13.4 Monopoly and Public Policy

It’s good to be a monopolist, but it’s not so good to be a monopolist’s customer. A monopolist, by reducing output and raising prices, benefits at the expense of consumers. But buyers and sellers always have conflicting interests. Is the conflict of interest under monopoly any different than it is under perfect competition?

The answer is yes, because monopoly is a source of inefficiency: the losses to consumers from monopoly behaviour are larger than the gains to the monopolist. Because monopoly leads to net losses for the economy, governments often try either to prevent the emergence of monopolies or to limit their effects. In this section, we will see why monopoly leads to inefficiency and examine the policies governments adopt in an attempt to prevent this inefficiency.

Welfare Effects of Monopoly

By restricting output below the level at which marginal cost is equal to the market price, a monopolist increases its profit but hurts consumers. To assess whether this is a net benefit or loss to society, we must compare the monopolist’s gain in profit to the loss in consumer surplus. And what we learn is that the loss in consumer surplus is larger than the monopolist’s gain. Monopoly causes a net loss for society.

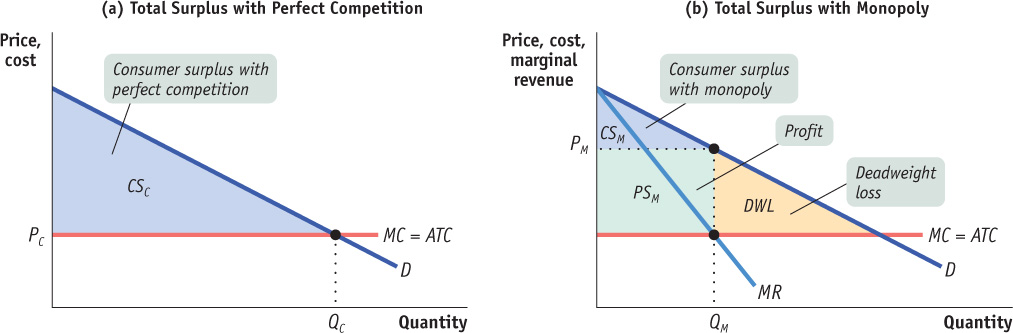

To see why, let’s return to the case where the marginal cost curve is horizontal, as shown in the two panels of Figure 13-8. Here the marginal cost curve is MC, the demand curve is D, and, in panel (b), the marginal revenue curve is MR.

Panel (b) depicts the industry under monopoly: the monopolist decreases output to QM and charges PM. Consumer surplus (blue area) has shrunk: a portion of it has been captured as profit (green area), and a portion of it has been lost to deadweight loss (orange area), the value of mutually beneficial transactions that do not occur because of monopoly behaviour. As a result, total surplus falls.

Panel (a) shows what happens if this industry is perfectly competitive. Equilibrium output is QC; the price of the good, PC, is equal to marginal cost, and marginal cost is also equal to average total cost because there is no fixed cost and marginal cost is constant. Each firm is earning exactly its average total cost per unit of output, so there is no profit and no producer surplus in this equilibrium. The consumer surplus generated by the market is equal to the area of the blue-

Panel (b) shows the results for the same market, but this time assuming that the industry is a monopoly. The monopolist produces the level of output QM, at which marginal cost is equal to marginal revenue, and it charges the price PM. The industry now earns profit—

By comparing panels (a) and (b), we see that in addition to the redistribution of surplus from consumers to the monopolist, another important change has occurred: the sum of profit and consumer surplus—

This net loss arises because some mutually beneficial transactions do not occur. There are people for whom an additional unit of the good is worth more than the marginal cost of producing it but who don’t consume it because they are not willing to pay PM.

If you recall our discussion of the deadweight loss from taxes in Chapter 7 you will notice that the deadweight loss from monopoly looks quite similar. Indeed, by driving a wedge between price and marginal cost, monopoly acts much like a tax on consumers and produces the same kind of inefficiency.

So monopoly hurts the welfare of society as a whole and is a source of market failure. Is there anything government policy can do about it?

