2.2 Using Models

Economics, we have now learned, is mainly a matter of creating models that draw on a set of basic principles but add some more specific assumptions that allow the modeller to apply those principles to a particular situation. But what do economists actually do with their models?

Positive versus Normative Economics

Imagine that you are an economic adviser to the premier of your province. What kinds of questions might the premier ask you to answer?

Well, here are three possible questions:

How much revenue will the provincial gasoline tax yield next year?

How much would that revenue increase if the tax were raised by 5 percentage points?

Should the government increase the tax, bearing in mind that the tax increase will raise much-

needed revenue and reduce traffic and air pollution, but will impose some financial hardship on frequent commuters and the trucking industry?

There is a big difference between the first two questions and the third one. The first two are questions about facts. Your forecast of next year’s gasoline tax will be proved right or wrong when the numbers actually come in. Your estimate of the impact of a change in the tax is a little harder to check—

But the question of whether the tax on gasoline should be raised may not have a “right” answer—

Positive economics is the branch of economic analysis that describes the way the economy actually works.

This example highlights a key distinction between two roles of economic analysis. Analysis that tries to answer questions about the way the world works, which have definite right and wrong answers, is known as positive economics. In contrast, analysis that involves saying how the world should work is known as normative economics. To put it another way, positive economics is about objective description; normative economics is about subjective prescription.

Normative economics makes prescriptions about the way the economy should work.

Positive economics occupies most of the time and effort of the economics profession. And models play a crucial role in almost all positive economics. As we mentioned earlier, the Canadian government uses computer models to assess proposed changes in federal tax policy, and many provincial and territorial governments have similar models to assess the effects of their own tax policies.

A forecast is a simple prediction of the future.

It’s worth noting that there is a subtle but important difference between the first and second questions we imagined the premier asking. Question 1 asked for a simple prediction about next year’s revenue—

The answers to such questions often serve as a guide to policy, but they are still predictions, not prescriptions. That is, they tell you what will happen if a policy is changed; they don’t tell you whether or not that result is good. Suppose your economic model tells you that the premier’s proposed increase in gasoline taxes will raise inner city property values but will hurt people who must use their cars to get to work. Does that make this proposed tax increase a good idea or a bad one? It depends on whom you ask. As we’ve just seen, someone who is very concerned about pollution will support the increase, but someone who is very concerned with the welfare of drivers will feel differently. That’s a value judgment—

Still, economists often do engage in normative economics and give policy advice. How can they do this when there may be no “right” answer?

One answer is that economists are also citizens, and we all have our opinions. But economic analysis can often be used to show that some policies are clearly better than others, regardless of anyone’s opinions.

Suppose that policies A and B achieve the same goal, but policy A makes everyone better off than policy B—

For example, two different policies have been used to help low-

When policies can be clearly ranked in this way, then economists generally agree. But it is no secret that economists sometimes disagree.

WHEN ECONOMISTS AGREE

“If all the economists in the world were laid end to end, they still couldn’t reach a conclusion.” So goes one popular economist joke. But do economists really disagree that much?

Not according to a classic survey of members of the American Economic Association, reported in the May 1992 issue of the American Economic Review. The authors asked respondents to agree or disagree with a number of statements about the economy; what they found was a high level of agreement among professional economists on many of the statements. At the top, with more than 90 percent of the economists agreeing, were “Tariffs and import quotas usually reduce general economic welfare” and “A ceiling on rents reduces the quantity and quality of housing available.” What’s striking about these two statements is that many non-

So is the stereotype of quarrelling economists a myth? Not entirely: economists do disagree quite a lot on some issues, especially in macroeconomics. But there is a large area of common ground.

When and Why Economists Disagree

Economists have a reputation for arguing with each other. Where does this reputation come from, and is it justified?

One important answer is that media coverage tends to exaggerate the real differences in views among economists. If nearly all economists agree on an issue—for example, the proposition that rent controls lead to housing shortages—reporters and editors are likely to conclude that it’s not a story worth covering, meaning that professional consensus tends to go unreported. But an issue on which prominent economists take opposing sides—for example, whether cutting taxes right now would help the economy—makes a news story worth reporting. So you hear much more about the areas of disagreement within economics than you do about the large areas of agreement.

It is also worth remembering that economics is, unavoidably, often tied up in politics. On a number of issues powerful interest groups know what opinions they want to hear; they therefore have an incentive to find and promote economists who profess those opinions, giving these economists a prominence and visibility out of proportion to their support among their colleagues.

While the appearance of disagreement among economists exceeds the reality, it remains true that economists often do disagree about important things. For example, some well-respected economists argue vehemently that the Canadian government should replace the income tax with a consumption tax. Other equally respected economists disagree. Why this difference of opinion?

One important source of differences lies in values: as in any diverse group of individuals, reasonable people can differ. In comparison to an income tax, a consumption tax typically falls more heavily on people of modest means. So an economist who values a society with more social and income equality for its own sake will tend to oppose a consumption tax. An economist with different values will be less likely to oppose it.

