Chicago-style research project (Amanda Rinder)

"Sweet Home Chicago: Preserving the Past, Protecting the Future of the Windy City" is a researched argument written for a history class in which Amanda Rinder discusses the preservation of Chicago's architecture. The project follows the guidelines of Chicago style.

Rinder 1

Sweet Home Chicago: Preserving the Past,

Protecting the Future of the Windy City

Amanda Rinder

Twentieth-Century U.S. History

Professor Goldberg

November 27, 2006

Rinder 2

Only one city has the “Big Shoulders” described by Carl Sandburg: Chicago (fig. 1). So renowned are its skyscrapers and celebrated building style that an entire school of architecture is named for Chicago. Presently, however, the place that Frank Sinatra called “my kind of town” is beginning to lose sight of exactly what kind of town it is. Many of the buildings that give Chicago its distinctive character are being torn down in order to make room for new growth. Both preserving the classics and encouraging new creation are important; the combination of these elements gives Chicago architecture its unique flavor. Witold Rybczynski, a professor of urbanism at the University of Pennsylvania, told the New York Times, “Of all the cities we can think of … we associate Chicago with new things, with building new. Combining that with preservation is a difficult task, a tricky thing. It’s hard to find the middle ground in Chicago.”1 Yet finding a middle ground is essential if the city is to retain the original character that sets it apart from the rest. In order to maintain Chicago’s distinctive identity and its delicate balance between the old and the new, the city government must provide a comprehensive urban plan that not only directs growth, but calls for the preservation of landmarks and historic districts as well.

Chicago is a city for the working man. Nowhere is this more evident than in its architecture. David Garrard Lowe, author of Lost Chicago, notes that early Chicagoans “sought reality, not fantasy, and the reality of America as seen from the heartland did not include the pavilions of princes or the castles of kings.”2 The inclination toward unadorned, sturdy buildings began in the late nineteenth century with the aptly named Chicago School, a movement led by Louis Sullivan, John Wellborn Root, and Daniel Burnham and based on Sullivan’s adage, “Form follows function.”3 The early skyscraper, the very symbol of the Chicago style, represents the triumph of function and utility over sentiment, America over Europe, and perhaps even the frontier over the civilization of the east coast.4 These ideals of the original Chicago School were expanded upon by architects of the Second Chicago School. Frank Lloyd Wright’s legendary organic style and the famed glass and steel constructions of Mies van der Rohe are often the first images that spring to mind when one thinks of Chicago.

Yet the architecture that is the city’s defining attribute is being threatened by the increasing tendency toward development. The root of Chicago’s preservation problem lies in the enormous drive toward economic expansion and the potential in Chicago for such growth. The highly competitive market for land in the city means that properties sell for the highest price if the buildings on them can be obliterated to make room for newer, larger developments. Because of this preference on the part of potential buyers, the label “landmark” has become a stigma for property owners. “In other cities, landmark status is sought after—in Chicago, it’s avoided at all costs,” notes Alan J. Shannon of the Chicago Tribune.5 Even if owners wish to keep their property’s original structure, designation as a landmark is still undesirable as it limits the renovations that can be made to a building and thus decreases its value. Essentially, no building that has even been recommended for landmark status may be touched without the approval of the Commission on Chicago Historical and Architectural Landmarks, a restriction that considerably diminishes the appeal of the real estate. “We live in a world where the owners say, ‘If you judge my property a landmark you are taking money away from me.’ And in Chicago the process is stacked in favor of the economics,” says former city Planning Commissioner David Mosena.6

Rinder 4

Nowhere is this clash more apparent than on North Michigan Avenue—Chicago’s Magnificent Mile. The historic buildings along this block are unquestionably some of the city’s finest works. In addition, the Mile is one of Chicago’s most prosperous districts. The small-scale, charming buildings envisioned by Arthur Rubloff, the real estate developer who first conceived of the Magnificent Mile in the late 1940s, could not accommodate the crowds. Numerous high-rises, constructed to accommodate the masses that flock to Michigan Avenue, interrupt the cohesion and unity envisioned by the original planners of the Magnificent Mile. In Chicago’s North Michigan Avenue, John W. Stamper says that with the standard height for new buildings on the avenue currently at about sixty-five stories, the “pleasant shopping promenade” has become a “canyon-like corridor.”7

