17.4 Artificially Scarce Goods

An artificially scarce good is a good that is excludable but nonrival in consumption. As we’ve already seen, on-demand movies are a familiar example. The marginal cost to society of allowing an individual to watch the movie is zero, because one person’s viewing doesn’t interfere with other people’s viewing. Yet CinemaNow and companies like it prevent an individual from seeing a movie if he or she hasn’t paid. Goods like computer software or audio files, which are valued for the information they embody (and are sometimes called “information goods”), are also artificially scarce.

An artificially scarce good is excludable but nonrival in consumption.

As we’ve already seen, markets will supply artificially scarce goods: because they are excludable, the producers can charge people for consuming them.

But artificially scarce goods are nonrival in consumption, which means that the marginal cost of an individual’s consumption is zero. So the price that the supplier of an artificially scarce good charges exceeds marginal cost. Because the efficient price is equal to the marginal cost of zero, the good is “artificially scarce,” and consumption of the good is inefficiently low. However, unless the producer can somehow earn revenue for producing and selling the good, he or she will be unwilling to produce at all—an outcome that leaves society even worse off than it would otherwise be with positive but inefficiently low consumption.

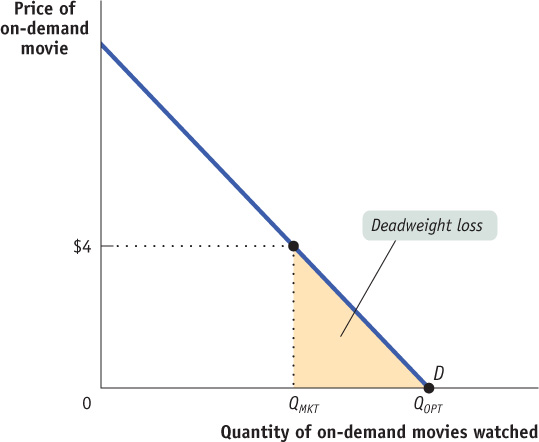

Figure 17-4 illustrates the loss in total surplus caused by artificial scarcity. The demand curve shows the quantity of on-demand movies watched at any given price. The marginal cost of allowing an additional person to watch the movie is zero, so the efficient quantity of movies viewed is QOPT. CinemaNow charges a positive price, in this case $4, to unscramble the signal, and as a result only QMKT on-demand movies will be watched. This leads to a deadweight loss equal to the area of the shaded triangle.

Does this look familiar? Like the problems that arise with public goods and common resources, the problem created by artificially scarce goods is similar to something we have already seen: in this case, it is the problem of natural monopoly. A natural monopoly, you will recall, is an industry in which average total cost is above marginal cost for the relevant output range. In order to be willing to produce output, the producer must charge a price at least as high as average total cost—that is, a price above marginal cost. But a price above marginal cost leads to inefficiently low consumption.

BLACKED-OUT GAMES

It’s the night of the big game for your local team—a game that is being nationally televised by one of the major networks. So you flip to the local channel that is an affiliate of that network—but the game isn’t on. Instead, you get some other show with a message scrolling across the bottom of the screen that this game has been blacked out in your area. What the message probably doesn’t say, though you understand quite well, is that this blackout is at the insistence of the team’s owners, who don’t want people who might have paid for tickets staying home and watching the game on TV instead. It used to be very common for games that failed to sell out their stadium tickets to be blacked out in local broadcast markets.

So the good in question—watching the game on TV—has been made artificially scarce. Because the game is being broadcast anyway, no scarce resources would be used to make it available in its immediate locality as well. But it isn’t available—which means a loss in welfare to those who would have watched the game on TV but are not willing to pay the price, in time and money, to go to the stadium.

Although CFL games on TSN may not air locally, the use of blackouts has become rare in Canada. Owners of NHL teams, for example, no longer feel they need to create artificial scarcity with local TV blackouts—the hockey arenas fill up easily as Canadians love the experience of watching hockey live.

Quick Review

An artificially scarce good is excludable but nonrival in consumption.

Because the good is nonrival in consumption, the efficient price to consumers is zero. However, because it is excludable, sellers charge a positive price, which leads to inefficiently low consumption.

The problems of artificially scarce goods are similar to those posed by a natural monopoly.