A second important source of differences arises from economic modelling. Because economists base their conclusions on models, which are simplified representations of reality, two economists can legitimately disagree about which simplifications are appropriate—and therefore arrive at different conclusions.

In 2009, British Columbia decided to harmonize its provincial sales tax with the federal Goods and Services Tax (GST) starting in 2010, only to return to the original system after the harmonized sales tax (HST) was defeated in a 2011 referendum. Suppose that two economists were asked for their opinion on the situation. Economist A may focus on the loss of provincial control over the design and collection of sales taxes or the additional sales tax now imposed on certain purchases.5 But economist B may think that the right way to approach the question is to ignore sovereignty and broadening of the sales tax base and focus on the ways in which the proposed law would change consumption behaviour and the ways in which firms conduct their businesses. This economist might point to studies suggesting that a harmonized sales tax lowers the cost of operating a business, lowers some prices, and promotes more business investment and job creation, all desirable results.

Because the economists have used different models—that is, made different simplifying assumptions about what is most important—they arrive at different conclusions. And so the two economists may find themselves on different sides of the issue.

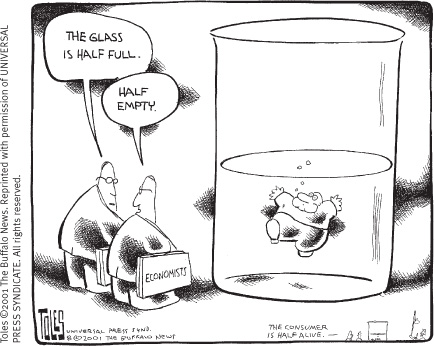

Behavioural economics, a relatively new approach to modelling that combines concepts from psychology and economics, also leads to different models, which can cause disagreement among economists. Traditional economic models assume that decision-makers are rational, unemotional, and capable of processing large amounts of information in order to make an optimal choice. Meanwhile, behavioural economics acknowledges that economic decision-makers are human beings who can be irrational, emotional, and may not learn from their mistakes. Some might say the traditional approach describes how the world should be (normative economics) while behavioural economics attempts to describe the world as it really is (positive economics).

Both methods of creating models help us better understand economic decisionmaking, but their differing assumptions can lead to very different results. In finance, for example, the traditional assumptions imply that agents learn from past mistakes and thus do not repeatedly make the same mistakes, resulting in very efficient financial markets, while in behavioural economic models irrational agents can make systematic errors, which can help explain the existence of stock market anomalies.

In most cases such disputes are eventually resolved by the accumulation of evidence showing which of the various models proposed by economists does a better job of fitting the facts. However, in economics, as in any science, it can take a long time before research settles important disputes—decades, in some cases. And since the economy is always changing, in ways that make old models invalid or raise new policy questions, there are always new issues on which economists disagree. The policy-maker must then decide which economist to believe.

The important point is that economic analysis is a method, not a set of conclusions.

ECONOMISTS, BEYOND THE IVORY TOWER

Many economists are mainly engaged in teaching and research. But quite a few economists have a more direct hand in events.

As described earlier in this chapter (For Inquiring Minds, “The Model That Ate the Economy”), one specific branch of economics, finance theory, plays an important role on Bay Street, Wall Street, and other financial centres around the world—not always to good effect. But pricing assets is by no means the only useful function economists serve in the business world. Businesses need forecasts of the future demand for their products, predictions of future raw-material prices, assessments of their future financing needs, and more; for all of these purposes, economic analysis is essential.

Some of the economists employed in the business world work directly for the institutions that need their input. Top financial institutions like Royal Bank and National Bank maintain high-quality economics groups, which produce analyses of forces and events likely to affect financial markets. Other economists are employed by consulting firms, which sell analysis and advice to a wide range of other businesses.

Last but not least, economists participate extensively in government. Indeed, government agencies at both federal and provincial levels are major employers of economists. This shouldn’t be surprising: one of the most important functions of government is to make economic policy, and almost every government policy decision must take economic effects into consideration. So governments around the world employ economists in a variety of roles.

You are likely to find economists working in almost every branch of the Canadian government. Consider the mandates of the departments dealing with Aboriginal affairs, agriculture, environment, immigration, interprovincial relations, natural resources, transportation, or science and technology! No matter what department comes to mind, there is a strong economic dimension involved. However, the strongest concentration of economists is likely to be found in the Department of Finance, which plans and prepares the federal government’s budget, and analyzes and designs tax policies. This department also develops policies on international finance and helps design Canada’s tariff policies. The Bank of Canada employs economists who help design monetary policy, implement that policy, and regulate chartered banks. And economists play an especially important role in two international organizations headquartered in Washington, D.C.: the International Monetary Fund, which provides advice and loans to countries experiencing economic difficulties, and the World Bank, which provides advice and loans to promote long-term economic development.

