1.1.6 At Work

At Work

35

In their daily lives at home and in church, Trackton adults and children have worked out ways of integrating features of both oral and written language in their language uses. But what of work settings and contacts with banks, credit offices, and the employment office—institutions typical of modernized, industrial societies?

36

Most of the adults in Trackton worked in the local textile mills. To obtain these jobs, they went directly to the employment office of the individual mills. There, an employment officer read to them from an application form and wrote down their answers. They were not asked if they wanted to complete their own form. They were given no written information at the time of their application, but the windows and walls of the room in which they waited for personal interviews were plastered with posters about the credit union policy of the plant and the required information for filling out an application (names of previous employers, Social Security number, etc.). But all of this information was known to Trackton residents before they went to apply for a job. Such information and news about jobs usually passed by word of mouth. Some of the smaller mills put advertisements in the local paper and indicated they would accept applications during certain hours on particular days. Interviewers either told individuals at the time of application they had obtained jobs, or the employment officer agreed to telephone in a few days. If applicants did not have telephones, they gave a neighbor’s number, or the mill sent a postcard.

37

Once accepted for the job, totally inexperienced workers would be put in the particular section of the mill in which they were to work, and were told to watch experienced workers. The foreman would occasionally check by to see if the observer had questions and understood what was going on. Usually before the end of the first few hours on the shift, the new worker was put under the guidance of certain other workers and told to share work on a particular machine. Thus, in an apprentice-like way new workers came on for new jobs, and they worked in this way for only several days, since all parties were anxious for this arrangement to end as soon as possible. Mills paid in part on a piece-work basis, and each machine operator was anxious to be freed to work at his or her own rapid pace as soon as possible. Similarly, the new worker was anxious to begin to be able to work rapidly enough to qualify for extra pay.

38

Within each section of the mill, little written material was in evidence. Safety records, warnings, and, occasionally, reports about new products, or clippings from local newspapers about individual workers or events at the mill’s recreational complex, would be put up on the bulletin board. Foremen and quality control personnel came through the mill on each shift, asking questions, noting output, checking machines, and recording this information. They often asked the workers questions, and the information would be recorded on a form carried by the foreman or quality control engineer. Paychecks were issued each Friday, and the stub carried information on Federal and state taxes withheld, as well as payments for health plans or automatic payments made for credit loans from the credit bureau. Mill workers generally kept these stubs in their wallets, or in a special box (often a shoe box, sometimes a small metal filebox) at home. They were rarely referred to at the time of issuance of the paycheck, unless a recent loan had been taken out or paid off at the credit bureau. Then workers would check the accuracy of the amounts withheld. In both the application stage and on the job, workers had to respond to a report or a form being filled out by someone else. This passive performance with respect to any actual reading or writing did not occur because the workers were unable to read and write. Instead, these procedures were the results of the mill’s efforts to standardize the recording and processing of information. When asked why they did not let applicants fill out their own employment form, employment officers responded:

It is easier if we do it. This way, we get to talk to the client, ask questions not on the form, clarify immediately any questions they have, and, for our purposes, the whole thing is just cleaner. When we used to have them fill out the forms, some did it in pencil, others had terrible handwriting, others gave us too much or too little information. This way, our records are neat, and we know what we’ve got when someone has finished an application form.

39

In the past, job training at some of the mills had not been done ‘on the floor,’ but through a short session with manuals, an instructor, and instruction ‘by the book.’ Executives of the mills found this process too costly and inefficient, and those who could do the best job of handling the written materials were not necessarily the best workers on the line.

