14.2 Understanding Oligopoly

How much will a firm produce? Up to this point, we have always answered: the quantity that maximizes its profit. Together with its cost curves, the assumption that a firm maximizes profit is enough to determine its output when it is a perfect competitor or a monopolist.

When it comes to oligopoly, however, we run into some difficulties. Indeed, economists often describe the behaviour of oligopolistic firms as a “puzzle.”

A Duopoly Example

An oligopoly consisting of only two firms is a duopoly. Each firm is known as a duopolist.

Let’s begin looking at the puzzle of oligopoly with the simplest version, an industry in which there are only two producing firms—

Going back to our opening story, imagine that Nestlé and Mars are the only two producers of chocolate. To make things even simpler, suppose that once a company has incurred the fixed cost needed to produce chocolate, the marginal cost of producing another kilogram is zero. So the companies are concerned only with the revenue they receive from sales because maximizing revenue results in maximum profit.

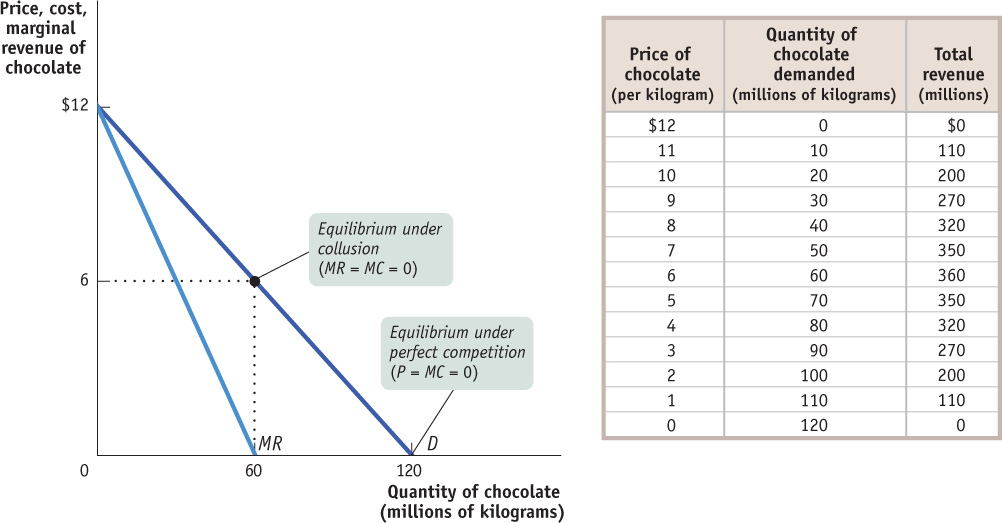

Figure 14-1 shows a hypothetical demand schedule for chocolate and the total revenue of the industry at each price–

If this were a perfectly competitive industry, each firm would have an incentive to produce more as long as the market price was above marginal cost. Since the marginal cost is assumed to be zero, this would mean that at equilibrium chocolate would be provided free. Firms would produce until price equals zero (the marginal cost), yielding a total output of 120 million kilograms and zero revenue for both firms.

However, surely the firms would not be that stupid. With only two firms in the industry, each would realize that by producing more, it drives down the market price. So each firm would, like a monopolist, realize that profits would be higher if it and its rival limited their production.

So how much will the two firms produce?

Sellers engage in collusion when they cooperate to raise their joint profits. A cartel is an agreement among several producers to obey output restrictions in order to increase their joint profits.

One possibility is that the two companies will engage in collusion—they will cooperate to raise their joint profits. The strongest form of collusion is a cartel, an arrangement between producers that determines how much each is allowed to produce. The world’s most famous cartel is the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, described in Economics in Action later in the chapter. As its name indicates, it’s actually an agreement among governments rather than firms. There’s a reason this most famous of cartels is an agreement among governments: cartels among firms are illegal in Canada and many other jurisdictions. But let’s ignore the law for a moment (which is, of course, what Nestlé and Mars did in real life—

So suppose that Nestlé and Mars were to form a cartel and that this cartel decided to act as if it were a monopolist, maximizing total industry profits. It’s obvious from Figure 14-1 that in order to maximize the combined profits of the firms, this cartel should set total industry output at 60 million kilograms of chocolate, which would sell at a price of $6 per kilogram, leading to revenue of $360 million, the maximum possible. (Recall that when marginal cost is zero, maximizing revenue results in maximizing profit.) Then the only question would be how much of that 60 million kilograms each firm gets to produce. A “fair” solution might be for each firm to produce 30 million kilograms with revenues for each firm of $180 million.

