10.1 Utility: Getting Satisfaction

When analyzing consumer behaviour, we’re talking about people trying to get satisfaction—

The utility of a consumer is a measure of the satisfaction the consumer derives from consumption of goods and services.

Luckily, we don’t need to make comparisons between your feelings and mine. All that is required to analyze consumer behaviour is to suppose that each individual is trying to maximize some personal measure of the satisfaction gained from consumption of goods and services. That measure is known as the consumer’s utility, a concept we use to understand behaviour but don’t expect to measure in practice. Nonetheless, we’ll see that the assumption that rational consumers maximize utility helps us think clearly about consumer choice.

Utility and Consumption

An individual’s consumption bundle is the collection of all the goods and services consumed by that individual.

An individual’s utility depends on everything that individual consumes, from apples to Ziploc bags. The set of all the goods and services an individual consumes is known as the individual’s consumption bundle. The relationship between an individual’s consumption bundle and the total amount of utility it generates for that individual is known as the utility function. The utility function is a personal matter; two people with different tastes will have different utility functions. Someone who actually likes to consume 40 chicken wings at a sitting must have a utility function that looks different from that of someone who would rather stop at 5 wings.

An individual’s utility function gives the total utility generated by his or her consumption bundle.

So we can think of consumers as using consumption to “produce” utility, much in the same way as in later chapters we will think of producers as using inputs to produce output. However, it’s obvious that people do not have a little computer in their heads that calculates the utility generated by their consumption choices. Nonetheless, people must make choices, and they usually base them on at least a rough attempt to decide which choice will give them greater satisfaction. I can have either soup or salad with my dinner. Which will I enjoy more? I can go on a big vacation this year or save the money toward buying a new car. Which will make me happier?

The concept of a utility function is just a way of representing the fact that when people consume, they take into account their preferences and tastes in a more or less rational way.

A util is a unit of utility.

How do we measure utility? For the sake of simplicity, it is useful to suppose that we can measure utility in hypothetical units called—

