7.4 Understanding the Tax System

An excise tax is the easiest tax to analyze, making it a good vehicle for understanding the general principles of tax analysis. However, in Canada today, excise taxes are actually a relatively minor source of government revenue. In this section, we develop a framework for understanding more general forms of taxation and look at some of the major taxes used in Canada.

Tax Bases and Tax Structure

The tax base is the measure or value, such as income or property value, that determines how much tax an individual or firm pays.

Every tax consists of two pieces: a base and a structure. The tax base is the measure or value that determines how much tax an individual or firm pays. It is usually a monetary measure, like income or property value. The tax structure specifies how the tax depends on the tax base. It is usually expressed in percentage terms; for example, homeowners in some areas might pay yearly property taxes equal to 2% of the value of their homes.

The tax structure specifies how the tax depends on the tax base.

Some important taxes and their tax bases are as follows:

An income tax is a tax on an individual’s or family’s income.

Income tax: a tax that depends on the income of an individual or family from wages and investments (also known as the personal income tax)

A payroll tax is a tax on the earnings an employer pays to an employee.

Payroll tax: a tax that depends on the earnings an employer pays to an employee

A sales tax is a tax on the value of goods sold.

Sales tax: a tax that depends on the value of goods sold (also known as an excise tax)

A profits tax is a tax on a firm’s profits.

Profits tax: a tax on an incorporated firm’s profits (also known as the corporate income tax)

A property tax is a tax on the value of property, such as the value of a home.

Property tax: a tax that depends on the value of property, such as the value of a home

A wealth tax is a tax on an individual’s wealth.

Wealth tax: a tax on an individual’s wealth

A proportional tax is the same percentage of the tax base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth.

Once the tax base has been defined, the next question is how the tax depends on the base. The simplest tax structure is a proportional tax, also sometimes called a flat tax, which is the same percentage of the base regardless of the taxpayer’s income or wealth. For example, a property tax that is set at 2% of the value of the property, whether the property is worth $10 000 or $10 000 000, is a proportional tax. Many taxes, however, are not proportional. Instead, different people pay different percentages, usually because the tax law tries to take account of either the benefits principle or the ability-

A progressive tax takes a larger share of the income of high-

Because taxes are ultimately paid out of income, economists classify taxes according to how they vary with the income of individuals. A tax that rises more than in proportion to income, so that high-

A regressive tax takes a smaller share of the income of high-

The Canadian tax system contains a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes, though it is somewhat progressive overall.

Equity, Efficiency, and Progressive Taxation

Most, though not all, people view a progressive tax system as fairer than a regressive system. The reason is the ability-

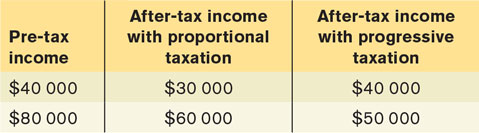

To see why, consider a hypothetical example, illustrated in Table 7-3. We assume that there are two kinds of people in the nation of Taxmania: half of the population earns $40 000 a year and half earns $80 000, so the average income is $60 000 a year. We also assume that the Taxmanian government needs to collect one-

One way to raise this revenue would be through a proportional tax that takes one-

Even this system might have some negative effects on incentives. Suppose, for example, that finishing college improves a Taxmanian’s chance of getting a higher-

But a strongly progressive tax system could create a much bigger incentive problem. Suppose that the Taxmanian government decided to exempt the poorer half of the population from all taxes but still wanted to raise the same amount of revenue. To do this, it would have to collect $30 000 from each individual earning $80 000 a year. As the third column of Table 7-3 shows, people earning $80 000 would then be left with income after taxes of $50 000—only $10 000 more than the after-

The marginal tax rate is the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away.

The point here is that any income tax system will tax away part of the gain an individual gets by moving up the income scale, reducing the incentive to earn more. But a progressive tax takes away a larger share of the gain than a proportional tax, creating a more adverse effect on incentives. In comparing the incentive effects of tax systems, economists often focus on the marginal tax rate: the percentage of an increase in income that is taxed away. In this example, the marginal tax rate on income above $40 000 is 25% with proportional taxation but 75% with progressive taxation.

