9.1 Costs, Benefits, and Profits

In making any type of decision, it’s critical to define the costs and benefits of that decision accurately. If you don’t know the costs and benefits, it is nearly impossible to make a good decision. So that is where we begin.

An important first step is to recognize the role of opportunity cost, a concept we first encountered in Chapter 1, where we learned that opportunity costs arise because resources are scarce. Because resources are scarce, the true cost of anything is what you must give up to get it—

Whether you decide to continue in school for another year or leave to find a job, each choice has costs and benefits. Because your time—

When making decisions, it is crucial to think in terms of opportunity cost, because the opportunity cost of an action is often considerably more than the cost of any outlays of money. Economists use the concepts of explicit costs and implicit costs to compare the relationship between opportunity costs and monetary outlays. We’ll discuss these two concepts first. Then we’ll define the concepts of accounting profit and economic profit, which are ways of measuring whether the benefit of an action is greater than the cost. Armed with these concepts for assessing costs and benefits, we will be in a position to consider our first principle of economic decision making: how to make “either–

Explicit versus Implicit Costs

Suppose that, after graduating from college or university, you have two options: to go to school for an additional year to get an advanced degree or to take a job immediately. You would like to enrol in the extra year in school but are concerned about the cost.

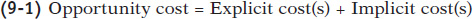

What exactly is the cost of that additional year of school? Here is where it is important to remember the concept of opportunity cost: the cost of the year spent getting an advanced degree includes what you forgo by not taking a job for that year. The opportunity cost of an additional year of school, like any cost, can be broken into two parts: the explicit cost of the year’s schooling and the implicit cost.

An explicit cost is a cost that requires an outlay of money. For example, the explicit cost of the additional year of schooling includes tuition. An implicit cost, though, does not involve an outlay of money; instead, it is measured by the value, in dollar terms, of the benefits that are forgone. For example, the implicit cost of the year spent in school includes the income you would have earned if you had taken a job instead:

An explicit cost is a cost that requires an outlay of money.

An implicit cost does not require an outlay of money; it is measured by the value, in dollar terms, of benefits that are forgone.

A common mistake, both in economic analysis and in life—

Table 9-1 gives a breakdown of hypothetical explicit and implicit costs associated with spending an additional year in school instead of taking a job. The explicit cost consists of tuition, books, supplies, and a computer for doing assignments—

A slightly different way of looking at the implicit cost in this example can deepen our understanding of opportunity cost. The forgone salary is the cost of using your own resources—

Understanding the role of opportunity costs makes clear the reason for the surge in school applications in 2009 and 2010: a rotten job market. Starting in the fall of 2008, the Canadian job market deteriorated sharply as the economy entered a severe recession. By 2010, the job market was still quite weak; although job openings had begun to reappear, a relatively high proportion of those openings were for jobs with low wages and no benefits. As a result, the opportunity cost of another year of schooling had declined significantly, making spending another year at school a much more attractive choice than when the job market was strong.

Accounting Profit versus Economic Profit

Let’s return to Maria from this chapter’s opening story. Assume, hypothetically, that Maria is offered a two-

First, let’s consider what Maria gains by getting the social work degree—

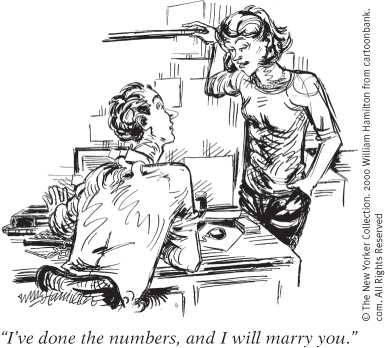

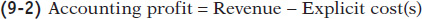

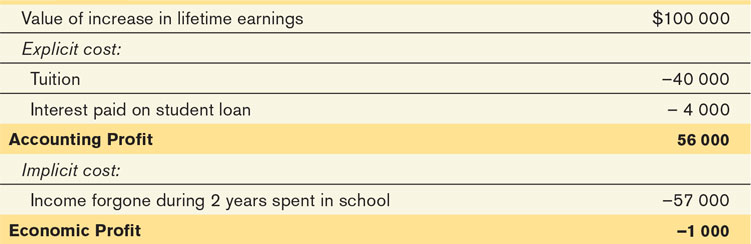

At this point, what she should do might seem obvious: if she chooses the social work degree, she gets a lifetime increase in the value of her earnings of $600 000 − $500 000 = $100 000, and she pays $40 000 in tuition plus $4000 in interest. Doesn’t that mean she makes a profit of $100 000 − $40 000 − $4000 = $56 000 by getting her social work degree? This $56 000 is Maria’s accounting profit from obtaining her social work degree: her revenue minus her explicit cost. In this example her explicit cost of getting the degree is $44 000, the amount of her tuition plus student loan interest:

Accounting profit is equal to revenue minus explicit cost.

