16.3 Positive Externalities

Stretching from Niagara Falls through Hamilton and the Greater Toronto Area, the Golden Horseshoe region is probably the most densely populated region in the country, containing a large portion of Canada’s industry and about 9 million residents. Yet a drive through this region reveals a surprising feature: farm after farm, growing everything from corn to peaches to the famous Niagara grapes for ice wine. This situation is not an accident: the federal and provincial governments have passed laws that give tax subsidies to farmers who permanently preserve their farmland rather than sell it to developers. These subsidies have helped preserve thousands of hectares of open space.

Why have Canadian citizens raised their own tax burden to subsidize the preservation of farmland? Because they believe that preserved farmland in an already heavily developed area provides external benefits, such as natural beauty, access to fresh food, and the conservation of wild bird populations. In addition, preservation alleviates the external costs that come with more development, such as pressure on roads, water supplies, and municipal services—

In this section we’ll explore the topics of external benefits and positive externalities. They are, in many ways, the mirror images of external costs and negative externalities. Left to its own, the market will produce too little of a good (in this case, preserved Ontario farmland) that confers external benefits on others. But society as a whole is better off when policies are adopted that increase the supply of such a good.

Preserved Farmland: An External Benefit

Preserved farmland yields both benefits and costs to society. In the absence of government intervention, the farmer who wants to sell his or her land incurs all the costs of preservation—

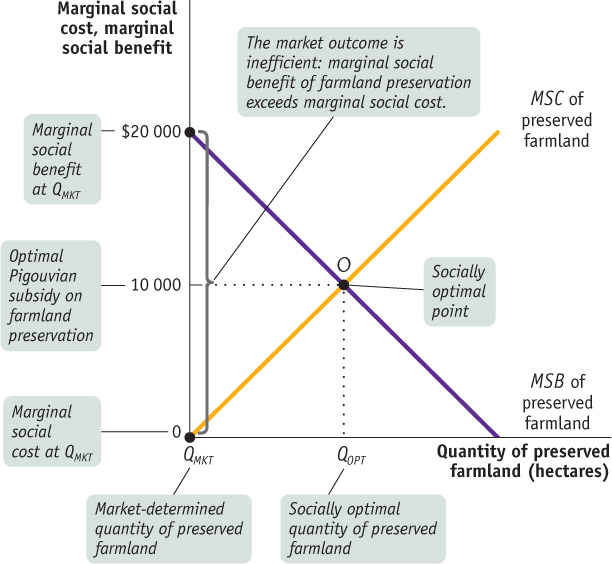

Figure 16-7 illustrates society’s problem. The marginal social cost of preserved farmland, shown by MSC, is the additional cost imposed on society by an additional hectare of such farmland. This represents the forgone profits that would have accrued to farmers if they had sold their land to developers. The line is upward-

The MSB curve represents the marginal social benefit of preserved farmland. It is the additional benefit that accrues to society—

The market alone will not provide QOPT hectares of preserved farmland. Instead, in the market outcome no hectares will be preserved; the level of preserved farmland, QMKT, is equal to zero. That’s because farmers will set the marginal social cost of preservation—

A Pigouvian subsidy is a payment designed to encourage activities that yield external benefits.

This is clearly inefficient because at zero hectares preserved, the marginal social benefit of preserving a hectare of farmland is $20 000. So how can the economy be induced to produce QOPT hectares of preserved farmland, the socially optimal level? The answer is a Pigouvian subsidy: a payment designed to encourage activities that yield external benefits. The optimal Pigouvian subsidy, as shown in Figure 16-7, is equal to the marginal social benefit of preserved farmland at the socially optimal level, QOPT—that is, $10 000 per hectare.

So Canadians are indeed implementing the right policy to raise their social welfare—

Positive Externalities in the Modern Economy

In the overall Canadian economy, the most important single source of external benefits is the creation of knowledge. In high-tech industries such as semiconductors, software design, green technology, and bioengineering, innovations by one firm are quickly emulated and improved upon by rival firms. Such spreading of knowledge across individuals and firms is known as a technology spillover. In the modern economy, the greatest sources of technology spillovers are major universities and research institutes.

A technology spillover is an external benefit that results when knowledge spreads among individuals and firms.

In technologically advanced countries such as Canada, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Israel, there is an ongoing exchange of people and ideas among private industries, major universities, and research institutes located in close proximity. The dynamic interplay that occurs in these research clusters spurs innovation and competition, theoretical advances, and practical applications. (See the Business Case at the end of the chapter for more on research clusters.)