Our hypothetical example is much more extreme than the reality of progressive taxation in Canada today—

Taxes in Canada

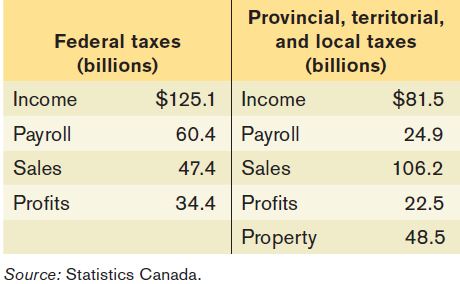

Table 7-4 shows the revenue raised by major taxes in Canada in 2012. Some of the taxes are collected by the federal government and the others by provincial, territorial, and local governments.

There is a major tax corresponding to five of the six tax bases we identified earlier. There are income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, profits taxes, and property taxes, all of which play an important role in the overall tax system. The only item missing is a wealth tax. In fact, most Canadian provinces and territories do have a wealth tax, called probate fees, which depends on the value of someone’s estate at the time of his or her death.

Probate fees are charged by the provincial court to recognize the validity of a deceased person’s will and the appointment of the executor. When the court grants letters of probate this notifies the public that the will is adequate and that it was not being challenged. Thus probate protects the executor and all parties who received an inheritance payment under the will from future legal challenges or claims. These fees vary significantly from province to province, in Quebec probate costs about $100 while in Ontario probate fees depend on the size of the estate rising to 15% of the value of the estate above $50 000. The deceased’s assets are deemed to have been sold on the day of the death, and any tax owing from this sale is payable through the regular income tax system on a final tax return. There is one important exception when someone dies: the assets can be passed, tax free, to a spouse.

In addition to the taxes shown in Table 7-4, provincial and local governments collect substantial revenue from other sources as varied as driver’s licence fees and sewer charges. These fees and charges are an important part of the tax burden but very difficult to summarize or analyze.

Are the taxes in Table 7-4 progressive or regressive? It depends on the tax. The personal income tax is strongly progressive. Payroll taxes, except for the CPP and EI portions paid only on earnings up to about $50 000, are somewhat regressive. Sales taxes are generally regressive, because higher-

Property taxes, which together with sales taxes represent the largest source of revenue for provincial, territorial, and local governments, are somewhat regressive. In addition, those other taxes principally levied at the provincial and local level are typically quite regressive: it costs the same amount to renew a driver’s licence or pay your vehicle licensing fee no matter what your income is.

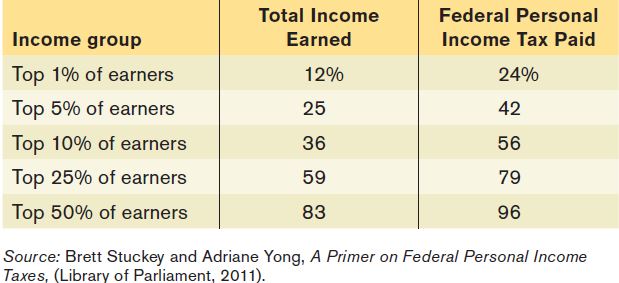

Overall, the federal income tax is quite progressive. The second column of Table 7-5 shows the share of all income earned by different percentiles of income earners. The third column of this table shows that as we move higher up the income distribution the share of federal income tax paid declines more slowly than the share of income earned does. In 2011, the people in the top half of the income distribution earned 83% of all income earned but paid 96% of federal income tax. The table shows that the federal tax income is indeed progressive, with low-

Since the mid-

And the overall tax system is likely even less progressive than in the past. The reduction of the GST from 7% to 5% helped make the tax system less regressive (or more progressive). But, increases in payroll tax rates and other fees charged by governments make the tax system more regressive. Also, corporate tax rates have fallen very significantly since the mid-

In summary, the Canadian tax system is somewhat progressive, with the richest tenth of the population paying a somewhat higher share of income in taxes than families in the middle, and the poorest Canadians paying considerably less. Although our tax system is progressive, the degree of progressiveness varies with the nature of the taxes. The federal income tax is more progressive than payroll taxes. And personal income taxation is more progressive than sales and property taxes.

