19.3 Is the Marginal Productivity Theory of Income Distribution Really True?

Although the marginal productivity theory of income distribution is a well-

First, in the real world we see large disparities in income between factors of production that, in the eyes of some observers, should receive the same payment. Perhaps the most conspicuous examples in Canada are the large differences in the average wages between women and men and among various racial and ethnic groups. Do these wage differences really reflect differences in marginal productivity, or is something else going on?

Second, many people wrongly believe that the marginal productivity theory of income distribution gives a moral justification for the distribution of income,implying that the existing distribution is fair and appropriate. This misconception sometimes leads other people, who believe that the current distribution of income is unfair, to reject marginal productivity theory.

To address these controversies, we’ll start by looking at income disparities across gender and ethnic groups. Then we’ll ask what factors might account for these disparities and whether these explanations are consistent with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution.

Wage Disparities in Practice

Wage rates in Canada cover a very wide range. In 2014, hundreds of thousands of workers received the legal minimum wage, a rate that varies from $11 per hour in Nunavut and Ontario to $9.95 per hour in Alberta. The average minimum wage worker earns less than $22 000 per year if they are able to get 40 hours of work per week. At the other extreme, the chief executives of two dozen companies were paid more than $10 million, which works out to more than $27 000 per day even if they worked all 365 days of the year. Even leaving out these extremes, there is a huge range of wage rates. Are people really that different in their marginal productivities?

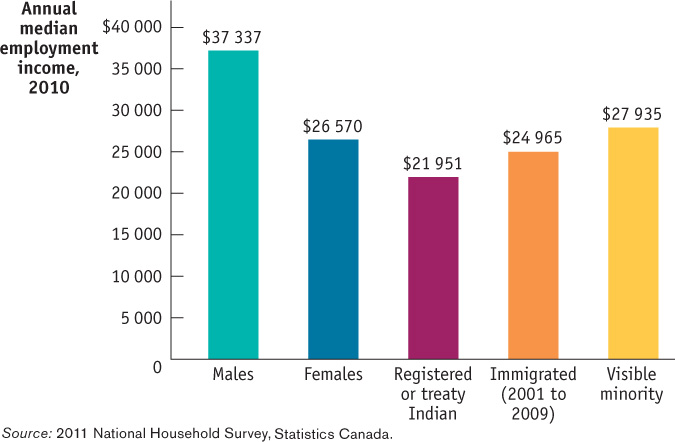

A particular source of concern is the existence of systematic wage differences across gender, ethnicity, and immigration status. Figure 19-8 compares annual median earnings in 2010 of workers age 15 or older classified by gender and ethnicity. As a group, males (averaging across all ethnicities and places of birth) had the highest earnings. Other data show that women (averaging across all ethnicities and places of birth) earned only about 71% as much; treaty Indian workers (male and female combined), only 59% as much; workers who immigrated between 2001 and 2009 (again, male and female combined), only 67% as much; visible minority workers (averaging across places of birth and gender) earned only about 75% as much.

We are a nation founded on the belief that every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination. So why do workers receive such unequal pay? Let’s start with the marginal productivity explanations, and then look at other influences.

Marginal Productivity and Wage Inequality

A large part of the observed inequality in wages can be explained by considerations that are consistent with the marginal productivity theory of income distribution. In particular, there are three well-

Compensating differentials are wage differences across jobs that reflect the fact that some jobs are less pleasant than others.

First is the existence of compensating differentials: across different types of jobs, wages are often higher or lower depending on how attractive or unattrac-

A second reason for wage inequality that is clearly consistent with marginal productivity theory is differences in talent. People differ in their abilities: a higher-

A third and very important reason for wage differences is differences in the quantity of human capital. Recall that human capital—

