R1-d: Searching efficiently; mastering a few shortcuts to finding good sources

Most students use a combination of library databases and the Web in their research. You can save yourself a lot of time by becoming an efficient searcher.

Using the library

The Web site hosted by your college library is full of useful information. In addition to dozens of databases and links to other references, many libraries offer online subject guides as well as one-on-one help from reference librarians through e-mail or chat. You can save yourself time if you get advice from your instructor, a librarian, or your library’s Web site about the best place to start your search for sources.

Savvy searchers cut down on the clutter of a broad search by adding additional search terms, limiting a search to recent publications, or clicking on a database option to look at only one type of source, such as peer-reviewed articles. When looking for books, you can broaden a catalog search by asking yourself “What kind of book might contain the information I need?” After you’ve identified a promising book on the library shelves, looking through the books on nearby shelves can also be valuable.

Using the Web

When using a search engine, it’s a good idea to use terms that are as specific as possible and to enclose search phrases in quotation marks. You can refine your search by date or by domain; for example, autism site:. gov will search for information about autism on government (.gov) Web sites. Use clues in what you find (such as organizations or government agencies that seem particularly informative) to refine your search.

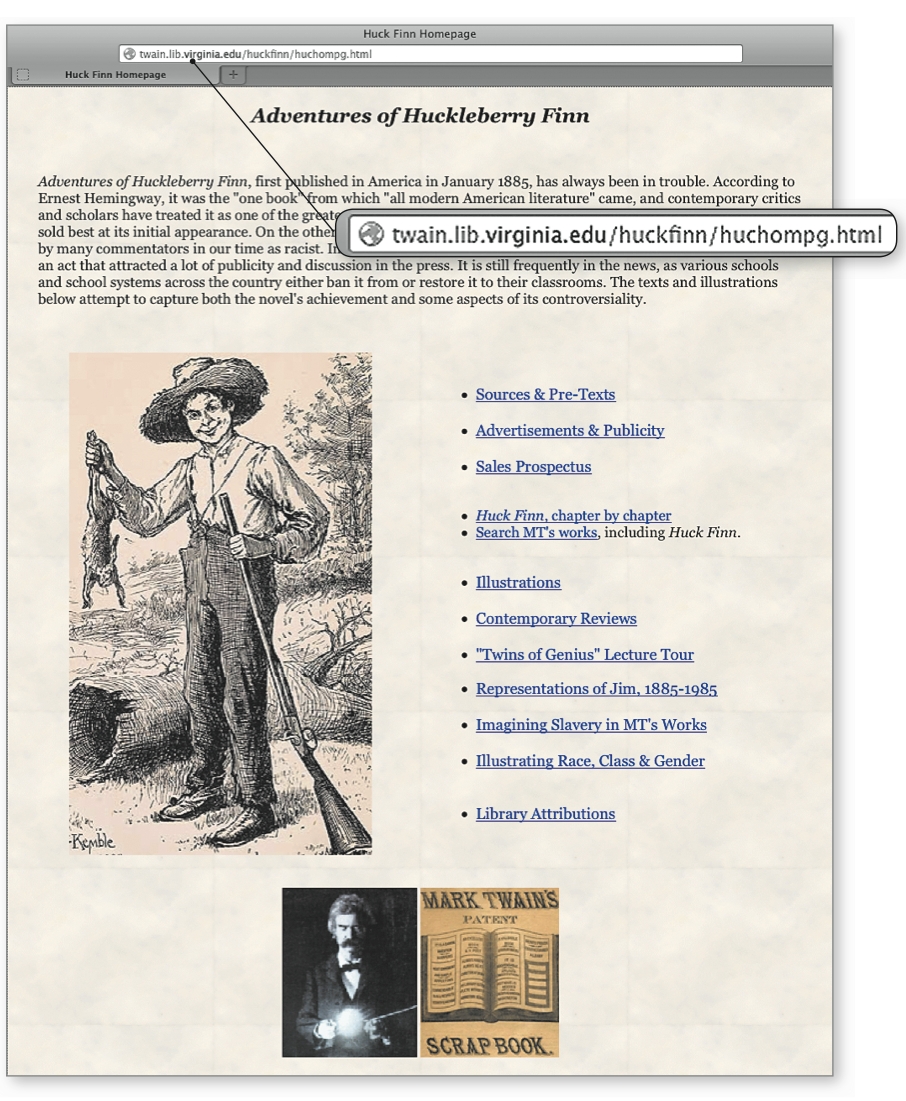

As you examine sites, look for “about” links to learn about the site’s author or sponsoring agency. Examine URLs for clues. Those that contain .k12 may be intended for young audiences; URLs ending in .gov lead to official information from US government entities. URLs may also offer clues about the country of origin: .au for Australia, .uk for United Kingdom, .in for India, and so on. If you aren’t sure where a page originated, erase everything in the URL after the first slash in your address bar; the result should be the root page of the site, which may offer useful information about the site’s purpose and audience. Avoid sites that provide information but no explanation of who the authors are or why the site was created. They may simply be advertising platforms attracting visitors with commonly sought information that is not original or substantial. For more on evaluating Web sites, see R3-c.

Using bibliographies and citations as shortcuts

MORE HELP IN YOUR HANDBOOK

Freewriting, listing, and clustering can help you come up with additional search terms.

Exploring your subject: C1-b

Scholarly books and articles list the works the author has cited, usually at the end. These lists are useful shortcuts to additional reliable sources on your topic. For example, most of the scholarly articles that student writer Luisa Mirano consulted contained citations to related research studies, selected by experts in the field. Through these citations, she quickly located other sources related to her topic, treatments for childhood obesity. Even popular sources such as news articles, videos, and interviews may refer to additional relevant sources that may be worth tracking down.

check urls for clues about sponsorship

Using a variety of online tools and databases

You will probably find that your instructor, your librarian, or your library’s Web site can be helpful in pointing you in the right direction once you have a topic and a research question. If you are still seeking some guidance about which Web sites, directories, databases, and other sources might yield useful searches, consult the chart Locating sources using online tools and databases, where you will find lists of sources that might provide just the jump start you are looking for.

Tips for smart searching

For currency

If you need current information, news outlets such as the New York Times and the BBC, think tanks, government agencies, and advocacy groups may provide appropriate sources for your research. When using Google, limit a search to the most recent year, month, week, or day.

For authority

As you search, keep an eye out for experts being cited in sources you examine. Following the citation trail may lead you to sources by those experts—or the organizations they represent—that may be even more helpful. You can limit a Google search by type of Web site and type of source. Add site:.gov to focus on government sources or filetype:pdf to zero in on reports and research papers as PDF files.

For scholarship

When you need scholarly or peer-reviewed articles, use a library database to look for reports of original research written by the people who conducted it. You’ll know you’re looking at a scholarly article if it provides information about where the authors work (universities, research centers), uses a formal writing style, and includes footnotes or a bibliography. Articles that are only one or two pages long are probably not scholarly. Don’t rule out an article just because it’s long. Read the abstract or the introductory paragraphs and the conclusion to see if the source is worth further investigation.

For context

Books are important sources in many fields such as history, philosophy, and sociology, and they often do a better job than scholarly articles of putting ideas in context. You may find a single chapter or even a few pages that are just what you need to gain a deeper perspective. Consider publication dates with your topic in mind.

For firsthand authenticity

In some fields, primary sources may be required. In historical research, for example, a primary source is one that originated in the historical period under discussion or is a firsthand account from a witness. In the sciences, a primary source (sometimes called a primary article) is a published report of research written by the scientist who conducted it. For more information, see R3-c.