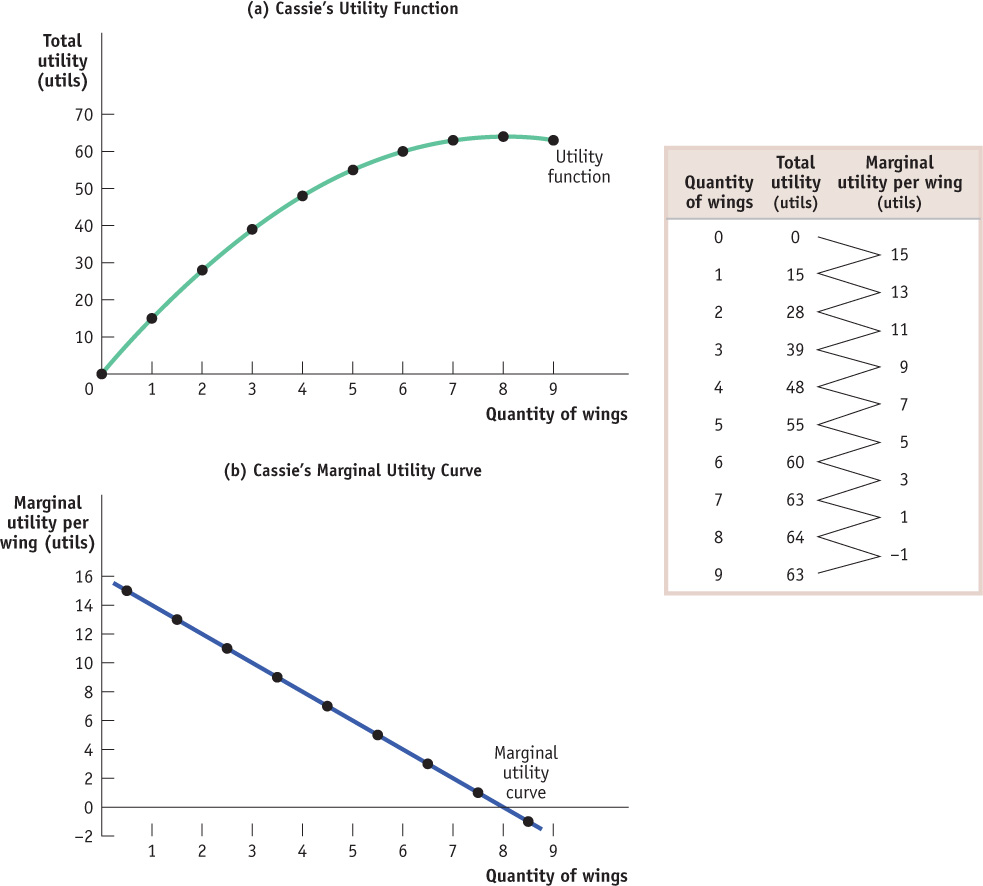

Figure 10-1 illustrates a utility function. It shows the total utility that Cassie, who likes chicken wings, gets from an all-

Cassie’s utility function slopes upward over most of the range shown, but it gets flatter as the number of wings consumed increases. And in this example it eventually turns downward. According to the information in the table in Figure 10-1, nine wings is a wing too far. Adding that additional wing actually makes Cassie worse off: it would lower her total utility. If she’s rational, of course, Cassie will realize that and not consume the ninth wing.

So when Cassie chooses how many wings to consume, she will make this decision by considering the change in her total utility from consuming one more wing. This illustrates the general point: to maximize total utility, consumers must focus on marginal utility.

The Principle of Diminishing Marginal Utility

In addition to showing how Cassie’s total utility depends on the number of wings she consumes, the table in Figure 10-1 also shows the marginal utility generated by consuming each additional wing—that is, the change in total utility from consuming one additional wing. Panel (b) shows the implied marginal utility curve. Following our practice in Chapter 9 with the marginal benefit curve, the marginal utility curve is constructed by plotting points at the midpoint of the unit intervals.1

The marginal utility of a good or service is the change in total utility generated by consuming one additional unit of that good or service.

The marginal utility curve shows how marginal utility depends on the quantity of a good or service consumed.

The marginal utility curve slopes downward: each successive wing adds less to total utility than the previous wing. This is reflected in the table: marginal utility falls from a high of 15 utils for the first wing consumed to –1 for the ninth wing consumed. The fact that the ninth wing has negative marginal utility means that consuming it actually reduces total utility. (Restaurants that offer all-you-can-eat meals depend on the proposition that you can have too much of a good thing.) Not all marginal utility curves eventually become negative. But it is generally accepted that marginal utility curves do slope downward—that consumption of most goods and services is subject to diminishing marginal utility.

IS MARGINAL UTILITY REALLY DIMINISHING?

Are all goods really subject to diminishing marginal utility? Of course not; there are a number of goods for which, at least over some range, marginal utility is surely increasing.

For example, there are goods that require some experience to enjoy. The first time one of the Canadian authors tried indoor rock climbing, the fear of falling kept her close to the ground. Once she overcame her fear, a few sessions later, climbing became very enjoyable. It only becomes a pleasurable activity if you do it enough to become reasonably competent. And even some less strenuous forms of consumption take practice; people who are not accustomed to drinking coffee say it has a bitter taste and can’t understand its appeal. (On the other hand, two of the authors regard coffee as one of the basic food groups.)

Another example would be goods that only deliver positive utility if you buy enough. The great Victorian economist Alfred Marshall, who more or less invented the supply and demand model, gave the example of wallpaper: buying only enough to do half a room is worse than useless. If you need two rolls of wallpaper to finish a room, the marginal utility of the second roll is larger than the marginal utility of the first roll.

So why does it make sense to assume diminishing marginal utility? For one thing, most goods don’t suffer from these qualifications: nobody needs to learn to like ice cream. Also, although most people don’t rock climb and some people don’t drink coffee, those who do rock climb or drink coffee do enough of it that the marginal utility of one more climbing session or one more cup is less than that of the last. So in the relevant range of consumption, marginal utility is still diminishing.

The basic idea behind the principle of diminishing marginal utility is that the additional satisfaction a consumer gets from one more unit of a good or service declines as the amount of that good or service consumed rises.2 Or, to put it slightly differently, the more of a good or service you consume, the closer you are to being satiated—reaching a point at which an additional unit of the good adds nothing to your satisfaction. For someone who almost never gets to eat a banana, the occasional banana is a marvellous treat. (This was the case in Eastern Europe before the fall of communism, when bananas were very hard to find.) For someone who eats them all the time, a banana is just, well, a banana.

