Identifying Toulmin’s elements of an argument

Page contents:

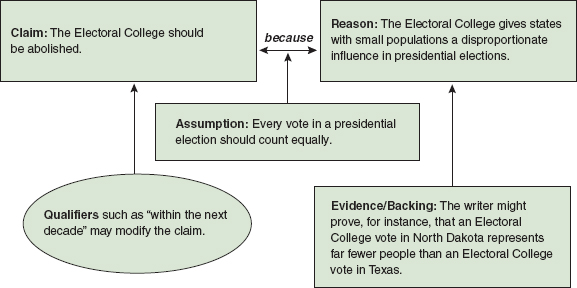

According to philosopher Stephen Toulmin’s framework for analyzing arguments, most arguments contain common features: a claim or claims; reasons for the claim; assumptions, whether stated or unstated, that underlie the argument (Toulmin calls these warrants); evidence or backing, such as facts, authoritative opinions, examples, and statistics; and qualifiers that limit the claim in some way.

Claims

Claims (also referred to as arguable statements) are statements that the writer wants to prove. In longer essays, you may detect a series of linked claims or even several separate claims that you need to analyze before you agree to accept them. Claims worthy of arguing are those that are debatable: to say “Ten degrees Fahrenheit is cold” is a claim, but it is probably not debatable—

Reasons

In fact, a claim is only as good as the reasons attached to it. If a student claims that course portfolios should be graded pass or fail because so many students in the class work full-

Assumptions

Putting a claim and reasons together often results in what Aristotle called an enthymeme, an argument that rests on an assumption the writer expects the audience to hold. These assumptions (which Toulmin calls warrants) that connect claim and reasons are often the hardest to detect in an argument, partly because they are often unstated, sometimes masking a weak link. As a result, it’s especially important to identify the assumptions in arguments you are analyzing. Once the assumption is identified, you can test it against evidence and your own experience before accepting it. If a writer argues that the Electoral College should be abolished because states with small populations have undue influence on the outcome of presidential elections, what is the assumption underlying this claim and reason? It is that presidential elections should give each voter the same amount of influence. As a critical reader, remember that such assumptions are deeply affected by culture and belief: ask yourself, then, what cultural differences may be at work in your response to any argument.

Evidence or backing

Evidence, which Toulmin calls backing, also calls for careful analysis in arguments. In an argument about abolishing the Electoral College, the writer may offer as evidence a statistical analysis of the number of voters represented by an Electoral College vote in the least populous states and in the most populous states; a historical discussion of why the Founding Fathers developed the Electoral College system; or psychological studies showing that voters in states where one political party dominates feel disengaged from presidential elections. As a critical reader, you must evaluate each piece of evidence the writer offers, asking specifically how it relates to the claim, whether it is appropriate and timely, and whether it comes from a credible source.

Qualifiers

Qualifiers offer a way of limiting or narrowing a claim so that it is as precise as possible. Words or phrases that signal a qualification include many, sometimes, in these circumstances, and so on. Claims having no qualifiers can sometimes lead to overgeneralizations. For example, the statement The Electoral College should be abolished is less precise than The Electoral College should be abolished by 2024. Look carefully for qualifiers in the arguments you analyze because they will affect the strength and reach of the claim.

Sample: Analysis of an advertisement

Look closely at the following advertisement. If you decide that this advertisement is claiming that people should adopt shelter pets, you might word a reason like this: Dogs and cats need people, not just shelter. You might note that the campaign assumes that people make pets happier (and that pets deserve happiness)—and that the image backs up the overall message that this inquisitive, well-