YOU THINK YOU PAY HIGH TAXES?

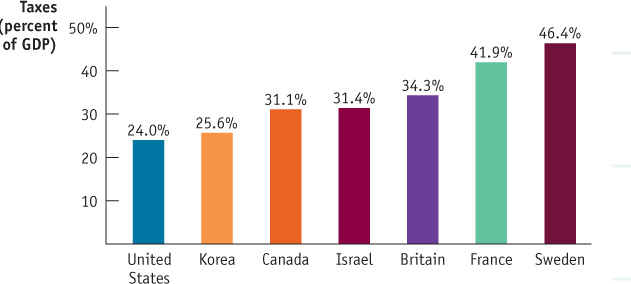

Everyone, everywhere complains about taxes. But citizens of Canada actually have less to complain about than citizens of most other wealthy countries.

To assess the overall level of taxes, economists usually calculate taxes as a share of gross domestic product—the total value of goods and services produced in a country. By this measure, as you can see in the accompanying figure, in 2009, Canadian taxes were near the middle of the scale. Our neighbour the United States has a significantly lower overall tax burden. But tax rates in Europe, where governments need a lot of revenue to pay for extensive benefits such as guaranteed health care and generous unemployment benefits, are up to 50% higher than in Canada.

Source: OECD.

TAXING INCOME VERSUS TAXING CONSUMPTION

The Canadian government taxes people mainly on the money they make, and less so on the money they spend on consumption. Yet most tax experts argue that this policy badly distorts incentives. Someone who earns income and then invests that income for the future gets taxed twice: once on the original sum and again on any earnings made from the investment. So a system that taxes income rather than consumption discourages people from saving and investing, instead it provides an incentive to spend their income today. And encouraging saving and investing is an important policy goal, both because empirical data show that Canadians tend to save too little for retirement and health expenses in their later years and because saving and investing contribute to economic growth.

Moving from a system that taxes income to one that taxes consumption could solve this problem. In fact, the governments of many countries get much of their revenue from a value-

Canada has taken mixed steps towards taxing consumption instead of income. The introduction of tax-

Value-

Different Taxes, Different Principles

Why are some taxes progressive but others regressive? Can’t the government make up its mind?

There are two main reasons for the mixture of regressive and progressive taxes in the Canadian system: the difference between levels of government and the fact that different taxes are based on different principles.

Provincial and especially local governments generally do not make as much effort to apply the ability-to-pay principle. This is largely because they are subject to tax competition: a province or local government that imposes high taxes on people with high incomes faces the prospect that those people may move to other locations where taxes are lower. This is much less of a concern at the national level, although a handful of very rich people have given up their Canadian citizenship to avoid paying Canadian taxes.

Although the federal government is in a better position than provincial or local governments to apply principles of fairness, it applies different principles to different taxes. We saw an example of this in the preceding Economics in Action. The most important tax, the federal income tax, is strongly progressive, reflecting the ability-to-pay principle. But the federal payroll taxes, the second most important tax, are somewhat regressive, because most of this tax revenue is linked to specific programs—Canada Pension Plan and Employment Insurance—and, reflecting the benefits principle, payroll taxes are levied more or less in proportion to the benefits received from these programs.