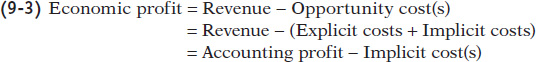

Although accounting profit is a useful measure, it would be misleading for Maria to use it alone in making her decision. To make the right decision, the one that leads to the best possible economic outcome for her, she needs to calculate her economic profit—the revenue she receives from the social work degree minus her opportunity cost of staying in school (which is equal to her explicit cost plus her implicit cost). In general, the economic profit of a given project will be less than the accounting profit because there are almost always implicit costs in addition to explicit costs:

Economic profit is equal to revenue minus the opportunity cost of resources used. It is usually less than the accounting profit.

When economists use the term profit, they are referring to economic profit, not accounting profit. This will be our convention in the remainder of the book: when we use the term profit, we mean economic profit.

How does Maria’s economic profit of staying in school differ from her accounting profit? We’ve already encountered one source of the difference: her two years of forgone job earnings. This is an implicit cost of going to school full time for two years. We assume that Maria’s total forgone earnings for the two years is $57 000.

Once we factor in Maria’s implicit costs and calculate her economic profit, we see that she is better off not getting a social work degree. You can see this in Table 9-2: her economic profit from getting the social work degree is −$1000. In other words, she incurs an economic loss of $1000 if she gets the degree. Clearly, she is better off sticking to financial services and going to work now.

To make sure that the concepts of opportunity costs and economic profit are well understood, let’s consider a slightly different scenario. Let’s suppose that Maria does not have to take out $40 000 in student loans to pay her tuition. Instead, she can pay for it with an inheritance from her grandmother. As a result, she doesn’t have to pay $4000 in interest. In this case, her accounting profit is $60 000 rather than $56 000. Would the right decision now be for her to get the social work degree? Wouldn’t the economic profit of the degree now be $60 000 − $57 000 = $3000?

Capital is the total value of assets owned by an individual or firm—

The answer is no, because Maria is using her own capital to finance her education, and the use of that capital has an opportunity cost even when she owns it. Capital is the total value of the assets of an individual or a firm. An individual’s capital usually consists of cash in the bank, stocks, bonds, and the ownership value of real estate such as a house. In the case of a business, capital also includes its equipment, its tools, and its inventory of unsold goods and used parts. (Economists like to distinguish between financial assets, also known as financial capital, such as cash, stocks, and bonds, and physical assets, also known as physical capital, such as buildings, equipment, tools, and inventory.)

The point is that even if Maria owns the $40 000, using it to pay tuition incurs an opportunity cost—

The implicit cost of capital is the opportunity cost of the use of one’s own capital—

This $4000 in forgone interest earnings is what economists call the implicit cost of capital—the income the owner of the capital could have earned if the capital had been employed in its next best alternative use. The net effect is that it makes no difference whether Maria finances her tuition with a student loan or by using her own funds. This comparison reinforces how carefully you must keep track of opportunity costs when making a decision.

Making “Either–Or” Decisions

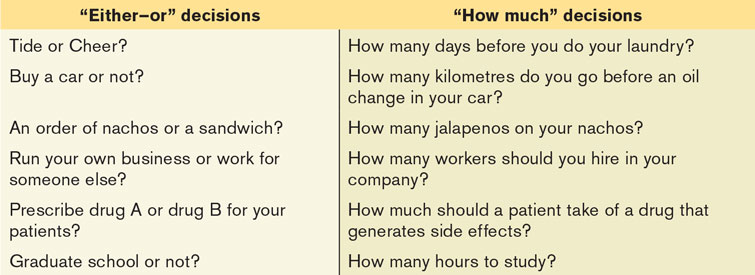

An “either–or” decision is one in which you must choose between two activities. Since doing one precludes you from doing the other, the choice is really between alternative A or alternative B. That’s in contrast to a “how much” decision, which requires you to choose how much of a given activity to undertake. For example, Maria faced an “either–or” decision: to spend two years obtaining a social work degree, or to work. In contrast, a “how much” decision would be deciding how many hours to study or how many hours to work at a job. Table 9-3 contrasts a variety of “either–or” and “how much” decisions.

In making economic decisions, as we have already emphasized, it is vitally important to calculate opportunity costs correctly. The best way to make an “either–or” decision, the method that leads to the best possible economic outcome, is the straightforward principle of “either–or” decision making. According to this principle, when making an “either–or” choice between two activities, choose the one with the positive economic profit. In other words, we should do an activity only if its benefit outweighs its opportunity cost.

According to the principle of “either–or” decision making, when faced with an “either–or” choice between two activities, choose the one with the positive economic profit.

WHY ARE THERE ONLY TWO CHOICES?