Many agree that the individual style of Michigan Avenue is being lost. In 1995, the same year that the Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois declared the section of Michigan Avenue from Oak Street to Roosevelt Road one of the state’s ten most endangered historic sites, the annual sales of the Magnificent Mile ran around $1 billion and were increasing at an annual rate of about five to seven percent.8 Clearly, the property’s potential as part of a commercial hub is taking priority over its architectural and historic value. The future of this district rests on a precarious balance between Chicago’s responsibility for its own heritage and Chicagoans’ desire for economic gain.

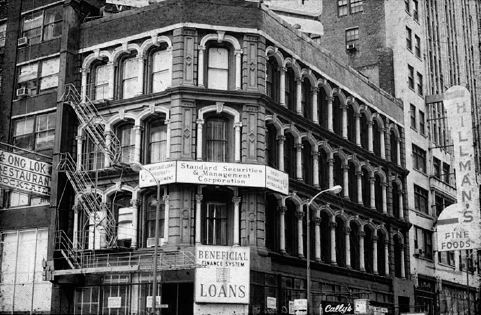

Perhaps the best single example of the conflict between preservation and development in Chicago is the case of the McCarthy Building (fig. 2). Built in 1872, the McCarthy was designed by John M. Van Osdel, Chicago’s first professional architect. Paul Gapp, a Chicago Tribune architecture critic, described it as “a stunningly appealing relic from Chicago’s 19th century Renaissance era.”9 The McCarthy was made a landmark in 1984, but it wasn’t long before developers recognized the potential of the property, situated on Block 37 of State Street, directly across from Marshall Field’s. With plans for a $300 million retail and office complex already outlined, developers made a $12.3 million bid for the property, promising to preserve the McCarthy and integrate it into the complex. The city readily agreed. However, a series of modifications over the next two years completely transformed the original plan. With the old structure now useless to the project, developers made subsequent proposals to preserve just the facade, or even to move the entire McCarthy Building to another location. When these propositions didn’t work out, the developers began offering to preserve other buildings in exchange for permission to demolish the McCarthy. Gapp admitted that the city was caught in a difficult situation: if it protected the McCarthy, it would be impeding development in an important urban renewal area, and if it allowed demolition, Chicago’s landmark protection ordinance would be completely devalued. He nonetheless urged city officials to choose the “long view” and preserve the McCarthy.10 However, the developers’ offer to buy and restore the Reliance Building, at a cost of between $7 million and $11 million, and to contribute $4 million to other preservation efforts, prevailed. In September 1987, the Chicago City Council voted to revoke the McCarthy’s landmark status.

Rinder 5

Ironically, Chicago’s rich architectural heritage may work against its own preservation. With so many significant buildings, losing one does not seem as critical as perhaps it should. The fact that Chicago boasts some forty-five Mies buildings, seventy-five Frank Lloyd Wright buildings, and numerous other buildings from the first and second Chicago Schools may inspire a nonchalant attitude toward preservation.11

Rinder 6

The razing of the McCarthy Building in 1987 exposes the problems inherent in Chicago’s landmark policy. But the real tragedy is that none of the plans for development of the property were ever carried out. Block 37 remains vacant to this day. Clearly, the city needs creative and vigilant urban planning.

To uphold Chicago’s reputation as an architectural jewel, the city must manage development by easing the economic burdens that preservation entails. Some methods that have been suggested for this are property tax breaks for landmark owners and transferable development rights, which would give landmark owners bonuses for developing elsewhere. Overall, however, the city’s planning and landmarks commissions simply need to become more involved, working closely with developers throughout the entire design process.

