6.1 Defining and Measuring Elasticity

Most Canadians don’t have to pay for a flu shot, although we do pay for some other types of vaccinations, such as the Hepatitis B vaccine. However, it is not uncommon for residents of other countries, such as the United States, to have to pay for their flu shots. So, what if individual Canadians did have to pay for flu vaccines? In order for Flunomics, a hypothetical flu vaccine distributor, to know whether it could raise its revenue by significantly raising the price of its flu vaccine when it was most needed, it would have to know the price elasticity of demand for flu vaccinations.

Calculating the Price Elasticity of Demand

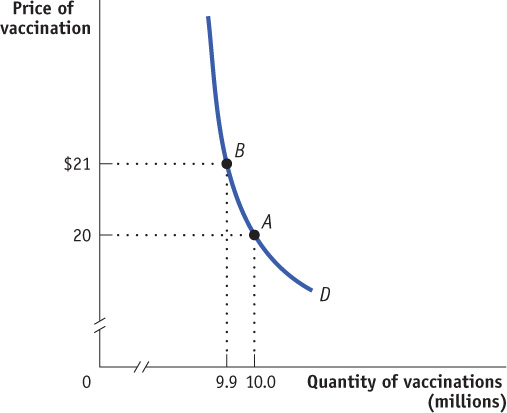

Figure 6-1 shows a hypothetical demand curve for flu vaccinations. At a price of $20 per vaccination, consumers would demand 10 million vaccinations per year (point A); at a price of $21, the quantity demanded would fall to 9.9 million vaccinations per year (point B).

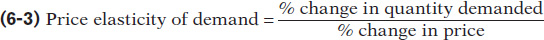

Figure 6-1, then, tells us the change in the quantity demanded for a particular change in the price. But how can we turn this into a measure of price responsiveness? The answer is to calculate the price elasticity of demand, also known as the own price elasticity of demand because it relates the change in the quantity demanded of a product to a change in its own price (as opposed to the prices of other products).

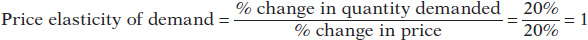

The price elasticity of demand is the ratio of the percentage change in the quantity demanded to the percentage change in the price as we move along the demand curve. (Given the demand is normally downward sloping, when interpreting the price elasticity of demand, we only look at the absolute value.)

The price elasticity of demand is the ratio of the percentage change in quantity demanded to the percentage change in price as we move along the demand curve. As we’ll see later in this chapter, the reason economists use percentage changes is to obtain a measure that doesn’t depend on the units in which a good is measured (say, a child-

To calculate the price elasticity of demand, we first calculate the percentage change in the quantity demanded and the corresponding percentage change in the price as we move along the demand curve. These are defined as follows:

and

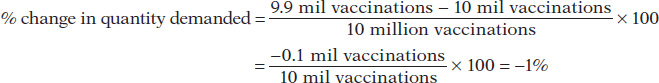

In Figure 6-1, we see that when the price rises from $20 to $21, the quantity demanded falls from 10 million to 9.9 million vaccinations, yielding a change in the quantity demanded of 0.1 million vaccinations. So the percentage change in the quantity demanded is

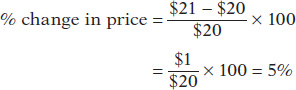

The initial price is $20 and the change in the price is $1, so the percentage change in price is

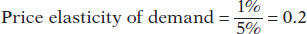

To calculate the price elasticity of demand, we find the ratio of the percentage change in the quantity demanded to the percentage change in the price:

In Figure 6-1, the price elasticity of demand1 is therefore

The law of demand says that demand curves are downward sloping, so price and quantity demanded always move in opposite directions. In other words, a positive percentage change in price (a rise in price) leads to a negative percentage change in the quantity demanded; a negative percentage change in price (a fall in price) leads to a positive percentage change in the quantity demanded. This means that the price elasticity of demand is, in strictly mathematical terms, a negative number. However, it is inconvenient to repeatedly write a minus sign. So when economists talk about the price elasticity of demand, they usually drop the minus sign and report the absolute value of the price elasticity of demand. In this case, for example, economists would usually say “the price elasticity of demand is 0.2,” taking it for granted that you understand they mean minus 0.2. We follow this convention here.