In “either–or” decision making, we have assumed that there are only two activities to choose from. But, what if, instead of just two alternatives, there are three or more? Does the principle of “either–or” decision making still apply?

Yes, it does. That’s because any choice between three (or more) alternatives can always be boiled down to a series of choices between two alternatives. Here’s an illustration using three alternative activities: A, B, or C. (Remember that this is an “either–or” decision: you can choose only one of the three alternatives.) Let’s say you begin by considering A versus B: in this comparison, A has a positive economic profit but B yields an economic loss. At this point, you should discard B as a viable choice because A will always be superior to B. The next step is to compare A to C: in this comparison, C has a positive economic profit but A yields an economic loss. You can now discard A because C will always be superior to A. You are now done: since A is better than B, and C is better than A, C is the correct choice.

But what is the opportunity cost of C? It looks like there are two possible answers: the opportunity cost of C compared to A and the opportunity cost of C compared to B. In general though, most economists like to quote only one opportunity cost. How do they do that? They quote the opportunity cost relative to the next best alternative. In our example, since A is better than B, this implies that “the opportunity cost of C” is the opportunity cost of C compared to A.

So if we are choosing among ten different options, the opportunity cost of the optimal option is a single answer rather than nine different opportunity costs. Of the nine inferior options, we ignore the eight least viable options. The economic profit of the optimal choice is equal to the revenue this choice brings minus the opportunity cost(s) of the next best option.

Let’s examine Maria’s dilemma from a different angle to understand how this principle works. First, recall Equation 9-3: the economic profit of an alternative is the revenue that choice brings minus the opportunity cost(s) of its alternative (the opportunity costs consist of both explicit and implicit costs). If Maria continues with financial services and goes to work immediately, the total value of her lifetime earnings (her revenue) is $57 000 (her earnings over the next two years) + $500 000 (the value of her lifetime earnings thereafter) = $557 000. Going to work immediately involves no explicit costs, but she does incur implicit costs. Let’s consider those implicit costs.

If she gets her social work degree instead and works in that field, the total value of her lifetime earnings (net of explicit costs) is $600 000 (value of her lifetime earnings after two years in school) − $40 000 (tuition) − $4000 (interest payments) = $556 000. So by going to work immediately, rather than school, her implicit cost is the forgone $556 000. Therefore the economic profit from continuing in financial services versus becoming a social worker is $557 000 − $556 000 = $1000.

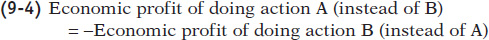

So the right choice for Maria is to begin work in financial services immediately, since this gives her an economic profit of $1000, rather than become a social worker, which would give her an economic profit of −$1000.1 In other words, by becoming a social worker she loses the $1000 economic profit she would have gained by working in financial services immediately.

When choosing between a pair of alternatives, notice that the economic profit of one alternative is always the opposite of the economic profit of the other. This is a general principle, so having calculated the economic profit of one alternative we immediately know the economic profit of the other alternative by using symmetry:

In making “either–or” decisions, mistakes most commonly arise when people or businesses use their own assets in projects rather than rent or borrow assets. That’s because they fail to account for the implicit cost of using self-owned capital. In contrast, when they rent or borrow assets, these rental or borrowing costs show up as explicit costs. If, for example, a restaurant owns its equipment and tools, it would have to compute its implicit cost of capital by calculating how much the equipment could be sold for and how much could be earned by using those funds in the next best alternative project. In addition, businesses run by the owner (an entrepreneur) often fail to calculate the opportunity cost of the owner’s time in running the business. In that way, small businesses often underestimate their opportunity costs and overestimate their economic profit of staying in business.

Are we implying that the hundreds of thousands who have chosen to go back to school rather than find work in recent years are misguided? Not necessarily. As we mentioned before, the poor job market had greatly diminished the opportunity cost of forgone wages for many students, making continuing their education the optimal choice for them.

The following Economics in Action illustrates just how important it is in real life to understand the difference between accounting profit and economic profit.

FARMING IN THE SHADOW OF SUBURBIA

Beyond the sprawling suburbs of the Golden Horseshoe region, much of southern Ontario is covered by a mix of farms and forests. This region is home to more than a quarter of Canada’s population. According to Statistics Canada, about half of Canada’s urbanized land is located on the country’s most productive farmland.

Many Ontario farms are located close to large metropolitan areas. These farmers can get high prices for their produce from city dwellers willing to pay a premium for locally grown, extremely fresh fruits and vegetables.

But now even these farms are under economic pressure caused by a rise in the implicit cost of farming close to a metropolitan area. As metropolitan areas have expanded during the last two decades, farmers increasingly ask themselves whether they could do better by selling their land to property developers.