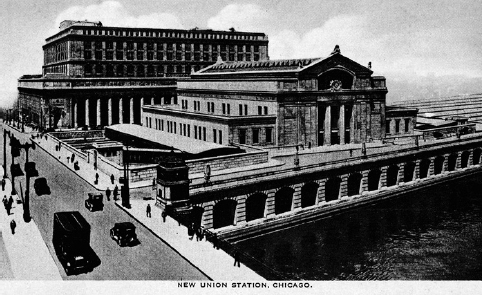

The effectiveness of an earnest but open-minded approach to urban planning has already been proven in Chicago. Union Station (fig. 3) is one project that worked to the satisfaction of both developers and preservationists. Developers U.S. Equities Realty Inc. and Amtrak proposed replacing the four floors of outdated office space above the station with more practical high-rise towers. This offer allowed for the preservation of the Great Hall and other public spaces within the station itself. “We are preserving the best of the historical landmark … and at the same time creating an adaptive reuse that will bring back some of the old glory of the station,” Cheryl Stein of U.S. Equities told the Tribune.12 The city responded to this magnanimous offer in kind, upgrading zoning on the site to permit additional office space and working with developers to identify exactly which portions of the original structure needed to be preserved. Today, the sight of Union Station, revitalized and bustling, is proof of the sincere endeavors of developers and city planners alike.

Rinder 7

In the midst of abandonment and demolition, buildings such as Union Station and the Reliance Building offer Chicago some hope for a future that is as architecturally rich as its past. The key to achieving this balance of preserving historic treasures and encouraging new development is to view the city not so much as a product, but as a process. Robert Bruegmann, author of The Architects and the City, defines a city as “the ultimate human artifact, our most complex and prodigious social creation, and the most tangible result of the actions over time of all its citizens.”13 Nowhere is this sentiment more relevant than in Chicago. Comprehensive urban planning will ensure that the city’s character, so closely tied to its architecture, is preserved.

Rinder 8

Notes

1. Tracie Rozhon, “Chicago Girds for Big Battle over Its Skyline,” New York Times, November 12, 2000, Academic Search Premier.

2. David Garrard Lowe, Lost Chicago (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2000), 123.

3. Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. (2000), s.v. “Louis Sullivan.”

4. Daniel Bluestone, Constructing Chicago (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), 105.

5. Alan J. Shannon, “When Will It End?” Chicago Tribune, September 11, 1987, quoted in Karen J. Dilibert, From Landmark to Landfill (Chicago: Chicago Architectural Foundation, 2000), 11.

6. Steve Kerch, “Landmark Decisions,” Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1990, sec. 16.

7. John W. Stamper, Chicago’s North Michigan Avenue (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 215.

8. Alf Siewers, “Success Spoiling the Magnificent Mile?” Chicago Sun-Times, April 9, 1995.

9. Paul Gapp, “McCarthy Building Puts Landmark Law on a Collision Course with Developers,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1986, quoted in Karen J. Dilibert, From Landmark to Landfill (Chicago: Chicago Architectural Foundation, 2000), 4.

10. Gapp, qtd. in Dilibert, 4.

11. Rozhon, “Chicago Girds for Big Battle.”

12. Kerch, “Landmark Decisions.”

13. Robert Bruegmann, The Architects and the City (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 443.

Rinder 9

Bibliography

Bluestone, Daniel. Constructing Chicago. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

Bruegmann, Robert. The Architects and the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Dilibert, Karen J. From Landmark to Landfill. Chicago: Chicago Architectural Foundation, 2000.

Kerch, Steve. “Landmark Decisions.” Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1990, sec. 16.

Lowe, David Garrard. Lost Chicago. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2000.

Rozhon, Tracie. “Chicago Girds for Big Battle over Its Skyline.” New York Times, November 12, 2000. Academic Search Premier.

Siewers, Alf. “Success Spoiling the Magnificent Mile?” Chicago Sun-Times, April 9, 1995.

Stamper, John W. Chicago’s North Michigan Avenue. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.