One of Canada’s best known and most successful research clusters is located in the so-called Technology Triangle of Kitchener, Waterloo, and Cambridge, anchored by several universities and colleges, the Perimeter Institute, the Institute for Quantum Computing, a number of other research parks and incubators, plus companies such as BlackBerry, OpenText, and Google. Ultimately, these areas of technology spillover increase the economy’s productivity and raise living standards.

But research clusters don’t appear out of thin air. Except in a few instances in which firms have funded basic research on a long-term basis, research clusters have grown up around major universities. And like farmland preservation, major universities and their research activities are subsidized by government. In fact, government policy-makers in technologically advanced countries have long understood that the external benefits generated by knowledge, stemming from basic education to high-tech research, are key to the economy’s growth over time.

THE IMPECCABLE ECONOMIC LOGIC OF EARLY-CHILDHOOD INTERVENTION PROGRAMS

One of the most vexing problems facing any society is how to break what researchers call the “cycle of poverty”: children who grow up in disadvantaged socioeconomic circumstances are far more likely to remain trapped in poverty as adults, even after we account for differences in ability. They are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed, to engage in crime, and to suffer chronic health problems.

Early-childhood intervention has offered some hope of breaking the cycle. A 2006 study by the RAND Corporation found that high-quality early-childhood programs that focus on education and health care lead to significant social, intellectual, and financial advantages for kids who would otherwise be at risk of dropping out of high school and of engaging in criminal behaviour. Children in these programs were less likely to engage in such destructive behaviours and more likely to end up with a job and to earn a high salary later in life.

Another study by researchers at the University of Toronto in 2003 looked at early-childhood intervention programs from a dollars-and-cents perspective, estimating that a national child-care program launched in Canada could provide annual benefits worth $10.2 billion at a cost of $7.9 billion; a 29% return on investment. A similar U.S. study puts the rate of return in that country as high as $17 per $1 spent!

Quick Review

When there are positive externalities, or external benefits, a market economy, left to itself, will typically produce too little of the good or activity. The socially optimal quantity of the good or activity can be achieved by an optimal Pigouvian subsidy.

The most important example of external benefits in the economy is the creation of knowledge through technology spillover.

Check Your Understanding 16-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 16-3

Question 16.5

In 2010-2011, government grants to Canadian universities and colleges totalled almost $20 billion. The federal government channelled another $3 billion in grants and loans to students. Provincial and territorial governments also provided grants and loans to post-secondary students. Explain why this can be an optimal policy to encourage the creation of knowledge.

Post secondary education provides external benefits through the creation of knowledge. And government grants and student aid acts like a Pigouvian subsidy on higher education. If the marginal social benefit of higher education is $30 billion, then to obtain an optimal policy provincial and territorial governments need to provide $7 billion in student aid.

Question 16.6

In each of the following cases, determine whether an external cost or an external benefit is imposed and what an appropriate policy response would be.

Trees planted in urban areas improve air quality and lower summer temperatures.

Water-saving toilets reduce the need to pump water from rivers and aquifers. The cost of a litre of water to homeowners is virtually zero.

Old computer monitors contain toxic materials that pollute the environment when improperly disposed of.

Planting trees imposes an external benefit: the marginal social benefit of planting trees is higher than the marginal benefit to individual tree planters, since many people (not just those who plant the trees) can benefit from the increased air quality and lower summer temperatures. The difference between the marginal social benefit and the marginal benefit to individual tree planters is the marginal external benefit. A Pigouvian subsidy could be placed on each tree planted in urban areas in order to increase the marginal benefit to individual tree planters to the same level as the marginal social benefit.

Water-saving toilets impose an external benefit: the marginal benefit to individual homeowners from replacing a traditional toilet with a water-saving toilet is zero, since water is virtually costless. But the marginal social benefit is large, since fewer rivers and aquifers need to be pumped. The difference between the marginal social benefit and the marginal benefit to individual home-owners is the marginal external benefit. A Pigouvian subsidy on installing water-saving toilets could bring the marginal benefit to individual homeowners in line with the marginal social benefit.

Disposing of old computer monitors imposes an external cost: the marginal cost to those disposing of old computer monitors is lower than the marginal social cost, since environmental pollution is borne by people other than the person disposing of the monitor. The difference between the marginal social cost and the marginal cost to those disposing of old computer monitors is the marginal external cost. A Pigouvian tax on disposing of computer monitors, or a system of tradable permits for their disposal, could raise the marginal cost to those disposing of old computer monitors sufficiently to make it equal to the marginal social cost.