photo, a hard shadow behind Frederick in Harman’s photo.) My belief is that Harman’s photograph is more complicated and requires context. Who is that man standing on the right of the frame? He seems disengaged. What is he doing? When I interviewed Lieutenant Colonel Steve Jordan,4 who was the director of the Joint Interrogation and Debriefing Center (JIDC) at Abu Ghraib, he described the picture to me as a picture of Sergeant Frederick clipping his nails. It was only after I explained to him that Frederick was looking at the photograph he had just taken that Jordan realized he had misinterpreted what he was looking at. It makes a big difference. In one version Frederick is indifferent to the scene next to him; in the other, he is contemplating his image of it — an image that he saw the need to record and preserve.

57

Frederick’s picture — the one that became iconic — has no one else in the frame. It is stripped of context, like the gestalt duck-rabbit, ambiguous and open to interpretation.

58

Photographs attract false beliefs the way flypaper attracts flies. Why my skepticism? Because vision is privileged in our society and our sensorium. We trust it; we place our confidence in it. Photography allows us to uncritically think. We imagine that photographs provide a magic path to the truth.

59

What’s more, photographs allow us to think we know more than we really do. We can imagine a context that isn’t really there. In the pre-photographic era, images came directly from our eyes to our brains and were part of our experience of reality. With the advent of photography, images were torn free from the world, snatched from the fabric of reality, and enshrined as separate entities. They became more like dreams. It is no wonder that we really don’t know how to deal with them.

60

The New York Times’s public editor, in his March 26, 2006, article about the misidentification, suggested that lack of research was the problem.

61

He focused on the evidence in the archives of his own paper:

Embarrassingly, evidence to prevent the whole mess was in The Times’s archives. In an article on May 22, 2004, the paper had correctly identified the man in the photograph as Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh. Ethan Bronner, deputy foreign editor, wrote to me in an e-mail that editors had done several searches of the paper’s archives using various keywords. He said editors now realize that one search — using the terms “Abu Ghraib,” “box” and “hood” — missed the crucial May 2004 article because it didn’t contain the word “hood.”

My test of the same three search words last week, however, turned up two Times articles from last year reporting that the man in the famous photograph had been called “Gilligan” by guards at Abu Ghraib. Mr. Qaissi, according to the March 11 story, had been nicknamed “Clawman.” The contradictory nicknames, it seems to me, should have spurred more intensive search efforts and raised an overall caution flag.

Mr. Bronner disputes the value of the two stories with “Gilligan” references. He said editors had come across at least one of them in their searches, but hadn’t considered it significant. Among other things, he said, it wasn’t clear then that Mr. Qaissi had only one nickname.

The detail about the extra search term “hood” obscuring “the crucial May 2004 article” is telling. It wasn’t that the article was overlooked. Bronner says they saw the “Gilligan” reference but “hadn’t considered it significant.” I would suggest it was because Bronner already believed that the photo of Qaissi was The Hooded Man. And so he turned to a clunky, speculation-laden theory — that The Hooded Man was called both “Clawman” (or “The Claw”) and “Gilligan” — rather than questioning his belief in Qaissi’s story.5

62

But the failure to look at certain kinds of evidence may be explained by the belief that a proof had already been offered, that there was already enough evidence to make the case. Yes, there was archival material that could have cast suspicion on the claim that The Claw was also The Hooded Man. But the mistaken identification was driven by The Claw’s own desire to be the iconic victim, to be The Hooded Man, and our own need to believe him. It is an error engendered by photography and perpetuated by us. And it comes from a desire for “the ocular proof,” a proof that turns out to be no proof at all. What we see is not independent of our beliefs. Photographs provide evidence, but no shortcut to reality. It is often said that seeing is believing. But we do not form our beliefs on the basis of what we see; rather, what we see is often determined by our beliefs. Believing is seeing, not the other way around.

63

When the Times identified The Hooded Man, it provided the solution to a mystery — a who-is-under-it, rather than a whodunnit. But the Times piece also allayed our fears and perhaps assuaged our collective guilt about what happened to The Hooded Man. Perhaps there was a collective sigh of relief when we learned that he survived. Perhaps there was a sense that we could put all this behind us. The Hooded Man served a need.

64

But if The Claw isn’t The Hooded Man, the mystery reopens and the guilt and the horror resume. If The Claw isn’t The Hooded Man, we have to face again what the American military did to prisoners in their custody. If The Claw isn’t The Hooded Man, whose account are we listening to?6

65

Gilligan was interviewed by CID on January 16, 2004, shortly after the investigations into prisoner abuse began. His unsigned statement was translated and later included in the report issued by the Taguba Commission, the military body formed after abuse charges surfaced to investigate detention and internment operations at Abu Ghraib.7 The report did not include a statement by Detainee #151716 (Qaissi, a.k.a. The Claw) nor was I able to find one elsewhere. This is Gilligan’s statement as it appears in the report issued by the commission:

TRANSLATION OF STATEMENT PROVIDED BY Abdou Hussain Saad Falah, Detainee #18470, 1610/16 JAN 04:

On the third day, after five o’clock, Mr. Grainer [sic] came and took me to Room #37, which is the shower room, and he started punishing me. Then he brought a box of food and he made me stand on it with no clothing, except a blanket. Then a tall black soldier came and put electrical wires on my fingers and toes and on my penis, and I had a bag over my head. Then he was saying “which switch is on for electricity.” And he came with a loudspeaker and he was shouting near my ear and then he brought the camera and he took some pictures of me, which I knew because of the flash of the camera. And he took the hood off and he was describing some poses he wanted me to do, and I was tired and I fell down. And then Mr. Grainer [sic] came and made me stand up on the stairs and made me carry a box of food. I was so tired and I dropped it. He started screaming at me in English. He made me lift a white chair high in the air. Then the chair came down and then Mr. Joyner took the hood off my head and took me to my room. And I slept after that for about an hour and then I woke up at the headcount time. I couldn’t go to sleep after that because I was very scared.

This statement is an important reminder that there was a person under that hood and that something horrible happened to him. The photograph of Faleh should not be viewed as just some image devoid of context to be taken up by any abused prisoner. It is important to remember that Faleh’s existence continues outside the frame of the photograph. He is a real person.

66

My staff and I spent a good part of a year trying to find Faleh. He had disappeared without a trace. All that remains is his statement to CID and this photograph of a single, seemingly anonymous hooded figure. The photograph of The Hooded Man has created its own iconography and its own narrative. It has become the iconic image of the Iraq War in the West. But, as Hassan Fattah pointed out to me, “You have to realize that what we in the West think is the iconic image of Abu Ghraib, it’s the man on the box. But, actually in the Arab world, in the Muslim world, the iconic image is actually her smiling next to the dead body.” Hassan Fattah is referring to the photograph of Sabrina Harman smiling and giving the thumbs-up over the body of a dead detainee. It is not surprising that the Muslim world should have a different iconic photograph of the war in Iraq. Nor is it surprising that the image is an even more potent symbol of abuse and victimization.