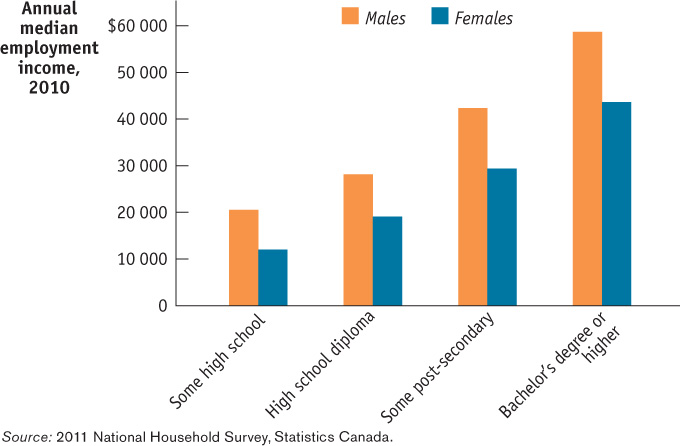

The most direct way to see the effect of human capital on wages is to look at the relationship between educational levels and earnings. Figure 19-9 shows earnings differentials by gender and four educational levels for people aged 15 or older in 2010. As you can see, regardless of gender, higher education is associated with higher median earnings. For example, in 2010 females without a high school diploma had median earnings 37% less than those with a high school diploma and 59% less than those with a post-

Because men typically have had more years of education than women, differences in levels of education are part of the explanation for the earnings differences shown in Figure 19-8.

It’s also important to realize that formal education is not the only source of human capital; on-

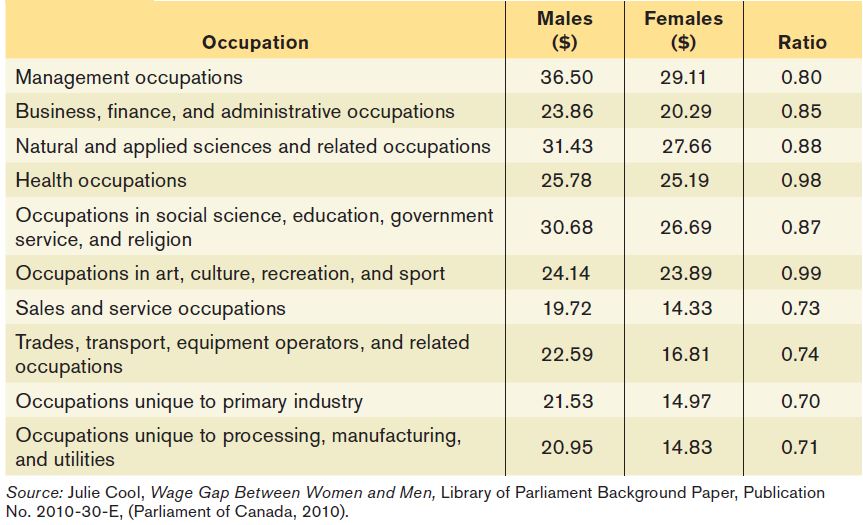

Table 19-3 shows the average hourly wage and the female-

But it’s also important to emphasize that earnings differences arising from differences in human capital are not necessarily “fair.” A society in which Aboriginal and immigrant children often receive a poor education because they live in underfunded school districts, then go on to earn low wages because they are poorly educated, may have labour markets that are well described by marginal productivity theory (and would be consistent with the earnings differentials across ethnic groups shown in Figure 19-8). Yet many people would still consider the resulting distribution of income unfair.

Still, many observers think that actual wage differentials cannot be entirely explained by compensating differentials, differences in talent, and differences in human capital. They believe that market power, efficiency wages, and discrimination also play an important role. We will examine these forces next.

Market Power

The marginal productivity theory of income distribution is based on the assumption that factor markets are perfectly competitive. In such markets we can expect workers to be paid the equilibrium value of their marginal product, regardless of who they are. But how valid is this assumption?

We studied markets that are not perfectly competitive in Chapters 13, 14, and 15; now let’s touch briefly on the ways in which labour markets may deviate from the competitive assumption.

Unions are organizations of workers that try to raise wages and improve working conditions for their members by bargaining collectively with employers.

One undoubted source of differences in wages between otherwise similar workers is the role of unions—organizations that try to raise wages and improve working conditions for their members. Labour unions, when they are successful, replace one-

Just as workers can sometimes organize to extract higher wages than they would otherwise receive, employers can sometimes organize to pay lower wages than would result from competition. For example, health care workers—

How much does collective action, either by workers or by employers, affect wages in Canada now? Canada’s unionization rates have remained relatively stable in the past few decades, falling only from 34% in 1997 to 31.2% in 2013. So unlike the United States, where less than 7% of private sector employees were unionized in 2010, unions in Canada still exert a significant upward effect on wages. In 2013 about 58% of all unionized employees worked in the public sector, balancing the market power governments possesses as employers. However, with deregulation, outsourcing, and globalization, the power of unions has eroded slightly, especially their bargaining power over wages. Nonetheless, they still play an important role in the negotiations of job security, better working conditions, and benefits for their members.