THE TOP MARGINAL INCOME TAX RATE

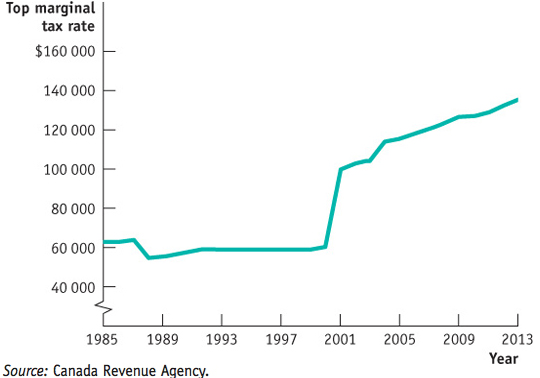

The amount of money a Canadian owes in federal income taxes is found by applying marginal tax rates on successively higher “brackets” of income. For example, in 2013 a single person would have paid 15% on the first $43 561 of taxable income (i.e., income after subtracting exemptions and deductions); 22% on the next $43 562; 26% on the next $47 931; and a top rate of 29% on his or her income, if any, over $135 054. Relatively few people (less than 5% of taxpayers) have incomes high enough to pay the top marginal rate. In fact, about 90% of Canadians pay no income tax or they fall into one of the first two bracket. But the top marginal income tax rate is often viewed as a useful indicator of the progressivity of the tax system, because it shows just how high a tax rate the Canadian government is willing to impose on the affluent.

While the top marginal tax rate is interesting, almost equally important is the taxable income cut-off where this rate begins to apply. Figure 7-11 shows the level of taxable income where the top federal tax bracket starts from 1985 to 2013. In each of these years any taxable income earned above this limit faced the highest marginal income tax rate. According to the Canadian Tax Foundation, the top combined federal and provincial marginal income tax rate in 1949 was 84%, and in 1971 it was 80% (both on taxable income above $400 000); in 1972 it was 59.93% (on taxable income above $60 000); in 1986 it was 53.38%; in 1987 it was 51.07%; in 1994 it was 46.4%. This is where it has pretty much stayed since. But the tax rate is only part of the story, the tax base matters, too. For example, the 1981 federal budget lowered personal tax rates and broadened the tax base. The 1987 budget lowered rates and broadened the base further, including converting tax deductions into tax credits. So Canada moved from a country with high rates and a narrow base to one with lower rates and a much broader tax base.

Quick Review

Every tax consists of a tax base and a tax structure.

Among the types of taxes are income taxes, payroll taxes, sales taxes, profits taxes, property taxes, and wealth taxes.

Tax systems are classified as being proportional, progressive, or regressive.

Progressive taxes are often justified by the ability-to-pay principle. But strongly progressive taxes lead to high marginal tax rates, which create major incentive problems.

Canada has a mixture of progressive and regressive taxes. However, the overall structure of taxes is progressive.

Check Your Understanding 7-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 7-4

Question 7.9

An income tax taxes 1% of the first $10 000 of income and 2% on all income above $10 000.

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $5000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

What is the marginal tax rate for someone with income of $20 000? How much total tax does this person pay? How much is this as a percentage of his or her income?

Is this income tax proportional, progressive, or regressive?

The marginal tax rate for someone with income of $5000 is 1%: for each additional $1 in income, $0.01 or 1%, is taxed away. This person pays total tax of $5000 × 1% = $50, which is ($50/$5000) × 100 = 1% of his or her income.

The marginal tax rate for someone with income of $20 000 is 2%: for each additional $1 in income, $0.02 or 2%, is taxed away. This person pays total tax of $10 000 × 1% + $10 000 × 2% = $300, which is ($300/$20 000) × 100 = 1.5% of his or her income.

Since the high-income taxpayer pays a larger percentage of his or her income than the low-income taxpayer, this tax is progressive.

Question 7.10

When comparing households at different income levels, economists find that consumption spending grows more slowly than income. Assume that when income grows by 50%, from $10 000 to $15 000, consumption grows by 25%, from $8000 to $10 000. Compare the percent of income paid in taxes by a family with $15 000 in income to that paid by a family with $10 000 in income under a 1% tax on consumption purchases. Is this a proportional, progressive, or regressive tax?

A 1% tax on consumption spending means that a family earning $15 000 and spending $10 000 will pay a tax of 1% × $10 000 = $100, equivalent to 0.67% of its income; ($100/$15 000) × 100 = 0.67%. But a family earning $10 000 and spending $8000 will pay a tax of 1% × $8000 = $80, equivalent to 0.80% of its income; ($80/$10 000) × 100 = 0.80%. So the tax is regressive, since the lower-income family pays a higher percentage of its income in tax than the higher-income family.

Question 7.11

True or false? Explain your answers.

Payroll taxes do not affect a person’s incentive to take a job because they are paid by employers.