In the past, it wasn’t that easy to track what all these economists working on practical affairs were up to. These days, however, there is a very lively online discussion of economic prospects and policy, on websites that range from the home page of the International Monetary Fund (www.imf.org), to business-oriented sites like economy.com, to the blogs of individual economists, like that of Mark Thoma (economistsview.typepad.com) or, yes, our own blog, which is among the Technorati top 100 blogs, at krugman.blogs.nytimes.com.

Quick Review

Positive economics— the focus of most economic research—is the analysis of the way the world works, in which there are definite right and wrong answers. If often involves making forecasts. But in normative economics, which makes prescriptions about how things ought to be, there are often no right answers and only value judgments.

Economists do disagree—though not as much as legend has it—for two main reasons. One, they may disagree about which simplifications to make in a model. Two, economists may disagree—like everyone else—about values.

Check Your Understanding 2-2

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 2-2

Question 2.5

Which of the following statements is a positive statement? Which is a normative statement?

Society should take measures to prevent people from engaging in dangerous personal behaviour.

People who engage in dangerous personal behaviour impose higher costs on society through higher medical costs.

This is a normative statement because it stipulates what should be done. In addition, it may have no “right” answer. That is, should people be prevented from all dangerous personal behaviour if they enjoy that behaviour—like skydiving? Your answer will depend on your point of view.

This is a positive statement because it is a description of fact.

Question 2.6

True or false? Explain your answer.

Policy choice A and policy choice B attempt to achieve the same social goal. Policy choice A, however, results in a much less efficient use of resources than policy choice B. Therefore, economists are more likely to agree on choosing policy choice B.

When two economists disagree on the desirability of a policy, it’s typically because one of them has made a mistake.

Policy-makers can always use economics to figure out which goals a society should try to achieve.

True. Economists often have different value judgments about the desirability of a particular social goal. But despite those differences in value judgments, they will tend to agree that society, once it has decided to pursue a given social goal, should adopt the most efficient policy to achieve that goal. Therefore economists are likely to agree on adopting policy choice B.

False. Disagreements between economists are more likely to arise because they base their conclusions on different models or because they have different value judgments about the desirability of the policy.

False. Deciding which goals a society should try to achieve is a matter of value judgments, not a question of economic analysis.

Efficiency, Opportunity Cost, and the Logic of Lean Production

In the summer and fall of 2010, workers were rearranging the furniture in Boeing’s final assembly plant in Everett, Washington, in preparation for the production of the Boeing 767. It was a difficult and time-consuming process, however, because the items of “furniture”—Boeing’s assembly equipment—weighed on the order of 180 tonnes each. It was a necessary part of setting up a production system based on “lean manufacturing,” also called “just-in-time” production. Lean manufacturing, pioneered by Toyota Motors of Japan, is based on the practice of having parts arrive on the factory floor just as they are needed for production. This reduces the amount of parts Boeing holds in inventory as well as the amount of the factory floor needed for production—in this case, reducing the space required for manufacture of the 767 by 40%.

Boeing had adopted lean manufacturing in 1999 in the manufacture of the 737, the most popular commercial airplane. By 2005, after constant refinement, Boeing had achieved a 50% reduction in the time it takes to produce a plane and a nearly 60% reduction in parts inventory. An important feature is a continuously moving assembly line, moving products from one assembly team to the next at a steady pace and eliminating the need for workers to wander across the factory floor from task to task or in search of tools and parts.

Toyota’s lean production techniques have been the most widely adopted of all manufacturing techniques and have revolutionized manufacturing worldwide. In simple terms, lean production is focused on organization and communication. Workers and parts are organized so as to ensure a smooth and consistent workflow that minimizes wasted effort and materials. Lean production is also designed to be highly responsive to changes in the desired mix of output—for example, quickly producing more sedans and fewer minivans according to changes in customers’ demands.

Toyota’s lean production methods were so successful that they transformed the global auto industry and severely threatened once-dominant North American automakers. Until the 1980s, the “Big Three”—Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors—dominated the North American auto industry. In the 1980s, however, Toyotas became increasingly popular in North America due to their high quality and relatively low price—so popular that the Big Three eventually prevailed upon the U.S. government to protect them by restricting the sale of Japanese autos in the United States. A few months later, the Canadian government set a limit on the number of cars Toyota could export to Canada. Over time, Toyota responded by building assembly plants in the United States and in Canada, bringing along its lean production techniques, which then spread throughout North American manufacturing. Toyota’s growth continued, and by 2008 it had eclipsed General Motors as the largest automaker in the world.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 2.7

What is the opportunity cost associated with having a worker wander across the factory floor from task to task or in search of tools and parts?

Question 2.8

Explain how lean manufacturing improves the economy’s efficiency in production and consumption.

Question 2.9

Before lean manufacturing innovations, Japan mostly sold consumer electronics to Canada and the United States. How did lean manufacturing innovations alter Japan’s comparative advantage vis-à-vis North America?

Question 2.10

Predict how the shift in the location of Toyota’s production from Japan to North America is likely to alter the pattern of comparative advantage in automaking between the two regions.