Efficiency Wages

A second source of wage inequality is the phenomenon of efficiency wages—a type of incentive scheme used by employers to motivate workers to work hard and to reduce worker turnover. Suppose a worker performs a job that is extremely important—

So a worker who happens to be observed performing poorly and is therefore fired is now worse off for having to accept a lower-

According to the efficiency-wage model, some employers pay an above-

The efficiency-wage model explains why we might observe wages offered above their equilibrium level. Like the price floors we studied in Chapter 5—and, in particular, much like the minimum wage—

As a result, two workers with exactly the same profile—

Discrimination

It is a real and ugly fact that throughout history there has been discrimination against workers who are considered to be of the wrong race, ethnicity, gender, or other characteristics. How does this fit into our economic models?

The main insight economic analysis offers is that discrimination is not a natural consequence of market competition. On the contrary, market forces tend to work against discrimination. To see why, consider the incentives that would exist if social convention dictated that women be paid, say, 30% less than men with equivalent qualifications and experience. A company whose management was itself unbiased would then be able to reduce its costs by hiring women rather than men—

But if market competition works against discrimination, how is it that so much discrimination has taken place? The answer is twofold. First, when labour markets don’t work well, employers may have the ability to discriminate without hurting their profits. For example, market interferences (such as unions or minimum-

In research published in the American Economic Review, two economists, Marianne Bertrand and Sendhil Mullainathan, documented discrimination in hiring by sending fictitious resumés to prospective employers on a random basis. Applicants with “white-

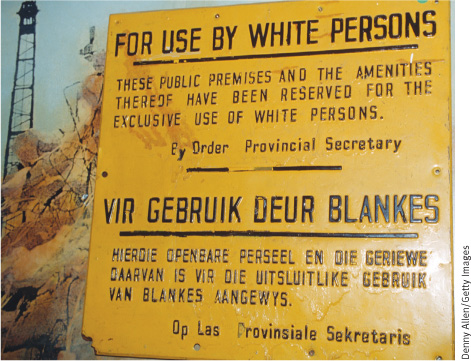

THE ECONOMICS OF APARTHEID

The Republic of South Africa is the richest nation in Africa, but it also has a harsh political history. Until the peaceful transition to majority rule in 1994, the country was controlled by its white minority, Afrikaners, who are the descendants of European (mainly Dutch) immigrants. This minority imposed an economic system known as apartheid, which overwhelmingly favoured white interests over those of native Africans and other groups considered “non-

The origins of apartheid go back to the early years of the twentieth century, when large numbers of white farmers began moving into South Africa’s growing cities. There they discovered, to their horror, that they did not automatically earn higher wages than other races. But they had the right to vote—

In other words, racial discrimination was possible because it was backed by the power of the government, which prevented markets from following their natural course.

In 1994, in one of the political miracles of modern times, the white regime ceded power and South Africa became a full-

Second, discrimination has sometimes been institutionalized in government policy. This institutionalization of discrimination has made it easier to maintain it against market pressure, and historically it is the form that discrimination has typically taken. For example, in Canada in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Asians faced immigration barriers (including exclusion from entry) and laws restricting the jobs they could have and forcing their wages to be less than what other employees earned. In the United States, African-

So Does Marginal Productivity Theory Work?

The main conclusion you should draw from this discussion is that the marginal productivity theory of income distribution is not a perfect description of how factor incomes are determined but that it works pretty well. The deviations are important. But, by and large, in a modern economy with well-functioning labour markets, factors of production are paid the equilibrium value of the marginal product—the value of the marginal product of the last unit employed in the market as a whole.

It’s important to emphasize, once again, that this does not mean that the factor distribution of income is morally justified.