The larger the price elasticity of demand, the more responsive the quantity demanded is to the price. When the price elasticity of demand is large—

As we’ll see shortly, a price elasticity of 0.2 indicates a small response of quantity demanded to price. That is, the quantity demanded will fall by a relatively small amount when price rises. This is what economists call inelastic demand. And inelastic demand is exactly what Flunomics needed for its strategy to increase revenue by raising the price of its flu vaccines.

An Alternative Way to Calculate Elasticities: The Midpoint Method

Price elasticity of demand compares the percentage change in quantity demanded with the percentage change in price. When we look at some other elasticities, which we will do shortly, we’ll learn why it is important to focus on percentage changes. But at this point we need to discuss a technical issue that arises when you calculate percentage changes in variables.

The best way to understand the issue is with a real example. Suppose you were trying to estimate the price elasticity of demand for gasoline by comparing gasoline prices and consumption in different countries. Because of higher taxes, gasoline usually costs more in Canada than in the United States (approximately thirty cents more per litre in 2013). So what is the percentage difference between Canadian and American gas prices?

Well, it depends on which way you measure it. In 2013, the average price of a litre of gas in Canada was about $1.23 while the average price of a litre of gas in the United States was closer to $0.91. Because the price of a litre of gas in Canada was $0.32 higher than in the United States, it was 35% ($0.32/$0.91 × 100%) higher. Because the price of gasoline in the United States was $0.32 lower, it was 26% ($0.32/$1.23 × 100%) lower.

This is a nuisance: we’d like to have a percentage measure of the difference in prices that doesn’t depend on which way you measure it. To avoid computing different elasticities for rising and falling prices we use the midpoint method.

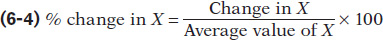

The midpoint method replaces the usual definition of the percentage change in a variable, X, with a slightly different definition:

The midpoint method is a technique for calculating the percentage change. In this approach, we calculate changes in a variable compared with the average, or midpoint, of the starting and final values.

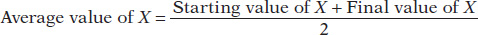

where the average value of X is defined as

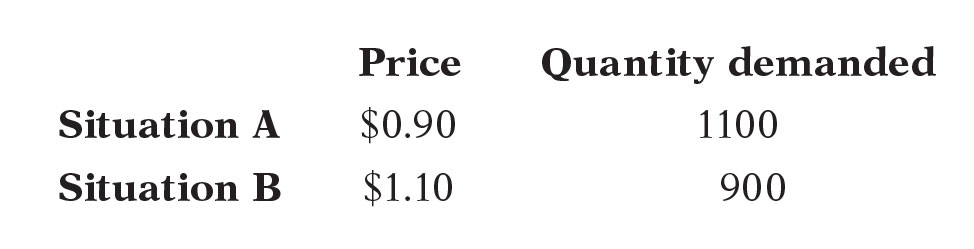

When calculating the price elasticity of demand using the midpoint method, both the percentage change in the price and the percentage change in the quantity demanded are found using this method. To see how this method works, suppose you have the following data for some good:

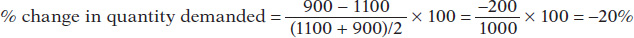

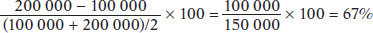

To calculate the percentage change in quantity going from situation A to situation B, we compare the change in the quantity demanded—a fall of 200 units—with the average of the quantity demanded in the two situations. So we calculate

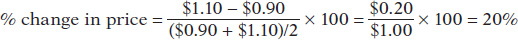

In the same way, we calculate

So in this case we would calculate the price elasticity of demand to be

again dropping the minus sign.

The important point is that we would get the same result, a price elasticity of demand of 1, whether we go up the demand curve from situation A to situation B or down from situation B to situation A.

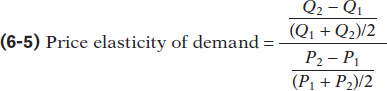

To arrive at a more general formula for price elasticity of demand, suppose that we have data for two points on a demand curve. At point 1 the quantity demanded and price are (Q1, P1); at point 2 they are (Q2, P2). Then the formula for calculating the price elasticity of demand is:

As before, when finding a price elasticity of demand calculated by the midpoint method, we drop the minus sign and use the absolute value.