40

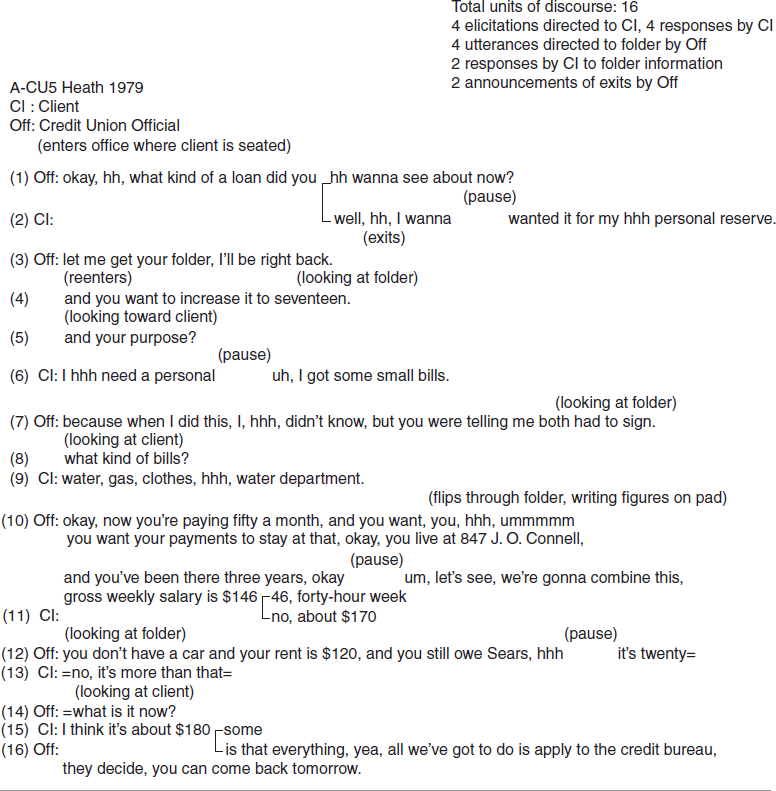

Beyond the mill, Trackton adults found in banks, credit union offices, and loan offices the same type of literacy events. The oral performance surrounding a written piece of material to which they had little or no access was what counted or made a difference in a transaction. When individuals applied for credit at the credit union, the interviewer held the folder, asked questions derived from information within the folder, and offered little or no explanation of the information from which he derived questions. At the end of interviews, workers did not know whether or not they would receive the loan or what would be done with the information given to the person who interviewed them. In the following interview (see Figure 1), the credit union official directs questions to the client primarily on the basis of what is in the written documents in the client’s folder.2 She attempts to reconcile the written information with the current oral request. However, the client is repeatedly asked to supply information as though she knows the contents of the written document. Referents for pronouns (it in 4, this in 7, this in 10, and they in 16) are not clearly identified, and the client must guess at their referents without any visual or verbal clues. Throughout this literacy event, only one person has access to the written information, but the entire oral exchange centers around that information. In (4) the credit union employee introduces new information; it refers to the amount of the current loan. The record now shows that the client has a loan which is being repaid by having a certain amount deducted from her weekly paycheck; for those in her salary range, there is an upper limit of $1700 for a loan.

41

But this information is not clear from the oral exchange, and it is known only to the credit union employee and indicated on documents in the client’s folder. The calculation of a payment of $50 per month (10) is based on this information, and the way in which this figure was derived is never explained to the client. In (10) the official continues to read from the folder, but she does not ask for either confirmation or denial of this information. Her ambiguous statement, ‘We’re gonna combine this’, can only be assumed to mean the current amount of the loan with the amount of the new loan, the two figures which will now equal the total of the new principal $1,700. The statement of gross weekly salary as $146.66 is corrected by the client (11), but the official does not verbally acknowledge the correction; she continues writing. Whether she records the new figure and takes it into account in her calculations is not clear. The official continues reading (12) and is once again corrected by the client. She notes the new information and shortly closes off the interview.

42

In this literacy event, written materials have determined the outcome of the request, yet the client has not been able to see those documents or frame questions which would clarify their contents. This pattern occurred frequently for Trackton residents, who argued that neighborhood center programs and other adult education programs should be aimed not at teaching higher level reading skills or other subjects, but at ways of getting through such interviews or other situations (such as visits to dentists and doctors), when someone else held the information which they needed to know in order to ask questions about the contents of that written material in ways which would be acceptable to institution officials.