EDWARD SAID

EDWARD

SAID

Edward Said (1935–2003) was one of the world’s most distinguished literary critics and scholars, distinguished (among other things) for his insistence on the connectedness of art and politics, literature and history. As he argues in his influential essay “The World, the Text, the Critic,”

Texts have ways of existing, both theoretical and practical, that even in their most rarefied form are always enmeshed in circumstance, time, place, and society — in short, they are in the world, and hence worldly. The same is doubtless true of the critic, as reader and as writer.

Said (pronounced “sigh-eed”) was a “worldly” reader and writer, and the selection that follows is a case in point. It is part of his long-term engagement with the history and politics of the Middle East, particularly of the people we refer to as Palestinians. His critical efforts, perhaps best represented by his most influential book, Orientalism (1978), examine the ways the West has represented and understood the East (“They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented”), demonstrating how Western journalists, writers, artists, and scholars have created and preserved a view of Eastern cultures as mysterious, dangerous, unchanging, and inferior.

Said was born in Jerusalem, in what was at that time Palestine, to parents who were members of the Christian Palestinian community. In 1947, as the United Nations was establishing Israel as a Jewish state, his family fled to Cairo. In the introduction to After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives (1986), the book from which the following selection was taken, he says,

I was twelve, with the limited awareness and memory of a relatively sheltered boy. By the mid-spring of 1948 my extended family in its entirety had departed, evicted from Palestine along with almost a million other Palestinians. This was the nakba, or catastrophe, which heralded the destruction of our society and our dispossession as a people.

Said was educated in English-speaking schools in Cairo and Massachusetts; he completed his undergraduate training at Princeton and received his PhD from Harvard in 1964. He was a member of the English department at Columbia University in New York from 1963 until his death from leukemia. In the 1970s, he began writing to a broad public on the situation of the Palestinians; from 1977 to 1991, he served on the Palestinian National Council, an exile government. In 1991, he split from the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) over its Gulf War policy (Yasir Arafat’s support of Saddam Hussein) and, as he says, for “what I considered to be its new defeatism.”

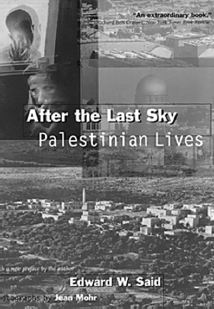

The peculiar and distinctive project represented by After the Last Sky began in the 1980s, in the midst of this political engagement. “In 1983,” Said writes in the introduction,

while I was serving as a consultant to the United Nations for its International Conference on the Question of Palestine (ICQP), I suggested that photographs of Palestinians be hung in the entrance hall to the main conference site in Geneva. I had of course known and admired Mohr’s work with John Berger, and I recommended that he be commissioned to photograph some of the principal locales of Palestinian life. Given the initial enthusiasm for the idea, Mohr left on a special UN-sponsored trip to the Near East. The photographs he brought back were indeed wonderful; the official response, however, was puzzling and, to someone with a taste for irony, exquisite. You can hang them up, we were told, but no writing can be displayed with them.

In response to a UN mandate, Said had also commissioned twenty studies for the participants at the conference. Of the twenty, only three were accepted as “official documents.” The others were rejected “because one after another Arab state objected to this or that principle, this or that insinuation, this or that putative injury to its sovereignty.” And yet, Said argues, the complex experience, history, and identity of the people known as Palestinians remained virtually unknown, particularly in the West (and in the United States). To most, Said says, “Palestinians are visible principally as fighters, terrorists, and lawless pariahs.” When Jean Mohr, the photographer, told a friend that he was preparing an exhibition on the Palestinians, the friend responded, “Don’t you think the subject’s a bit dated? Look, I’ve taken photographs of Palestinians too, especially in the refugee camps . . . it’s really sad! But these days, who’s interested in people who eat off the ground with their hands? And then there’s all that terrorism. . . . I’d have thought you’d be better off using your energy and capabilities on something more worthwhile.”

For both Said and Mohr, these rejections provided the motive for After the Last Sky. Said’s account, from the book’s introduction, is worth quoting at length for how well it represents the problems of writing:

Let us use photographs and a text, we said to each other, to say something that hasn’t been said about Palestinians. Yet the problem of writing about and representing — in all senses of the word — Palestinians in some fresh way is part of a much larger problem. For it is not as if no one speaks about or portrays the Palestinians. The difficulty is that everyone, including the Palestinians themselves, speaks a very great deal. A huge body of literature has grown up, most of it polemical, accusatory, denunciatory. At this point, no one writing about Palestine — and indeed, no one going to Palestine — starts from scratch: We have all been there before, whether by reading about it, experiencing its millennial presence and power, or actually living there for periods of time. It is a terribly crowded place, almost too crowded for what it is asked to be by way of history or interpretation of history.

The resulting book is quite a remarkable document. The photos are not the photos of a glossy coffee-table book, and yet they are compelling and memorable. The prose at times leads to the photos; at times it follows as meditation or explanation, an effort to get things right — “things like exile, dispossession, habits of expression, internal and external landscapes, stubbornness, poignancy, and heroism.” It is a writing with pictures, not a writing to which photos were later added. Said had, in fact, been unable to return to Israel/Palestine for several years. As part of this project, he had hoped to be able to take a trip to the West Bank and Gaza in order to see beyond Mohr’s photographs, but such a trip proved to be unsafe and impossible — both Arab and Israeli officials had reason to treat him with suspicion. The book was written in exile; the photos, memories, books, and newspapers, these were the only vehicles of return.

After the Last Sky is, Said wrote in 1999, “an unreconciled book, in which the contradictions and antinomies of our lives and experiences remain as they are, assembled neither (I hope) into neat wholes nor into sentimental ruminations about the past. Fragments, memories, disjointed scenes, intimate particulars.” The Palestinians, Said wrote in the introduction, fall between classifications. “We are at once too recently formed and too variously experienced to be a population of articulate exiles with a completely systematic vision and too voluble and trouble making to be simply a pathetic mass of refugees.” And he adds, “The whole point of this book is to engage this difficulty, to deny the habitually simple, even harmful representations of Palestinians, and to replace them with something more capable of capturing the complex reality of their experience.”

Furthermore, he says, “just as Jean Mohr and I, a Swiss and a Palestinian, collaborated in the process, we would like you — Palestinians, Europeans, Americans, Africans, Latin Americans, Asians — to do so also.” This is both an invitation and a challenge. While there is much to learn about the Palestinians, the people and their history, the opening moment in the collaborative project is to learn to look and to read in the service of a complex and nuanced act of understanding.

Said is the author of many books and collections, including Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography (1966), Beginnings: Intention and Method (1975), Orientalism (1978), The Question of Palestine (1979), Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (1981), Blaming the Victims (1988), Musical Elaborations (1991), Culture and Imperialism (1993), The Politics of Dispossession: The Struggle for Palestinian Self-Determination, 1989–1994 (1994), Representations of the Intellectual (1994), Peace and Its Discontents: Essays on Palestine in the Middle East Peace Process (1995), Out of Place: A Memoir (2000), Reflections on Exile (2000), The Edward Said Reader (2000), The End of the Peace Process: Oslo and After (2001), Power, Politics, and Culture (2001), Mona Hatoum: The Entire World as a Foreign Land (2001), On Late Style:Music and Literature Against the Grain (2006), and Music at the Limits (2007).

Jean Mohr has worked as a photographer for UNESCO, the World Health Organization, and the International Red Cross. He has collaborated on four books with John Berger: Ways of Seeing (1972; see excerpt on p. 000), A Seventh Man (1975), Another Way of Telling (1982), and A Fortunate Man (1967).