But even if the two firms agreed on such a deal, they might have a problem: each of the firms would have an incentive to break its word and produce more than the agreed-

Collusion and Competition

Suppose that the presidents of Nestlé and Mars were to agree that each would produce 30 million kilograms of chocolate over the next year. Both would understand that this plan maximizes their combined profits. And both would have an incentive to cheat.

To see why, consider what would happen if Mars honoured its agreement, producing only 30 million kilograms, but Nestlé ignored its promise and produced 40 million kilograms. This increase in total output would drive the price down from $6 to $5 per kilogram, the price at which 70 million kilograms are demanded. The industry’s total revenue would fall from $360 million ($6 × 60 million kilograms) to $350 million ($5 × 70 million kilograms). However, Nestlé’s revenue would rise, from $180 million to $200 million. Since we are assuming a marginal cost of zero, this would mean a $20 million increase in Nestlé’s profits.

But Mars’s president might make exactly the same calculation. And if both firms were to produce 40 million kilograms of chocolate, the price would drop to $4 per kilogram. So each firm’s profits would fall, from $180 million to $160 million.

Why do individual firms have an incentive to produce more than the quantity that maximizes their joint profits? Because neither firm has as strong an incentive to limit its output as a true monopolist would.

Let’s go back for a minute to the theory of monopoly. We know that a profit-maximizing monopolist sets marginal cost (which in this case is zero) equal to marginal revenue. But what is marginal revenue? Recall that producing an additional unit of a good has two effects:

A positive quantity effect: an additional unit is sold, increasing total revenue by the price at which that unit is sold.

A negative price effect: in order to sell an additional unit, the monopolist must cut the market price on all units sold.

The negative price effect is the reason marginal revenue for a monopolist is less than the market price. In the case of oligopoly, when considering the effect of increasing production, a firm is concerned only with the price effect on its own units of output, not those of its fellow oligopolists. Both Nestlé and Mars suffer a negative price effect if Nestlé decides to produce extra chocolate and so drives down the price. But Nestlé cares only about the negative price effect on the units it produces, not about the loss to Mars.

This tells us that an individual firm in an oligopolistic industry faces a smaller price effect from an additional unit of output than does a monopolist; therefore, the marginal revenue that such a firm calculates is higher. So it will seem to be profitable for any one company in an oligopoly to increase production, even if that increase reduces the profits of the industry as a whole. But if everyone thinks that way, the result is that everyone earns a lower profit!

Until now, we have been able to analyze producer behaviour by asking what a producer should do to maximize profits. But even if Nestlé and Mars are both trying to maximize profits, what does this predict about their behaviour? Will they engage in collusion, reaching and holding to an agreement that maximizes their combined profits? Or will they engage in noncooperative behaviour, with each firm acting in its own self-interest, even though this has the effect of driving down everyone’s profits? Both strategies sound like profit maximization. Which will actually describe their behaviour?

When firms ignore the effects of their actions on each others’ profits, they engage in noncooperative behaviour.

Now you see why oligopoly presents a puzzle: there are only a small number of players, making collusion a real possibility. If there were dozens or hundreds of firms, it would be safe to assume they would behave noncooperatively. Yet when there are only a handful of firms in an industry, it’s hard to determine whether collusion will actually materialize.

Since collusion is ultimately more profitable than noncooperative behaviour, firms have an incentive to collude if they can. One way to do so is to formalize it—sign an agreement (maybe even make a legal contract) or establish some financial incentives for the companies to set their prices high. But in Canada and many other nations, you can’t do that—at least not legally. Companies cannot make a legal contract to keep prices high: not only is the contract unenforceable, but writing it is a one-way ticket to jail. Neither can they sign an informal “gentlemen’s agreement,” which lacks the force of law but perhaps rests on threats of retaliation—that’s illegal, too.