ESTIMATING ELASTICITIES

You might think it’s easy to estimate price elasticities of demand from real-world data: just compare percentage changes in prices with percentage changes in quantities demanded. Unfortunately, it’s rarely that simple because changes in price aren’t the only thing affecting changes in the quantity demanded: other factors—such as changes in income, changes in tastes, and changes in the prices of other goods—shift the demand curve, thereby changing the quantity demanded at any given price. To estimate price elasticities of demand, economists must use careful statistical analysis to separate the influence of these different factors, holding other things equal.

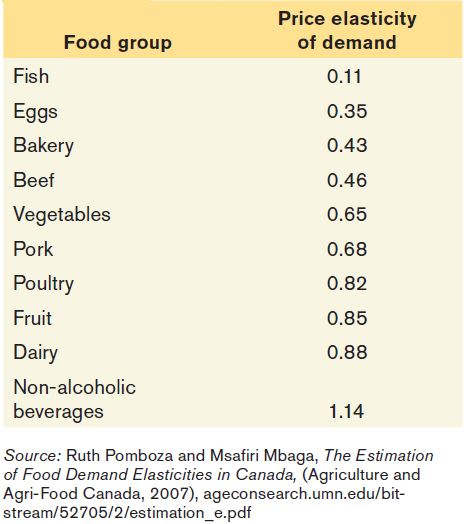

In 2007, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada released a report on the estimated demand elasticities for food in Canada. The study aggregated 246 food categories in the Food Expenditure Survey (FOODEX) into 14 food groups. The price elasticities of some of the selected food groups are ranked in ascending order in Table 6-1.

You may notice that the price elasticity of demand varies across food groups. With the exception of non-alcoholic beverages, the price elasticities of demand in Table 6-1 are less than 1. In economics, we say that these goods have inelastic demand. The price elasticity of non-alcoholic beverages is greater than 1; we say that the demand for non-alcoholic beverages is elastic. We’ll explain in the next section the difference between inelastic demand and elastic demand.

Quick Review

The price elasticity of demand is equal to the percentage change in the quantity demanded divided by the percentage change in the price as you move along the demand curve, dropping any minus sign.

In practice, percentage changes are best measured using the midpoint method, in which the percentage change in each variable is calculated using the average of starting and final values.

Check Your Understanding 6-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 6-1

Question 6.1

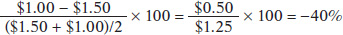

The price of strawberries falls from $1.50 to $1.00 per carton and the quantity demanded goes from 100 000 to 200 000 cartons. Use the midpoint method to find the price elasticity of demand.

By the midpoint method, the percentage change in the price of strawberries is

Similarly, the percentage change in the quantity of strawberries demanded is

Dropping the minus sign, the price elasticity of demand using the midpoint method is 67%/40% = 1.7.

Question 6.2

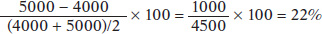

At the present level of consumption, 4000 movie tickets, and at the current price, $5 per ticket, the price elasticity of demand for movie tickets is 1. Using the midpoint method, calculate the percentage by which the owners of movie theatres must reduce price in order to sell 5000 tickets.

By the midpoint method, the percentage change in the quantity of movie tickets demanded in going from 4000 tickets to 5000 tickets is

Since the price elasticity of demand is 1 at the current consumption level, it will take a 22% reduction in the price of movie tickets to generate a 22% increase in quantity demanded.

Question 6.3

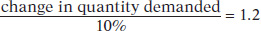

The price elasticity of demand for ice -cream sandwiches is 1.2 at the current price of $0.50 per sandwich and the current consumption level of 100 000 sandwiches. Calculate the change in the quantity demanded when price rises by $0.05. Use Equations 6-1 and 6-2 to calculate percentage changes and Equation 6-3 to relate price elasticity of demand to the percentage changes.

Since price rises, we know that quantity demanded must fall. Given the current price of $0.50, a $0.05 increase in price represents a 10% change, using the method in Equation 6-2. So the price elasticity of demand is

so that the percentage change in quantity demanded is 12%. A 12% decrease in quantity demanded represents 100 000 × 0.12, or 12 000 sandwiches.