Chapter 2. DIVERSITY IV—FUNGI

Learning Objectives

General Purpose

Conceptual

- Be able to compare and contrast the major groups within the kingdom Fungi.

- Be able to recognize and describe the structures important in fungi reproduction.

Background Information

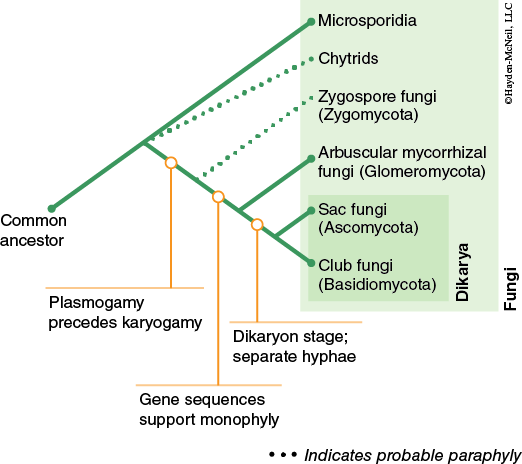

We will use the classification scheme that divides the fungal kingdom into six groups (see Figure 12-5).

Of the six groups we will consider four in lab: Chytridiomycota, the chytrids; Zygomycota, zygomycetes or zygote fungi; Ascomycota, ascomycetes or sac fungi; and Basidiomycota, basiodiomycetes or club fungi. Many of the characteristics that distinguish the groups are related to their reproduction.

Phylum Chytridiomycota

The chytrids are a predominantly aquatic group that can be found living in ditches, ponds, and streams. The chytrids are the only group of fungi with flagellated reproductive cells (zoospores and gametes). As noted in Figure 12-5 the chytrids may be a paraphyletic group and work is ongoing to ascertain the correct phylogenetic relationship of these organisms. Some species of chytrids are parasitic and others saprobic. Several species of the chytrids are plant pathogens. One remarkable species described in 1999 may be responsible for the deaths of frogs and amphibians in a number of ecosystems in North America and Australia. It is possible that this species may be a major contributor to the worldwide amphibian decline noted over the past two decades.

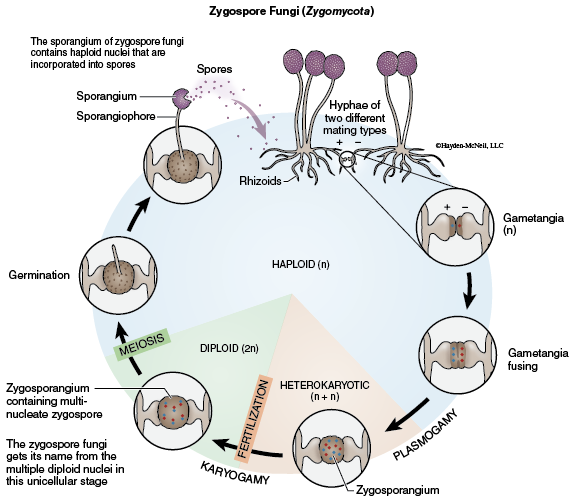

Phylum Zygomycota

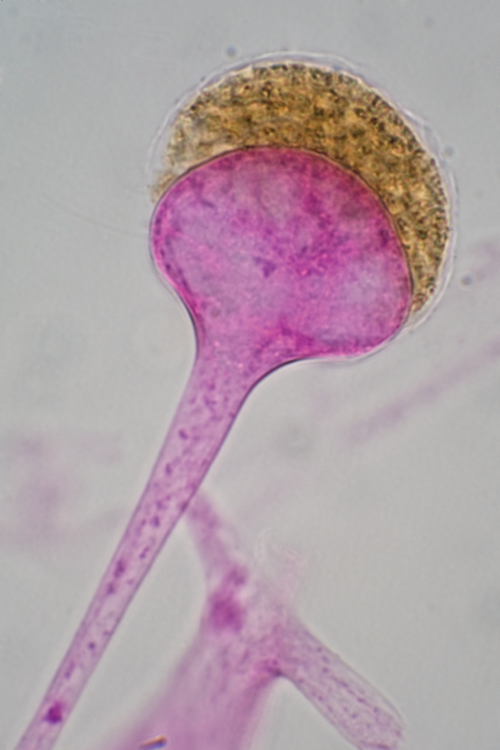

The name of this phylum comes from the sexually produced zygospores that develop within thick-walled structures called zygosporangia (see Figure 12-6).

