Distinguishing main ideas

Page contents:

Subordination allows you to distinguish major points from minor points or to bring supporting details into a sentence. If, for instance, you put your main idea in an independent clause, you might then put any less significant ideas in dependent clauses, phrases, or even single words. The following sentence highlights the subordinated point:

Mrs. Viola Cullinan was a plump woman who lived in a three-

—MAYA ANGELOU, “My Name Is Margaret”

The dependent clause adds important information about Mrs. Cullinan, but it is subordinate to the independent clause.

Notice that the choice of what to subordinate rests with the writer and depends on the intended meaning. Angelou might have given the same basic information differently:

Mrs. Viola Cullinan, a plump woman, lived in a three-

Subordinating the information about Mrs. Cullinan’s size to that about her house would suggest a slightly different meaning, of course. As a writer, you must think carefully about what you want to emphasize and must subordinate information accordingly.

Subordination also establishes logical relationships among different ideas. These relationships are often specified by subordinating conjunctions.

SOME COMMON SUBORDINATING CONJUNCTIONS

| after | if | though |

| although | in order that | unless |

| as | once | until |

| as if | since | when |

| because | so that | where |

| before | than | while |

| even though | that |

The following sentence highlights the subordinate clause and italicizes the subordinating word:

She usually rested her smile until late afternoon when her women friends dropped in and Miss Glory, the cook, served them cold drinks on the closed-

—MAYA ANGELOU, “My Name Is Margaret”

Using too many coordinate structures can be monotonous and can make it hard for readers to recognize the most important ideas. Subordinating lesser ideas can help highlight the main ideas.

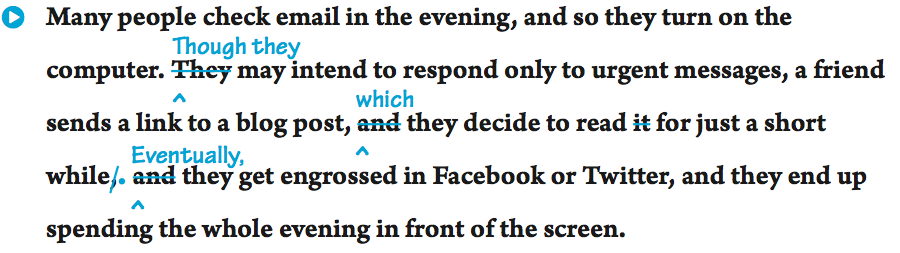

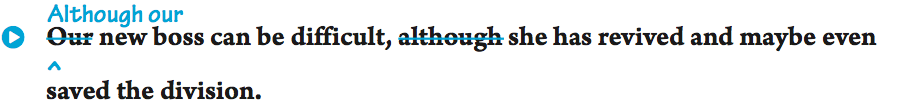

Subordination for less important information

The editing puts the more important information—

Excessive subordination

When too many subordinate clauses are strung together, readers may have trouble keeping track of the main idea expressed in the independent clause.

TOO MUCH SUBORDINATION

Philip II sent the Spanish Armada to conquer England, which was ruled by Elizabeth, who had executed Mary because she was plotting to overthrow Elizabeth, who was a Protestant, whereas Mary and Philip were Roman Catholics.

REVISED

Philip II sent the Spanish Armada to conquer England, which was ruled by Elizabeth, a Protestant. She had executed Mary, a Roman Catholic like Philip, because Mary was plotting to overthrow her.

Putting the facts about Elizabeth executing Mary into an independent clause makes key information easier to recognize.

You can employ a variety of grammatical structures—

The parks report was persuasively written. It contained five typed pages. [no subordination]

The parks report, which contained five typed pages, was persuasively written. [dependent clause]

The parks report, containing five typed pages, was persuasively written. [participial phrase]

The five-

The parks report, five typed pages, was persuasively written. [appositive]

The parks report, its five pages neatly typed, was persuasively written. [absolute]

Subordination for special effect

Some particularly fine examples of subordination come from Martin Luther King Jr. In the following passage, he piles up dependent clauses beginning with when to build up suspense for his main statement, given in the independent clause at the end:

Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-

—MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., “Letter from Birmingham Jail”

A dependent clause can also create an ironic effect if it somehow undercuts the independent clause. A master of this technique, Mark Twain once opened a paragraph with this sentence:

Always obey your parents, when they are present.

—MARK TWAIN, “Advice to Youth”