Check Your Understanding 17-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 17-4

Question 17.6

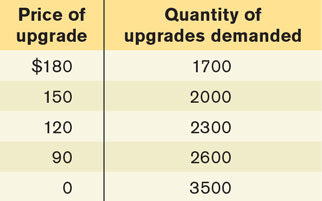

Xena is a software program produced by Xenoid. Each year Xenoid produces an upgrade that costs $300 000 to produce. It costs nothing to allow customers to download it from the company’s website. The demand schedule for the upgrade is shown in the accompanying table.

What is the efficient price to a consumer of this upgrade? Explain your answer.

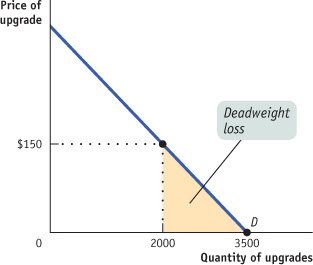

What is the lowest price at which Xenoid is willing to produce and sell the upgrade? Draw the demand curve and show the loss of total surplus that occurs when Xenoid charges this price compared to the efficient price.

The efficient price to a consumer is $0, since the marginal cost of allowing a consumer to download it is $0.

Xenoid will not produce the software unless it can charge a price that allows it at least to make back the $300 000 cost of producing it. So the lowest price at which Xenoid is willing to produce it is $150. At this price, it makes a total revenue of $150 × 2000 = $300 000; at any lower price, Xenoid will not cover its cost. The shaded area in the accompanying diagram shows the deadweight loss when Xenoid charges a price of $150.

Mauricedale Game Ranch and Hunting Endangered Animals to Save Them

John Hume’s Mauricedale ranch occupies 65 square kilometres in the hot, scrubby grasslands of northeastern South Africa. There he raises endangered species, such as black and white rhinos, and nonendangered species, such as Cape buffalo, antelopes, hippos, giraffes, zebras, and ostriches. From revenues of around $2.5 million per year, the ranch earns a small profit, with about 20% of the revenues coming from trophy hunting and 80% from selling live animals to farmers.

Although he entered this business to earn a profit, Hume sees himself as a conservator of these animals and this land. And he is convinced that in order to protect the black and white rhinos, some amount of legalized hunting of them is necessary. According to Hume, “rhinos are the most incredible animals on earth. I’m desperately sorry for them because they need our help.”

The story of one of Hume’s male rhinos, named “65,” illustrates his point. Hume and his staff knew that 65 was a problem: although too old to breed, he was belligerent enough to kill younger male rhinos. He was part of what wildlife conservationists call the “surplus male problem,” a male whose presence inhibits the growth of the herd.

Eventually, Hume obtained permission for the hunting of 65 from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), the international body that regulates the trade and legalized hunting of endangered species. A wealthy hunter paid Hume about $180 000, and the troublesome 65 was quickly dispatched.

Conservationist ranchers like Hume, who advocate regulated hunting of wildlife, point to the experience of Kenya to buttress their case. In 1977, Kenya banned the trophy hunting or ranching of wildlife. Since then, Kenya has lost 60% to 70% of its large wildlife through poaching or conversion of habitat to agriculture. Its herd of black rhinos, once numbered at 20 000, now stands at 600, surviving only in protected areas. In contrast, since regulated hunting of the less endangered white buffalo began in South Africa in 1968, its numbers have risen from 1800 to 19 400.

Many conservationists now agree that the key to recovery for a number of endangered species is legalized hunting on well-regulated game ranches—ranches that are actively engaged in breeding and maintaining the animals.

However, legalized hunting is currently a very controversial policy, strongly opposed by some wildlife advocates. Because establishing a ranch like Mauricedale requires a huge capital investment, many are concerned that smaller, fly-by-night ranches will engage in “canned hunts” with animals—often drugged or sick—obtained from elsewhere. And there is a fear that the high prices paid for trophy hunts will make ranchers too eager to cull animals from their herds. As of the time of writing, those advocating legalized hunting appear to be gaining ground.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 17.7

Using the concepts you learned in this chapter, explain the economic incentives behind the huge losses in Kenyan wildlife.

Question 17.8

Compare the economic incentives facing John Hume with those facing a Kenyan rancher.

Question 17.9

What regulations should be imposed on a rancher who sells opportunities to trophy hunt? Relate these to the concepts in the chapter.