The zygospores are resistant to many different environmental conditions and often persist for long periods of time. Zygomycete hyphae are coenocytic, although septa do appear during the formation of reproductive structures. These fungi are mostly terrestrial and live on decaying plant and animal matter or in the soil; others form mycorrhizae with some of our important crop plants. Like the chytrids the zygomycetes may likely be paraphyletic and the final phylogenetic tree is a work in progress. Several groups of zygomycetes are specialized associates of arthropods. In fact, one species is often found in the gut of crayfish; others kill flies. A familiar zygomycete is the black bread mold, Rhizopus stolonifer.

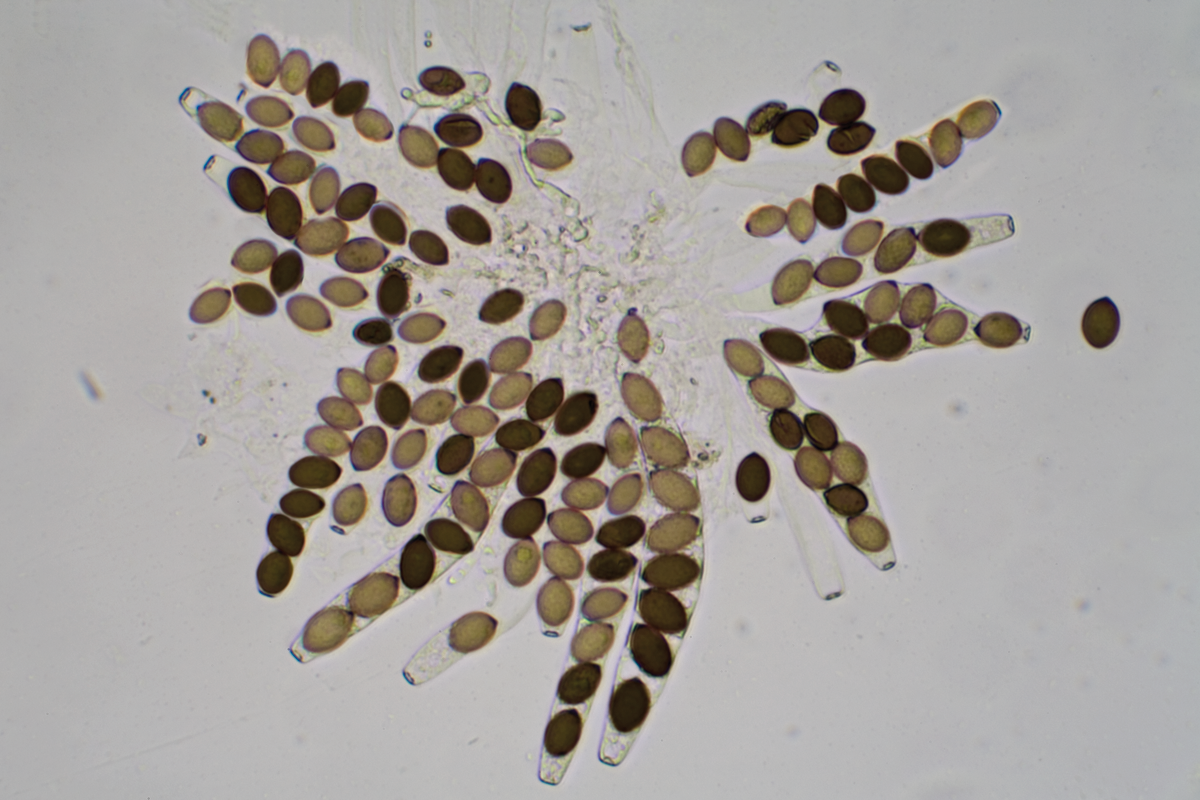

Phylum Ascomycota

The members of this group are unified by a common characteristic: they all possess a reproductive body called an ascus, a sac-like structure within which haploid ascospores (usually eight) are produced (see Figure 12-7).

The ascus develops as the result of sexual reproduction. Typically asexual reproduction is by formation of spores known as conidia. Ascomycetes, with the exception of the unicellular yeasts, have filamentous growth forms. A few ascomycetes, including some of the species that cause often-fatal human disease, are said to be dimorphic because they grow as filaments at ambient temperature and as unicellular yeasts in the human body at a higher temperature. The vegetative hyphae of ascomycetes have perforated septa that are best visualized with the electron microscope. This phylum includes diverse forms: unicellular yeasts, powdery mildews, molds such as the familiar blue-green mold that causes food spoilage, and complex cup fungi.