According to the principle of diminishing marginal utility, each successive unit of a good or service consumed adds less to total utility than the previous unit.

The principle of diminishing marginal utility isn’t always true. But it is true in the great majority of cases, enough to serve as a foundation for our analysis of consumer behaviour.

OYSTERS VERSUS CHICKEN

Is a particular food a special treat, something you consume on special occasions? Or is it an ordinary, take-it-or-leave-it dish? The answer depends a lot on how much of that food people normally consume, which determines how much utility they get at the margin from having a bit more.

Consider chicken. Modern North Americans eat a lot of chicken, so much that they regard it as nothing special. Yet this was not always the case. Traditionally chicken was a luxury dish because chickens were expensive to raise. Restaurant menus from two centuries ago show chicken dishes as the most expensive items listed. In 1928, Herbert Hoover ran for president of the United States on the slogan “A chicken in every pot,” a promise to voters of great prosperity if he was elected.

What changed the status of chicken was the emergence of new, technologically advanced methods for raising and processing the birds. (You don’t want to know.) These methods made chicken abundant, cheap, and also—thanks to the principle of diminishing marginal utility—nothing to get excited about.

The reverse evolution took place for oysters. Not everyone likes oysters or, for that matter, has ever tried them—they are definitely not ordinary food. But they are regarded as a delicacy by some; at restaurants that serve them, an oyster appetizer often costs more than the main course.

Yet oysters were once very cheap and abundant—and were regarded as poverty food. In The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens, published in the 1830s, the author remarks that “poverty and oysters always seem to go together.”

What changed? Pollution, which destroyed many oyster beds, greatly reduced the supply, while human population growth greatly increased the demand. As a result, thanks to the principle of diminishing marginal utility, oysters went from being a common food, regarded as nothing special, to being a highly prized luxury good.

Quick Review

Utility is a measure of a consumer’s satisfaction from consumption, expressed in units of utils. Consumers try to maximize their utility. A consumer’s utility function shows the relationship between the consumption bundle and the total utility it generates.

To maximize utility, a consumer considers the marginal utility from consuming one more unit of a good or service, illustrated by the marginal utility curve.

In the consumption of most goods and services, and for most people, the principle of diminishing marginal utility holds: each successive unit consumed adds less to total utility than the previous unit.

Check Your Understanding 10-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 10-1

Question 10.1

Explain why a rational consumer who has diminishing marginal utility for a good would not consume an additional unit when it generates negative marginal utility, even when that unit is free.

Consuming a unit that generates negative marginal utility leaves the consumer with lower total utility than not consuming that unit at all. A rational consumer, a consumer who maximizes utility, would not do that. For example, from Figure 10-1 you can see that Cassie receives 64 utils if she consumes 8 wings; but if she consumes the 9th wing, she loses a util, netting her a total utility of only 63 utils. So whenever consuming a unit generates negative marginal utility, the consumer is made better off by not consuming that unit, even when that unit is free.

Question 10.2

Marta drinks three cups of coffee a day, for which she has diminishing marginal utility. Which of her three cups generates the greatest increase in total utility? Which generates the least?

Since Marta has diminishing marginal utility of coffee, her first cup of coffee of the day generates the greatest increase in total utility. Her third and last cup of the day generates the least.

Question 10.3

In each of the following cases, does the consumer have diminishing, constant, or increasing marginal utility? Explain your answers.

The more Mabel exercises, the more she enjoys each additional visit to the gym.

Although Mei’s classical CD collection is huge, her enjoyment from buying another CD has not changed as her collection has grown.

When Dexter was a struggling student, his enjoyment from a good restaurant meal was greater than now, when he has them more frequently.

Mabel has increasing marginal utility of exercising since each additional unit consumed brings more additional enjoyment than the previous unit.

Mei has constant marginal utility of CDs because each additional unit generates the same additional enjoyment as the previous unit.

Dexter has diminishing marginal utility of restaurant meals since the additional utility generated by a good restaurant meal is less when he consumes lots of them than when he consumed few of them.