In 2012, the average value of a hectare of farmland and buildings in Canada as a whole was $4443; in Ontario, home to half of Canada’s highest quality farmland, the average was $16 045. Since 2006, farmland prices in Canada have risen by 9% per year and triple the return of the Toronto Stock Exchange index over the past decade. The U.S. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston has noted that “high land prices put intense pressure on the region’s farms to generate incomes that are substantial enough to justify keeping the land in agriculture.”

The important point is that the pressure is intense even if the farmer owns the land because the land is a form of capital used to run the business. As Ron Bonnett, president of the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, has noted, development eats up land surrounding farms, driving land values up and with them property taxes. “This has an effect on the decision-making of any farmer who has to factor in the cost of purchasing additional land and debt servicing related to land ownership, and the increased rental costs as well.” So maintaining the land as a farm instead of selling it to a developer constitutes a large implicit cost of capital. A fact that two of the authors saw firsthand in 2009, when the 83-hectare Beckett Farm located just outside of Toronto was sold to developers for $100 million.

Less than 10% of Canada’s land can be farmed, only 0.5% of Canada’s land is class 1 (meaning it has no significant limitations for farming), and less than 1% of this class 1 land is suitable for growing tender fruit. The David Suzuki Foundation notes that “southern Ontario has some of the best remaining agricultural lands in Canada in terms of soil fertility, crop productivity, and economic value. While there is currently no effort to inventory or track the loss of agricultural land in Ontario, the most recent analysis found that between 1996 and 2001, 16% of the farmland in the Greater Toronto Area was lost to urban encroachment.” In the past four decades, urbanization in Canada has consumed an area of farmland about three times the size of Prince Edward Island. In the next 30 years Ontario’s population is expected to grow by another 2 million people, which could consume more than 40 000 acres of prime farmland.

Quick Review

All costs are opportunity costs. They can be divided into explicit costs and implicit costs.

An activity’s accounting profit is not necessarily equal to its economic profit.

Due to the implicit cost of capital—the opportunity cost of using self-owned capital—and the opportunity cost of one’s own time (labour), economic profit is often substantially less than accounting profit.

The principle of “either–or” decision making says that when making an “either–or” choice between two activities, choose the one with the positive economic profit.

Check Your Understanding 9-1

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9-1

Question 9.1

Karma and Don run a furniture-refinishing business from their home. Which of the following represent an explicit cost of the business and which represent an implicit cost?

Supplies such as paint stripper, varnish, polish, sandpaper, and so on

Basement space that has been converted into a workroom

Wages paid to a part-time helper

A van that they inherited and use only for transporting furniture

The job at a larger furniture restorer that Karma gave up in order to run the business

Supplies are an explicit cost because they require an outlay of money.

If the basement could be used in some other way that generates money, such as renting it to a student, then the implicit cost is that money forgone. Otherwise, the implicit cost is zero.

Wages are an explicit cost.

By using the van for their business, Karma and Don forgo the money they could have gained by selling it. So use of the van is an implicit cost.

Karma’s forgone wages from her job are an implicit cost.

Question 9.2

Assume that Maria has a third alternative to consider: entering a two-year apprenticeship program for skilled machinists that would, upon completion, make her a licensed machinist. During the apprenticeship, she earns a reduced salary of $15 000 per year. At the end of the apprenticeship, the value of her lifetime earnings is $725 000. What is Maria’s best career choice?

We need only compare the choice of becoming a machinist to the choice of taking a job in financial services in order to make the right choice. We can discard the choice of acquiring a social work degree because we already know that taking a job in financial services is always superior to it. Now let’s compare the remaining two alternatives: becoming a skilled machinist versus immediately taking a job in financial services. As an apprentice machinist, Maria will earn only $30 000 over the first two years, versus $57 000 in financial services. So she has an implicit cost of $30 000 − $57 000 = −$27 000 by becoming a machinist instead of immediately working in financial services. However, two years from now the value of her lifetime earnings as a machinist is $725 000 versus $500 000 in financial services, giving her an accounting profit of $225 000 by choosing to be a machinist. Summing, her economic profit from choosing a career as a machinist over a career in financial services is $225 000 − $27 000 = $198 000. In contrast, her economic profit from choosing the alternative, a career in financial services over a career as a machinist, is −$225 000 + $27 000 = −$198 000. By the principle of “either–or” decision making, Maria should choose to be a machinist because that career has a positive economic profit.

Question 9.3

Suppose you have three alternatives—A, B, and C—and you can undertake only one of them. In comparing A versus B, you find that B has an economic profit and A yields an economic loss. But in comparing A versus C, you find that C has an economic profit and A yields an economic loss. How do you decide what to do?

You can discard alternative A because both B and C are superior to it. But you must now compare B versus C. You should then choose the alternative—B or C—that carries a positive economic profit.