Phylum Basidiomycota

The distinguishing characteristic of this phylum is the production of basidiospores, sexual spores which are borne on the outside of a club-shaped spore-producing cell called the basidium (plural basidia). Basidia are formed at the ends of dikaryotic hyphae in large reproductive structures or fruiting bodies such as a mushroom. The two nuclei fuse and undergo meiosis within the basidium. Sexual reproduction is the principal means of reproduction in the Basidiomycota, although some produce conidia like those seen in the ascomycetes.

Many of the largest and most conspicuous fungi—the mushrooms, toadstools, puffballs, and bracket fungi (also known as shelf fungi)—are basidiomycetes (see Figure 12-8).

Also included in this phylum are the rusts and smuts, important plant pathogens that cause enormous losses in wheat, corn, and cereal crops. Although the aboveground portion of many of these fungi looks like a solid mass of tissue, they are still composed of hyphae. It should be emphasized that the prominent mushroom, toadstool, or shelf fungus is only a small part of the whole fungus; most of the fungus is beneath the ground or ramifying through the substrate it is using as a nutrition source. Members of the Basidiomycota play a major role in decomposition of organic matter in the soil and in wood. Although mushrooms are rather transient because they decay soon after the spores are formed and dispersed, the brackets (or shelves) are longer-lasting, and many examples can be found on living trees on or near the campus.

Fungal Forms with Unique Lifestyles

Certain modes of living that involve both morphological and ecological specialization have evolved independently among the Zygomycetes, the Ascomycetes, and the Basidiomycetes. These lifestyles allow the fungi to take advantage of unusual habitats.

Molds—Multiple Phyla

A mold is a rapidly growing, asexually reproducing fungus. The fungus may or may not reproduce sexually. The mycelia grow as saprobes or parasites on a variety of substrates. Some molds are important in the commercial production of antibiotics and some types of cheeses.

Yeasts

Yeasts are unicellular fungi that are adapted to living in liquid or moist habitats. They reproduce asexually by budding, where the parent cell produces a small outgrowth, the bud, which breaks off and then develops into another yeast cell. The yeasts are classified as yeasts based on lifestyle rather than a phylogenetic relationship. Most yeasts are classified in the Ascomycota phylum; however, others are classified as Zygomycota or Basidiomycota.

For centuries, humans have used the fermentation capacity of the genus Saccharomyces to make bread dough rise and produce a variety of beers and wines. Yeasts produce certain acids, alcohols, and gases as by-products of their metabolism of sugars. Other species of yeasts cause problems for humans, such as the unsightly pink growth on shower curtains and vaginal and oral yeast infections. A large number of yeast species are associated with insects, and many species of leafhoppers and beetles have yeast cultures in their gut. These yeasts may produce enzymes that help the insects digest their food.

Lichens

Lichens are mutualistic symbiotic partnerships between fungi, usually ascomycetes, and photosynthetic chlorophyta or cyanobacteria. In most cases, each partner provides things the other could not obtain. The photosynthetic organism provides a carbon source and organic nitrogen for itself and the fungus. The fungus, in return, provides absorption of water and minerals as well as a suitable environment (support and protection) for growth of the photosynthetic organism. Together, these symbionts form a unique structure capable of surviving in extremely harsh environments. The ability of lichens to survive under harsh environments is related to their ability to withstand desiccation and remain dormant when dry. Lichens characteristically occur in one of three basic forms: crustose (crust-like), foliose (leaf-like), and fruticose (shrub-like).

Mycorrhizae

Mycorrhizae (“fungus roots”) are mutualistic associations between fungi and the roots of most vascular plants. Some mycorrhizal fungi surround the plant cells while others actually invade the root cells. The hyphae of the mycorrhizal fungi greatly increase the plant’s ability to absorb water and essential elements. They also provide protection against attack by pathogenic fungi and nematodes (small roundworms). The plants provide the fungal partner with carbohydrates and vitamins essential for growth. The zygomycetes, ascomycetes, and basidiomycetes all have members that form mycorrhizae.

Parasitic Fungi

Although many fungi are beneficial, some are parasitic and attack organisms. This may result in the host being weakened to the point where they die. The Zygomycota, Ascomycota, and Basidiomycota all include parasitic species. Hosts represent a wide range of organisms including plants, animals, and even other fungi.