MARGINAL PRODUCTIVITY AND THE “1%”

In the fall of 2011, there were widespread public demonstrations in the United States, Canada, and a number of other countries against the growing inequality of personal income. American protestors, known as the Occupy Wall Street movement, adopted the slogan “We are the 99%” to emphasize the fact that the incomes of the top 1% of the population had grown much faster than those of most Americans.

One year earlier, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives released a study on income inequality entitled The Rise of Canada’s Richest 1%. This study found that, between 1977 and 2007, high income Canadians captured an ever-growing share of all income. The richest 10% of all tax filers saw their share of total income rise by one seventh. The top 1% saw their share of income double, the richest 0.1% saw their share almost triple, and the richest 0.01% saw their share of total income more than quintuple. In fact, according to the study “Canada’s richest 1%—the 246 000 privileged few whose average income is $405 000 (in 2007)—took in almost a third (32%) of all growth in incomes in the fastest growing decade in this generation, 1997 to 2007.” In 2010, the top 1% had a median income that was about seven times the median income of all Canadians.

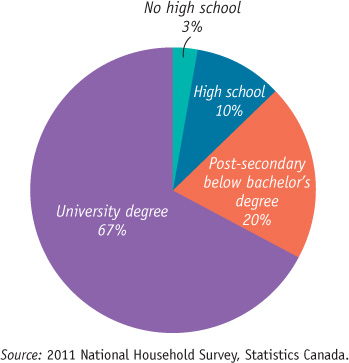

Why have the richest Canadians and Americans been pulling away from the rest? The short answer is that the causes are a source of considerable dispute and continuing research. One thing is clear, however: this aspect of growing inequality can’t be explained simply in terms of the growing demand for highly educated labour. In this chapter’s opening story, we pointed out that there has been a growing wage premium for workers with advanced degrees. Yet despite this growing premium, as Figure 19-10 shows, having an advanced degree only increases the likelihood of gaining access to the top 1% of all income earners. Having such a degree does not guarantee membership to this group, nor is having such a degree a necessary condition to gain entry to this exclusive club.

This doesn’t mean that the top 1% aren’t “earning” their incomes. It does show, however, that the explanation for their huge gains is not entirely education.

Quick Review

Existing large disparities in wages both among individuals and across groups lead some to question the marginal productivity theory of income distribution.

Compensating differentials, as well as differences in the values of the marginal products of workers that arise from differences in talent, job experience, and human capital, account for some wage disparities.

Market power, in the form of unions or collective action by employers, as well as the efficiency-wage model, in which employers pay an above-equilibrium wage to induce better performance, also explain how some wage disparities arise.

Discrimination has historically been a major factor in wage disparities. Market competition tends to work against discrimination. But discrimination can leave a long-lasting legacy of diminished human capital acquisition.

Check Your Understanding 19-3

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 19-3

Question 19.4

Assess each of the following statements. Do you think they are true, false, or ambiguous? Explain.

The marginal productivity theory of income distribution is inconsistent with the presence of income disparities associated with gender, ethnicity, or immigration status.

Companies that engage in workplace discrimination but whose competitors do not are likely to have lower profits as a result of their actions.

Workers who are paid less because they have less experience are not the victims of discrimination.

False. Income disparities associated with gender, ethnicity, or immigration status can be explained by the marginal productivity theory of income distribution provided that differences in marginal productivity across people are correlated with gender, ethnicity, or immigration status. One possible source for such correlation is past discrimination. Such discrimination can lower individuals’ marginal productivity by, for example, preventing them from acquiring the human capital that would raise their productivity. Another possible source of the correlation is differences in work experience that are associated with gender, ethnicity, or immigration status. For example, in jobs where work experience or length of tenure is important, women may earn lower wages because on average more women than men take child-care-related absences from work.

True. Companies that discriminate when their competitors do not are likely to hire less able workers because they discriminate against more able workers who are considered to be of the wrong gender, ethnicity, or other characteristic. And with less able workers, such companies are likely to earn lower profits than their competitors that don’t discriminate.

Ambiguous. In general, workers who are paid less because they have less experience may or may not be the victims of discrimination. The answer depends on the reason for the lack of experience. If workers have less experience because they are young or have chosen to do something else rather than gain experience, then they are not victims of discrimination if they are paid less. But if workers lack experience because previous job discrimination prevented them from gaining experience, then they are indeed victims of discrimination when they are paid less.