A lump-sum tax is a proportional tax because it is the same amount for each person.

False. Recall that a seller always bears some burden of a tax as long as his or her supply of the good is not perfectly elastic. Since the supply of labour a worker offers is not perfectly elastic, some of the payroll tax will be borne by the worker, and therefore the tax will affect the person’s incentive to take a job.

False. Under a proportional tax, the percentage of the tax base is the same for everyone. Under a lump-sum tax, the total tax paid is the same for everyone, regardless of their income. A lump-sum tax is regressive.

Cross-Border Taxing

The rules for collecting taxes in Canada are relatively straightforward. When you buy something online from a Canadian retailer, you are charged the sales tax for your province or territory. It does not matter where in Canada the item is coming from, the shipping address determines the taxes. Similarly, you are expected to pay sales tax on major purchases from outside of Canada. The company shipping the item is in charge of collecting the proper sales tax, and generally charges their own brokerage fee for doing it.

Online shoppers in the United States have a different experience. According to the law, online retailers that don’t have a physical presence in a given state can sell products in that state without collecting sales tax. (The tax is still due, but residents are supposed to report the transaction and pay the tax themselves—a fact overlooked by online customers.) Sales tax is levied on transactions of most nonessential goods and services in 45 U.S. states (the exceptions are Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon), with the average sales tax bite being about 8% of the purchase price.

So, for example, if you compare the final price of An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth by Chris Hadfield, shipped to Florida, the Amazon.com price is lower than the BarnesandNoble.com price. The difference between the two prices is the 6% Florida sales tax added to the final price by BarnesandNoble.com; Amazon doesn’t collect the tax on its orders to Florida.

In fact, Amazon collects sales tax only in states where it has a retail or corporate presence, and the advantage for Amazon in the United States is that it has a physical presence in very few states—only Kansas, Kentucky, New York, North Dakota, and Washington. Amazon has also adopted a strategy of tax minimization, often taking extreme measures, such as forbidding employees to work or even send emails while in certain states to avoid the possibility of triggering state tax levies. In response to a tough new tax law in California, in 2011 Amazon terminated its joint advertising program with 25 000 California affiliates.

In contrast, the brick-and-mortar retailer Barnes and Noble, the parent company of BarnesandNoble.com, has bookstores in every state. (A brick-and-mortar retailer is one that has a physical store.) As a result, BarnesandNoble.com is compelled to collect sales tax on its online orders.

As reported in the Wall Street Journal, interviews and company documents have shown that Amazon believes that its tax policy is crucial to its success. It has been estimated that Amazon would have lost as much as $653 million in sales in 2011, or 1.4% of its annual revenue, if forced to collect sales tax. But its ability to avoid collecting sales tax is coming under assault by state tax authorities, hungry for new revenue during tough economic times. For example, Texas, where Amazon has a warehouse but no retail store, has only recently been able to force it to begin collecting state sales tax. And authorities in California have been arguing that Amazon should have to collect state sales tax there because it has affiliated vendors located in the state. In these and other cases, Amazon is fighting vigorously to retain its right not to collect U.S. sales tax. Now this may finally be coming to an end as a group of U.S. Members of Congress have proposed a new bill called the Marketplace Fairness Act, which is meant to level the playing field between online businesses that do not currently have to charge sales taxes and local brick-and-mortar stores that do. This bill, if enacted into law, would let individual U.S. states decide whether or not to have the (out-of-state) businesses collect and report sales taxes for Internet purchases, or to continue to leave it up to the consumers to report their purchases. And it’s not hard to guess which side BarnesandNoble.com is on.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 7.12

What effect do you think the difference in state sales tax collection has on Amazon’s sales versus BarnesandNoble.com’s sales?

Question 7.13

Suppose, as proposed by the Marketplace Fairness Act, sales tax is collected on all online books sales in the United States. From the evidence in this case, what do you think is the incidence of the tax between seller and buyer? What does this imply about the elasticity of supply of books by book retailers? (Hint: Compare the pre-tax prices of the book.)

Question 7.14

How do you think Amazon’s tax strategy has distorted its business behaviour? What tax policy would eliminate those distortions?