Preventing Monopoly

Policy toward monopoly depends crucially on whether or not the industry in question is a natural monopoly, one in which increasing returns to scale ensure that a bigger producer has lower average total cost. If the industry is not a natural monopoly, the best policy is to prevent monopoly from arising or break it up if it already exists. Let’s focus on that case first, then turn to the more difficult problem of dealing with natural monopoly.

The De Beers monopoly on diamonds didn’t have to happen. Diamond production is not a natural monopoly: the industry’s costs would be no higher if it consisted of a number of independent, competing producers (as is the case, for example, in gold production).

So if the South African government had been worried about how a monopoly would have affected consumers, it could have blocked Cecil Rhodes in his drive to dominate the industry or broken up his monopoly after the fact. Today, governments often try to prevent monopolies from forming and break up existing ones.

De Beers is a rather unique case: for complicated historical reasons, it was allowed to remain a monopoly. But over the last century, most similar monopolies have been broken up. A noted example of breaking up a monopoly in Canada is Bell Canada. Bell Canada used to be the monopoly provider of certain telephone services in most of Canada east of Manitoba and in the territories. Starting in the 1980s, the federal government began to deregulate the country’s telecommunications industry; as new firms were allowed to enter the market Bell Canada gradually lost its monopoly status. The most celebrated example in the United States is Standard Oil, founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1870. By 1878 Standard Oil controlled almost all U.S. oil refining; but in 1911 a court order broke the company into a number of smaller units, including the companies that later became Exxon and Mobil (and more recently merged to become ExxonMobil).

The government policies used to prevent or eliminate monopolies are known as competition or antitrust policy, which we will discuss in the next chapter.

Dealing with Natural Monopoly

Breaking up a monopoly that isn’t natural is clearly a good idea: the gains to consumers outweigh the loss to the producer. But it’s not so clear whether a natural monopoly, one in which a large producer has lower average total costs than small producers, should be broken up, because this would raise average total cost. For example, a municipal government that tried to prevent a single company from dominating local gas supply—which, as we’ve discussed, is almost surely a natural monopoly—would raise the cost of providing gas to its residents.

Yet even in the case of a natural monopoly, a profit-maximizing monopolist acts in a way that causes inefficiency—it charges consumers a price that is higher than marginal cost and, by doing so, prevents some potentially beneficial transactions. Also, it can seem unfair that a firm that has managed to establish a monopoly position earns a large profit at the expense of consumers.

What can public policy do about this? There are two common answers.

Public Ownership In many countries, the preferred answer to the problem of natural monopoly has been public ownership. Instead of allowing a private monopolist to control an industry, the government establishes a public agency to provide the good and protect consumers’ interests. In Britain, for example, telephone service was provided by the state-owned British Telecom before 1984, and airline travel was provided by the state-owned British Airways before 1987. (These companies still exist, but they have been privatized, competing with other firms in their respective industries.)

In public ownership of a monopoly, the good is supplied by the government or by a firm owned by the government.

In Canada, the government has often assumed control of a monopoly industry by nationalizing it. Publicly owned companies in Canada are called Crown corporations. They may be owned by any level of government—federal, provincial, territorial, or municipal government. Federally owned Crown corporations include Canada Post, Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, Via Rail Canada, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, and the Bank of Canada. Most electric utilities are Crown corporations at either the provincial level (BC Hydro, Ontario Power Generation, Hydro One, Hydro-Québec, and NB Hydro), territorial level (Northwest Territories Power), or municipal level (Toronto Hydro, EPCOR, ENMAX, London Hydro). In past decades, some governments have privatized some of their Crown corporations, such as Air Canada, Petro Canada, the Canadian National Railway, Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc., and Nova Scotia Power, as discussed in the previous Economics in Action.

The advantage of public ownership, in principle, is that a publicly owned natural monopoly can set prices based on the criterion of efficiency rather than profit maximization as we saw with the Nova Scotia Power Corporation. In a perfectly competitive industry, profit-maximizing behaviour is efficient, because producers produce the quantity at which price is equal to marginal cost; that is why there is no economic argument for public ownership of, say, wheat farms.

Experience suggests, however, that public ownership as a solution to the problem of natural monopoly often works badly in practice. One reason is that publicly owned firms are often less eager than private companies to keep costs down or offer high-quality products. Another is that publicly owned companies all too often end up serving political interests—providing contracts or jobs to people with the right connections. For example, the public U.S. company Amtrak has notoriously provided train service at a loss to destinations that attract few passengers—but that are located in the districts of influential politicians.

Regulation An alternative to operating a natural monopoly as a Crown corporation is to leave the industry in private hands but subject it to regulation. In particular, most local utilities like electricity, land line telephone service, natural gas, and so on are covered by price regulation that limits the prices they can charge.

Price regulation limits the price that a monopolist is allowed to charge.

We saw in Chapter 5 that imposing a price ceiling on a competitive industry is a recipe for shortages, black markets, and other nasty side effects. Doesn’t imposing a limit on the price that, say, a local gas company can charge have the same effects?

Not necessarily: a price ceiling on a monopolist need not create a shortage—in the absence of a price ceiling, a monopolist would charge a price that is higher than its marginal cost of production. So even if forced to charge a lower price—as long as that price is above MC and the monopolist at least breaks even on total output—the monopolist still has an incentive to produce the quantity demanded at that price.

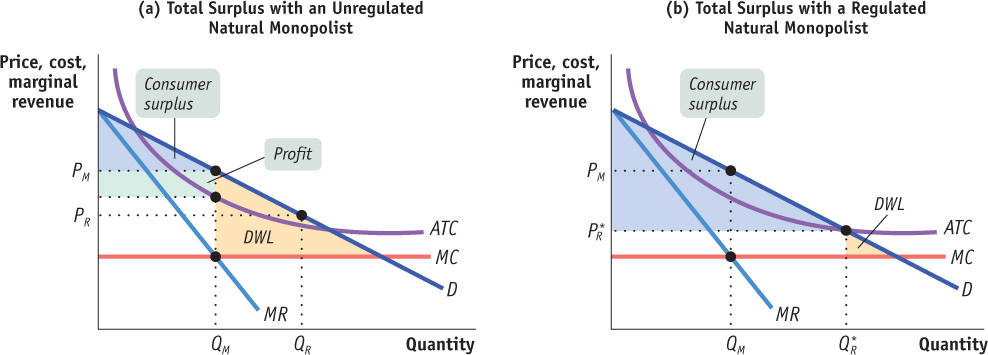

Figure 13-9 shows an example of price regulation of a natural monopoly—a highly simplified version of a local gas company. The company faces a demand curve D, with an associated marginal revenue curve MR. For simplicity, we assume that the firm’s total costs consist of two parts: a fixed cost and variable costs that are incurred at a constant proportion to output. So marginal cost is constant in this case, and the marginal cost curve (which here is also the average variable cost curve) is the horizontal line MC. The average total cost curve is the downward-sloping curve ATC; it slopes downward because the higher the output, the lower the average fixed cost (the fixed cost per unit of output). Because average total cost slopes downward over the range of output relevant for market demand, this is a natural monopoly.

Panel (b) shows what happens when the monopolist must charge a price equal to average total cost, the price

. Output expands to Q*R, and consumer surplus is now the entire blue area. The monopolist makes zero profit. This is the greatest total surplus possible when the monopolist is allowed to at least break even, making

. Output expands to Q*R, and consumer surplus is now the entire blue area. The monopolist makes zero profit. This is the greatest total surplus possible when the monopolist is allowed to at least break even, making  the best regulated price.

the best regulated price.Panel (a) illustrates a case of natural monopoly without regulation. The unregulated natural monopolist chooses the monopoly output QM and charges the price PM. Since the monopolist receives a price greater than its average total cost, it earns a profit. This profit is exactly equal to the producer surplus in this market, represented by the green-shaded rectangle. Consumer surplus is given by the blue-shaded triangle. Deadweight loss is given by the orange-shaded triangle.

Now suppose that regulators impose a price ceiling on local gas deliveries—one that falls below the monopoly price PM but above ATC, say, at PR in panel (a). At that price the quantity demanded is QR.

Does the company have an incentive to produce that quantity? Yes. If the price at which the monopolist can sell its product is fixed by regulators, the firm’s output no longer affects the market price—so it ignores the MR curve and is willing to expand output to meet the quantity demanded as long as the price it receives for the next unit is greater than marginal cost and the monopolist at least breaks even on total output. So with price regulation, the monopolist produces more, at a lower price.

Of course, the monopolist will not be willing to produce at all if the imposed price means producing at a loss. That is, the price ceiling has to be set high enough to allow the firm to cover its average total cost. Panel (b) shows a situation in which regulators have pushed the price down as far as possible, at the level where the average total cost curve crosses the demand curve. The practice of regulating the monopoly to set a price equal to its average total cost is called average cost pricing. At any lower price the firm loses money. The price here, P*R, is the best regulated price: the monopolist is just willing to operate and produces Q*R, the quantity demanded at that price. Consumers and society gain as a result.

Average cost pricing is a form of price regulation that forces a monopoly to set its price equal to its average total cost.

The welfare effects of this regulation can be seen by comparing the shaded areas in the two panels of Figure 13-9. Consumer surplus is increased by the regulation, with the gains coming from two sources. First, profits are eliminated and added instead to consumer surplus. Second, the larger output and lower price lead to an overall welfare gain—an increase in total surplus. In fact, panel (b) illustrates the largest total surplus possible. An alternative way to look at the welfare effect of this regulation is to look at the change in the deadweight loss. By adopting average cost pricing, the size of deadweight loss falls.

Looking at Figure 13-9, it may seem like the best solution is to force the monopolist to charge a price equal to their marginal cost—another type of price regulation is marginal cost pricing. However, when a natural monopolist faces a fixed cost, its average cost will usually be higher than its marginal cost, so marginal cost pricing implies the monopoly will always operate at a loss and it will choose to shut down. In order for marginal cost pricing to work, the government would need to provide a subsidy to the monopolist so that the firm can cover its fixed cost. So even though marginal cost pricing is most efficient for the market, it is seldom used in practice.

Marginal cost pricing is a form of price regulation that forces a monopoly to set its price equal to its marginal cost.

Regulating natural monopolies looks terrific: consumers are better off, profits are eliminated, and overall welfare increases. Unfortunately, things are rarely that easy in practice. The main problem is that regulators don’t have the information required to set the price exactly at the level at which the demand curve crosses the average total cost curve. Sometimes they set it too low, creating shortages; at other times they set it too high. Also, regulated monopolies, like publicly owned firms, tend to exaggerate their costs to regulators and to provide inferior quality to consumers.

Must Monopoly Be Controlled? Sometimes the cure is worse than the disease. Some economists have argued that the best solution, even in the case of natural monopoly, may be to live with it. The case for doing nothing is that attempts to control monopoly will, one way or another, do more harm than good—for example, by the politicization of pricing, which leads to shortages, or by the creation of opportunities for political corruption.

The following Economics in Action describes the case of wheat, a natural monopoly that has been regulated and deregulated as politicians change their minds about the appropriate policy.

CHANGE WAS BREWING

The Canadian Wheat Board (CWB), one of Canada’s biggest exporters and one of the world’s largest grain marketing organizations, was once a monopoly for the sale of western wheat and barley destined for export from Canada. The CWB also controlled the domestic sale of wheat and barley. Established by the Canadian Wheat Board Act of 1935, the CWB was an attempt to stabilize income for the wheat farmers in the Prairies. The CWB sells wheat and barley on behalf of its members, which aims at avoiding competition among members so that CWB can command higher return for everyone.

The farmers under the CWB’s jurisdiction were required to deliver their crops to the CWB and any selling of their crops via other channels was illegal; for them, the CWB was a monopsony (a single buyer). However, it was also a monopoly for anyone buying Canadian wheat and barley. The federal government ended the mandatory use of the CWB in 2012, removing its monopoly power. Now, Canada’s western wheat farmers have the option to sell their crops directly in the market or to continue to work with the CWB. By the same token, buyers of Canadian wheat can purchase this grain directly from the producers or through the CWB.

The ending of the monopoly of the Canadian Wheat Board was controversial. Many farmers believe that by handling the delivery of their crops themselves, they can obtain better prices, and have the freedom to deliver their crops to whomever they want and whenever they want. However, supporters of the CWB argue that when the CWB has market power, it is more efficient at marketing Canadian wheat and can negotiate higher prices for its members, freeing farmers to focus on growing crops rather than finding buyers and making their farms more productive. It will still be a few years before we can properly evaluate the effects of the ending of the CWB’s monopoly on the market and the general well-being of western wheat farmers.

Quick Review

By reducing output and raising price above marginal cost, a monopolist captures some of the consumer surplus as profit and causes deadweight loss. To avoid deadweight loss, government policy attempts to curtail monopoly behaviour.

When monopolies are “created” rather than natural, governments should act to prevent them from forming and break up existing ones.

Natural monopoly poses a harder policy problem. One answer is public ownership, but publicly owned companies are often poorly run.

Another alternative is price regulation. A price ceiling imposed on a monopolist does not create shortages as long as it is not set too low.

Ways to regulate monopolies include requiring them to set the price charged equal to either their average total cost (average cost pricing) or their marginal cost (marginal cost pricing).

There always remains the option of doing nothing; monopoly is a bad thing, but the cure may be worse than the disease.

Check Your Understanding 13-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 13-3

Question 13.6

What policy should the government adopt in the following cases? Explain.

Internet service in Anytown, Prince Edward Island, is provided by cable. Customers feel they are being overcharged, but the cable company claims it must charge prices that let it recover the costs of laying cable.

The only two airlines that currently fly to Yukon need government approval to merge. Other airlines wish to fly to Yukon but need government-allocated landing slots to do so.

Cable Internet service is a natural monopoly. So the government should intervene only if it believes that price exceeds average total cost, where average total cost is based on the cost of laying the cable. In this case it should impose a price ceiling equal to average total cost. Otherwise, it should do nothing.

The government should approve the merger only if it fosters competition by transferring some of the company’s landing slots to another, competing airline.

Question 13.7

True or false? Explain your answer.

Society’s welfare is lower under monopoly because some consumer surplus is transformed into profit for the monopolist.

A monopolist causes inefficiency because there are consumers who are willing to pay a price greater than or equal to marginal cost but less than the monopoly price.

False. As can be seen from Figure 13-8, panel (b), the inefficiency arises from the fact that some of the consumer surplus is transformed into deadweight loss (the yellow area), not that it is transformed into profit (the green area).

True. If a monopolist sold to all customers who have a valuation greater than or equal to marginal cost, all mutually beneficial transactions would occur and there would be no deadweight loss.

Question 13.8

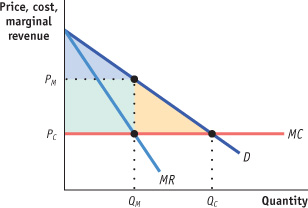

Suppose a monopolist mistakenly believes that its marginal revenue is always equal to the market price. Assuming constant marginal cost and no fixed cost, draw a diagram comparing the level of profit, consumer surplus, total surplus, and deadweight loss for this misguided monopolist compared to a smart monopolist.

As shown in the accompanying diagram, a profit–maximizing monopolist produces QM, the output level at which MR = MC. A monopolist who mistakenly believes that P = MR produces the output level at which P = MC (when, in fact, P > MR, and at the true profit-maximizing level of output, P > MR = MC). This misguided monopolist will produce the output level QC, where the demand curve crosses the marginal cost curve—the same output level produced if the industry were perfectly competitive. It will charge the price PC, which is equal to marginal cost, and make zero profit. The entire shaded area is equal to the consumer surplus, which is also equal to total surplus in this case (since the monopolist receives zero producer surplus). There is no deadweight loss since every consumer who is willing to pay as much as or more than marginal cost gets the good. A smart monopolist, however, will produce the output level QM and charge the price PM. Profit equals the green area, consumer surplus corresponds to the blue area, and total surplus is equal to the sum of the green and blue areas. The yellow area is the deadweight loss generated by the monopolist.