In fact, executives from rival companies rarely meet without lawyers present, who make sure that the conversation does not stray into inappropriate territory. Even hinting at how nice it would be if prices were higher can bring you an unwelcome interview with the Competition Bureau. For example, in 2013 the Competition Bureau announced that Yazaki Corporation, a Japanese supplier of automobile parts, was fined a record $30 million, for participating in a bid-rigging cartel involving vehicle parts. Bid-rigging occurs when two or more firms work together to fix their bids for contracts so as to set prices and allocate the market amongst the group. Yazaki pleaded guilty to the charge that they had coordinated bids with competing suppliers for the Canadian operations of Honda and Toyota. Suppliers Furukawa and JTEKT each received $5 million fines. In the United States, Yazaki agreed to pay a US$470 million fine for price-fixing and bid-rigging, the second largest criminal fine to that time. Four U.S.-based Yazaki executives were given prison sentences of 15 months to two years for their roles in this criminal conspiracy.

Sometimes, as we’ve seen, oligopolistic firms just ignore the rules. But more often they find ways to achieve collusion without a formal agreement, as we’ll discuss later in the chapter.

PRICE FIXER TO THE WORLD

The world’s largest agricultural products company, Archer Daniels Midland (also known as ADM), has often described itself as “supermarket to the world.” Its name is familiar to many North Americans not only because of its important role in the economy but also because of its advertising and sponsorship of U.S. public television programs. But on October 25, 1993, ADM itself was on camera.

On that day executives from ADM and its Japanese competitor Ajinomoto met at the Marriott Hotel in Irvine, California, to discuss the market for lysine, an additive used in animal feed. (How is lysine produced? It’s excreted by genetically engineered bacteria.) In this and subsequent meetings, the two companies joined with several other competitors to set targets for the world market price of lysine, the illegal behaviour of price-fixing. Each company agreed to limit its production in order to achieve those targets. Agreeing on specific limits would be their biggest challenge—or so they thought.

Within the first year, the cartel was able to raise lysine prices by 70%. But what the participants in the meeting didn’t know was that they had a bigger problem: the FBI had bugged the room and was filming them with a camera hidden in a lamp. As dramatized in the 2009 movie The Informant, the FBI had been made aware of this criminal behaviour by Mark Whitacre (portrayed by Matt Damon in the movie), an ADM executive turned whistleblower. Thanks to all the evidence collected, ADM, Japanese firms Ajinomoto and Kyowa Hakko Kogyo, and Korean firms Sewon America Inc. and Cheil Jedang Ltd. all ended up pleading guilty to criminal charges related to this international cartel illegally fixing lysine prices from 1992 to 1996. Fines in the United States were US$105 million (US$70 million from ADM alone). Three former ADM executives were arrested for their role in this criminal conspiracy. In Canada, three of the firms were fined about $20 million ($16 million of that from ADM). North American buyers of lysine launched civil lawsuits to recover damages from the five cartel members. The civil suits were successful, and, when added to the criminal fines, doubled the settlement costs of the firms.

As a result of this sad adventure and other similar accusations, some took to calling ADM the “price fixer to the world.”

Quick Review

Some of the key issues in oligopoly can be understood by looking at the simplest case, a duopoly—an industry containing only two firms, called duopolists.

By acting as if they were a single monopolist, oligopolists can maximize their combined profits. So there is an incentive to form a cartel.

However, each firm has an incentive to cheat—to produce more than it is supposed to under the cartel agreement. So there are two principal outcomes: successful collusion or noncooperative behaviour by cheating.

Check Your Understanding 14-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 14-2

Question 14.3

Which of the following factors increase the likelihood that an oligopolist will collude with other firms in the industry? The likelihood that an oligopolist will act noncooperatively and raise output? Explain your answers.

The firm’s initial market share is small. (Hint: Think about the price effect.)

The firm has a cost advantage over its rivals.

The firm’s customers face additional costs when they switch from the use of one firm’s product to another firm’s product.

The oligopolist has a lot of unused production capacity but knows that its rivals are operating at their maximum production capacity and cannot increase the amount they produce.

The firm is likely to act noncooperatively and raise output, which will generate a negative price effect. But because the firm’s current market share is small, the negative price effect will fall much more heavily on its rivals’ revenues than on its own. At the same time, the firm will benefit from a positive quantity effect.

The firm is likely to act noncooperatively and raise output, which will generate a fall in price. Because its rivals have higher costs, they will lose money at the lower price while the firm continues to make profits. So the firm may be able to drive its rivals out of business by increasing its output.

The firm is likely to collude. Because it is costly for consumers to switch products, the firm would have to lower its price quite substantially (by increasing quantity a lot) to induce consumers to switch to its product. So increasing output is likely to be unprofitable given the large negative price effect.

The firm is likely to act uncooperatively because it knows its rivals cannot increase their output in retaliation.