Identifying common fallacies

Page contents:

Fallacies have traditionally been viewed as serious flaws that damage the effectiveness of an argument. But arguments are ordinarily fairly complex in that they always occur in some specific rhetorical situation and in some particular place and time; thus, what looks like a fallacy in one situation may appear quite different in another. The best advice is to learn to identify fallacies but to be cautious in jumping to quick conclusions about them. Rather than thinking of them as errors you can root out and use to discredit an arguer, you might think of them as barriers to common ground and understanding because they so often shut off rather than engender debate. If a letter to the editor argues If this newspaper thinks additional tax cuts are going to help the middle-

Misleading images are also a form of fallacy. The sheer power of images can make them especially difficult to analyze—

Ad hominem

Ad hominem charges make a personal attack rather than focusing on the issue at hand.

Guilt by association

Guilt by association attacks someone’s credibility by linking that person with a person or activity that the audience will consider bad, suspicious, or untrustworthy.

False authority

False authority is often used by advertisers who show famous actors or athletes testifying to the greatness of a product about which they may know very little.

Bandwagon appeal

Bandwagon appeal suggests that a great movement is under way and the reader will be a fool or a traitor not to join it.

Flattery

Flattery tries to persuade readers by suggesting that they are thoughtful, intelligent, or perceptive enough to agree with the writer.

In-crowd appeal

In-

Veiled threat

Veiled threats try to frighten readers into agreement by hinting that they will suffer adverse consequences if they don’t agree.

False analogy

False analogies make comparisons between two situations that are not alike in important respects.

Begging the question

Begging the question is a kind of circular argument that treats a debatable statement as if it had been proved true.

Post hoc fallacy

The post hoc fallacy (from the Latin post hoc, ergo propter hoc, which means “after this, therefore caused by this”) assumes that just because B happened after A, it must have been caused by A.

Non sequitur

A non sequitur (Latin for “it does not follow”) attempts to tie together two or more logically unrelated ideas as if they were related.

Either-or fallacy

The either-

Hasty generalization

A hasty generalization bases a conclusion on too little evidence or on bad or misunderstood evidence.

Oversimplification

Oversimplification claims an overly direct relationship between a cause and an effect.

Straw man

A straw-

Misleading photographs

Faked or altered photos have existed since the invention of photography, and fakes continue to surface. Here, for example, are an original photograph of an Iranian missile launch and the doctored image, showing a fourth launching missile, that Iran released to demonstrate its military might.

Today’s technology makes such photo alterations easier than ever, if also easier to detect. But photographs need not be altered to try to fool viewers. Think of all the photos that make a politician look misleadingly bad or good. In these cases, you should closely examine the motives of those responsible for publishing the images.

Misleading charts and graphs

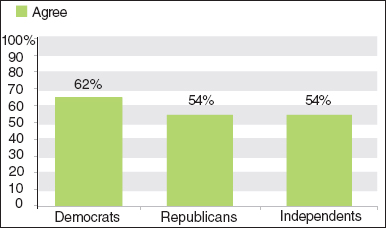

Facts and statistics can be presented in ways that mislead readers. For example, the following bar graph purports to deliver an argument about how differently Democrats, on the one hand, and Republicans and Independents, on the other, felt about an issue:

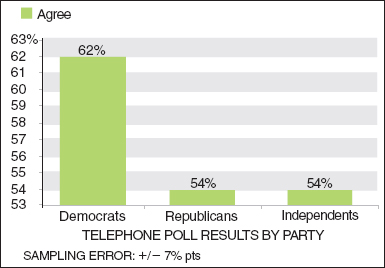

Look closely and you’ll see a visual fallacy at work: the vertical axis starts not at zero but at 53 percent, so the visually large difference between the groups is misleading. In fact, a majority of all respondents agree about the issue, and only 8 percentage points separate Democrats from Republicans and Independents (in a poll with a margin of error of ±7 percentage points). Here’s how the graph would look if the vertical axis began at zero: