9.4 Behavioural Economics

Most economic models assume that people make choices based on achieving the best possible economic outcome for themselves. Human behaviour, however, is often not so simple. Rather than acting like economic computing machines, people often make choices that fall short—

It’s well documented that people consistently engage in irrational behaviour, choosing an option that leaves them worse off than other available options. Yet, as we’ll soon learn, sometimes it’s entirely rational for people to make a choice that is different from the one that generates the highest possible profit for themselves. For example, Maria may decide to earn a social work degree because she enjoys social work more than financial services, even though the profit from the social work degree is less than that from continuing with financial services.

The study of irrational economic behaviour was largely pioneered by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Kahneman won the 2002 Nobel Prize in economics for his work integrating insights from the psychology of human judgment and decision making into economics. Their work and the insights of others into why people often behave irrationally are having a significant influence on how economists analyze financial markets, labour markets, and other economic concerns.

Rational, but Human, Too

A rational decision maker chooses the available option that leads to the outcome he or she most prefers.

If you are rational, you will choose the available option that leads to the outcome you most prefer. But is the outcome you most prefer always the same as the one that gives you the best possible economic payoff? No. It can be entirely rational to choose an option that gives you a worse economic payoff because you care about something other than the size of the economic payoff. There are three principal rational reasons why people might prefer a worse economic payoff: concerns about fairness, bounded rationality, and risk aversion.

Concerns About Fairness In social situations, people often care about fairness as well as about the economic payoff to themselves. For example, no law requires you to tip a waiter or waitress. But concern for fairness leads most people to leave a tip (unless they’ve had outrageously bad service) because a tip is seen as fair compensation for good service according to society’s norms. Tippers are reducing their own economic payoff in order to be fair to waiters and waitresses. A related behaviour is gift-

A decision maker operating with bounded rationality makes a choice that is close to but not exactly the one that leads to the best possible economic outcome.

Bounded Rationality Being an economic computing machine—

Retailers are particularly good at exploiting their customers’ tendency to engage in bounded rationality. For example, pricing items in units ending in 99¢ takes advantage of shoppers’ tendency to interpret an item that costs, say, $2.99 as significantly cheaper than one that costs $3.00. Bounded rationality leads them to give more weight to the $2 part of the price (the first number they see) than the 99¢ part.

Risk aversion is the willingness to sacrifice some economic payoff in order to avoid a potential loss.

Risk Aversion Because life is uncertain and the future unknown, sometimes a choice comes with significant risk. Although you may receive a high payoff if things turn out well, the possibility also exists that things may turn out badly and leave you worse off. So even if you think a choice will give you the best payoff of all your available options, you may forgo it because you find the possibility that things could turn out badly too, well, risky. This is called risk aversion—the willingness to sacrifice some potential economic payoff in order to avoid a potential loss. (We’ll discuss risk aversion in more detail in Chapter 20.) Because risk makes most people uncomfortable, it’s rational for them to give up some potential economic gain in order to avoid it. In fact, if it weren’t for risk aversion, there would be no such thing as insurance.

Irrationality: An Economist’s View

An irrational decision maker chooses an option that leaves him or her worse off than choosing another available option.

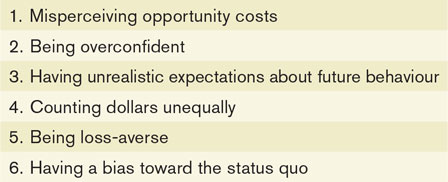

Sometimes, though, instead of being rational, people are irrational—they make choices that leave them worse off in terms of economic payoff and other considerations like fairness than if they had chosen another available option. Is there anything systematic that economists and psychologists can say about economically irrational behaviour? Yes, because most people are irrational in predictable ways. People’s irrational behaviour typically stems from six mistakes they make when thinking about economic decisions. The mistakes are listed in Table 9-7, and we will discuss each in turn.

Misperceptions of Opportunity Costs As we discussed at the beginning of this chapter, people tend to ignore nonmonetary opportunity costs—

For example, shortly after a firm spends thousands of dollars in upgrading their equipment, newer more efficient equipment becomes available. This newer equipment would allow the firm to produce its products at lower cost (and with higher expected future profit). However, it will cost the firm thousands of dollar to acquire the equipment. Focusing on the short-

Overconfidence It’s a function of ego: we tend to think we know more than we actually do. And even if alerted to how widespread overconfidence is, people tend to think that it’s someone else’s problem, not theirs. (Certainly not yours or mine!) For example, a 1994 study asked students to estimate how long it would take them to complete their thesis “if everything went as well as it possibly could” and “if everything went as poorly as it possibly could.” The results: the typical student thought it would take him or her 33.9 days to finish, with an average estimate of 27.4 days if everything went well and 48.6 days if everything went poorly. In fact, the average time it took to complete a thesis was much longer, 55.5 days. Students were, on average, from 14% to 102% more confident than they should have been about the time it would take to complete their thesis.

As you can see in the nearby For Inquiring Minds, overconfidence can cause problems with meeting deadlines. But it can cause far more trouble by having a strong adverse effect on people’s financial health. Overconfidence often persuades people that they are in better financial shape than they actually are. It can also lead to bad investment and spending decisions. For example, non-

Unrealistic Expectations About Future Behaviour Another form of overconfidence is being overly optimistic about your future behaviour: tomorrow you’ll study, tomorrow you’ll give up ice cream, tomorrow you’ll spend less and save more, and so on. Of course, as we all know, when tomorrow arrives, it’s still just as hard to study or give up something that you like as it is right now.

IN PRAISE OF HARD DEADLINES

Dan Ariely, a professor of psychology and behavioural economics, likes to do experiments with his students that help him explore the nature of irrationality. In his book Predictably Irrational, Ariely describes an experiment that gets to the heart of procrastination and ways to address it.

At the time, Ariely was teaching the same subject matter to three different classes, but he gave each class different assignment schedules. The grade in all three classes was based on three equally weighted papers.

Students in the first class were required to choose their own personal deadlines for submitting each paper. Once set, the deadlines could not be changed. Late papers would be penalized at the rate of 1% of the grade for each day late. Papers could be turned in early without penalty but also without any advantage, since Ariely would not grade papers until the end of the semester.

Students in the second class could turn in the three papers whenever they wanted, with no preset deadlines, as long as it was before the end of the term. Again, there would be no benefit for early submission.

Students in the third class faced what Ariely called the “dictatorial treatment.” He established three hard deadlines at the fourth, eighth, and twelfth weeks.

So which classes do you think achieved the best and the worst grades? As it turned out, the class with the least flexible deadlines—

Ariely learned two simple things about overconfidence from these results. First—

But the biggest revelation came from the class that set its own deadlines. The majority of those students spaced their deadlines far apart and got grades as good as those of the students under the dictatorial treatment. Some, however, did not space their deadlines far enough apart, and a few did not space them out at all. These last two groups did less well, putting the average of the entire class below the average of the class with the least flexibility. As Ariely notes, without well-

This experiment provides two important insights:

People who acknowledge their tendency to procrastinate are more likely to use tools for committing to a path of action.

Providing those tools allows people to make themselves better off.

If you have a problem with procrastination, hard deadlines, as irksome as they may be, are truly for your own good.

Strategies that keep a person on the straight-

Mental accounting is the habit of mentally assigning dollars to different accounts so that some dollars are worth more than others.

Counting Dollars Unequally If you tend to spend more when you pay with a credit card than when you pay with cash, particularly if you tend to splurge, then you are very likely engaging in mental accounting. This is the habit of mentally assigning dollars to different accounts, making some dollars worth more than others. By spending more with a credit card, you are in effect treating dollars in your wallet as more valuable than dollars on your credit card balance, although in reality they count equally in your budget.

Credit card overuse is the most recognizable form of mental accounting. However, there are other forms as well, such as splurging after receiving a windfall, like an unexpected inheritance, or overspending at sales, buying something that seemed like a great bargain at the time whose purchase you later regretted. It’s the failure to understand that, regardless of the form it comes in, a dollar is a dollar.

Loss aversion is an oversensitivity to loss, leading to unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on.

Loss Aversion Loss aversion is an oversensitivity to loss, leading to an unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on. In fact, in the lingo of the financial markets, “selling discipline”—being able and willing to quickly acknowledge when a stock you’ve bought is a loser and sell it—

Loss aversion can help explain why sunk costs are so hard to ignore: ignoring a sunk cost means recognizing that the money you spent is unrecoverable and therefore lost.

The status quo bias is the tendency to avoid making a decision and sticking with the status quo.

Status Quo Bias Another irrational behaviour is status quo bias, the tendency to avoid making a decision altogether. A well-

If everyone behaved rationally, then the proportion of employees enrolled in the company pension plan at opt-

Why do people exhibit status quo bias? Some claim it’s a form of “decision paralysis”: when given many options, people find it harder to make a decision. Others claim it’s due to loss aversion and the fear of regret, to thinking that “if I do nothing, then I won’t have to regret my choice.” Irrational, yes. But not altogether surprising. However, rational people know that, in the end, the act of not making a choice is still a choice.

Rational Models for Irrational People?

So why do economists still use models based on rational behaviour when people are at times manifestly irrational? For one thing, models based on rational behaviour still provide robust predictions about how people behave in most markets. For example, the great majority of farmers will use less fertilizer when it becomes more expensive—a result consistent with rational behaviour.

Another explanation is that sometimes market forces can compel people to behave more rationally over time. For example, if you are a small-business owner who persistently exaggerates your abilities or refuses to acknowledge that your favourite line of items is a loser, then sooner or later you will be out of business unless you learn to correct your mistakes. As a result, it is reasonable to assume that when people are disciplined for their mistakes, as happens in most markets, rationality will win out over time.

Finally, economists depend on the assumption of rationality for the simple but fundamental reason that it makes modelling so much simpler. Remember that models are built on generalizations, and it’s much harder to extrapolate from messy, irrational behaviour. Even behavioural economists, in their research, search for predictably irrational behaviour in an attempt to build better models of how people behave. Clearly, there is an ongoing dialogue between behavioural economists and the rest of the economics profession, and economics itself has been irrevocably changed by it.

“THE JINGLE MAIL BLUES”

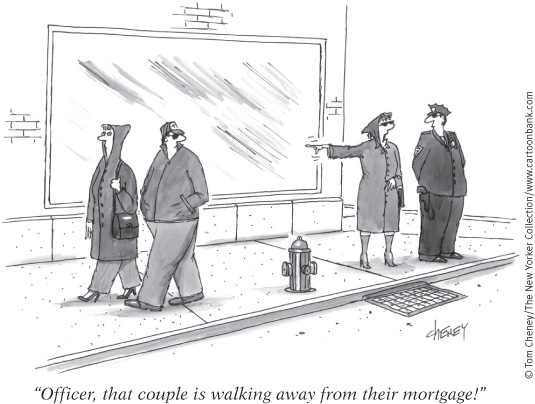

It’s called jingle mail—when a U.S. homeowner seals the keys to his or her house in an envelope and leaves them with the bank that holds the mortgage on the house. (A mortgage is a loan taken out to buy a house.) By leaving the keys with the bank, the homeowner is walking away not only from the house but also from the obligation to continue paying the mortgage. And to their great consternation, U.S. banks have been flooded with jingle mail in the last decade.

To default on a mortgage—that is, to walk away from one’s obligation to repay the loan and lose the house to the bank in the process—used to be a fairly rare phenomenon in the United States. For decades, continually rising U.S. home values made homeownership a good investment for the typical U.S. household. In recent years, though, an entirely different phenomenon—called “strategic default”—has appeared. In a strategic default, a homeowner who is financially capable of paying the mortgage instead chooses not to, voluntarily walking away. Strategic defaults account for a significant proportion of U.S. jingle mail; in March 2010, they accounted for 31% of all foreclosures, up from 22% in 2009. And unfortunately that number will likely be slow to change. In the spring of 2011, strategic defaults still accounted for 30% of all defaults. By 2013, rising home prices had lifted an additional 2.5 million homes into positive equity territory in the second quarter, and foreclosures in August were down 34% year over year. Although this news was positive, home price gains were slowing, household incomes were declining, and interest rates were expected to climb. According to CoreLogic, as of August 2013, about 7.1 million homes in the United States (14.5% of all homes with a mortgage), were in negative equity; these homeowners owed more than their homes were worth, making them prime candidates for strategic default. A further 10.3 million homes (21.2% of all homes with a mortgage), are “under-equitied,” meaning they have less than 20% equity. This later group is essentially locked into their homes as selling and moving would cost so much that they would come out behind.

What happened? The Great American Housing Bust happened. After decades of huge increases, house prices began a precipitous fall in 2008. Prices dropped so much that a significant proportion of homeowners found their homes “underwater”—they owed more on their homes than the homes were worth. And with house prices projected to stay depressed for several years, possibly a decade, there appeared to be little chance that an underwater house would recover its value enough in the foreseeable future to move “abovewater.”

Many homeowners suffered a major loss. They lost their down payment, money spent on repairs and renovation, moving expenses, and so on. And because they were paying a mortgage that was greater than the house was now worth, they found they could rent a comparable dwelling for less than their monthly mortgage payments. In the words of Benjamin Koellmann, who paid $215 000 for an apartment in Miami where similar units were now selling for $90 000, “There is no financial sense in staying.”

Realizing their losses were sunk costs, underwater homeowners walked away. Perhaps they hadn’t made the best economic decision when purchasing their houses, but in leaving them showed impeccable economic logic.

Quick Review

Behavioural economics combines economic modelling with insights from human psychology.

Rational behaviour leads to the outcome a person most prefers. Bounded rationality, risk aversion, and concerns about fairness are reasons why people might prefer outcomes with worse economic payoffs.

Irrational behaviour occurs because of misperceptions of opportunity costs, overconfidence, mental accounting, and unrealistic expectations about the future. Loss aversion and status quo bias can also lead to choices that leave people worse off than they would be if they chose another available option.

Check Your Understanding 9-4

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 9-4

Question 9.8

Which of the types of irrational behaviour are suggested by the following events?

Although the housing market has fallen and Jenny wants to move, she refuses to sell her house for any amount less than what she paid for it.

Dan worked more overtime hours last week than he had expected. Although he is strapped for cash, he spends his unexpected overtime earnings on a weekend getaway rather than trying to pay down his student loan.

Carol has just started her first job and deliberately decided to opt out of the company’s savings plan. Her reasoning is that she is very young and there is plenty of time in the future to start saving. Why not enjoy life now?

Jeremy’s company requires employees to download and fill out a form if they want to participate in the company-sponsored savings plan. One year after starting the job, Jeremy had still not submitted the form needed to participate in the plan.

Jenny is exhibiting loss aversion. She has an oversensitivity to loss, leading to an unwillingness to recognize a loss and move on.

Dan is doing mental accounting. Dollars from his unexpected overtime earnings are worth less—spent on a weekend getaway—than the dollars earned from his regular hours that he uses to pay down his student loan.

Carol may have unrealistic expectations of future behaviour. Even if she does not want to participate in the plan now, she should find a way to commit to participating at a later date.

Jeremy is showing signs of status quo bias. He is avoiding making a decision altogether; in other words, he is sticking with the status quo.

Question 9.9

How would you determine whether a decision you made was rational or irrational?

You would determine whether a decision was rational or irrational by first accurately accounting for all the costs and benefits of the decision. In particular, you must accurately measure all opportunity costs. Then calculate the economic payoff of the decision relative to the next best alternative. If you would still make the same choice after this comparison, then you have made a rational choice. If not, then the choice was irrational.

Question 9.10

Suppose you are approached by a corporation that asks you to go over Niagara Falls in their newly designed Barrel-o-Death. Your chance of survival is one in a million, but the corporation has guaranteed to pay you $10 million if you survive. If you are not successful you will be paid nothing and the corporation is not liable for your death. Are you rational, irrational, risk averse, or a risk lover if you decline the offer?

You are being rational in declining the offer because the expected benefits—receiving $10 million with only a 1-in-a-million chance of survival—is less than the expected costs—losing your life.

Banks Help Cardholders Be CreditSmart and inControl

In 2007, CIBC, Canada’s fifth largest bank with about 11 million customers, served by 1100 bank branches throughout Canada, and a market capitalization of more than $35 billion, became the first Canadian company to introduce a free and unique suite of information and credit management tools, which they named CreditSmart. Available to all CIBC credit card holders, this suite contains enhanced monthly statements, plus budgeting and alert features that help cardholders stay within their spending limits and prevent credit card fraud. With CreditSmart, cardholders can do the following:

Use enhanced statements to better track and manage spending in 10 common categories

Set up budgets for particular types of spending

Set up and manage a budget spending limit on each spending category—including personalized custom categories

Monitor changes to their Equifax credit reports, be aware of fraudulent uses of their cards, and deal with identity theft

Receive alerts via phone, email, or through CIBC’s Online Banking Message Centre to safeguard against overspending (related to personal budget or credit limit) and fraud

According to CIBC, “Canadians planning to use a credit card to pay for their holiday (or other) expenses should ensure they have a plan to pay off their balance to avoid incurring interest charges. With a plan in place, you can earn rewards for your purchases that may save you money on other items, such as discounts on gas purchases or cash back.” And CreditSmart gives them the tools to do so. Cheryl Longo from CIBC explained that “you can set your budget and we will send you alerts, so you can be your own money manager, your own smart money manager. If you say, ‘I don’t want to spend more than x amount,’ we will send you an alert when you hit that amount. But consumers have a choice, and they need to take accountability for the choices they make.”

Following suit, the Bank of Montreal, Canada’s fourth largest bank, introduced a special set of features known as inControl to their MasterCard. Previously introduced in the United Kingdom by Barclays Bank, inControl cards, like the CreditSmart suite, contain budgeting and alert features that help credit card holders stay within their spending limits and prevent credit card fraud. inControl contains one major feature not found in the CreditSmart suite: the ability of cardholders to manage where, when, how, and for what types of purchases their credit cards can be used.2

Users of inControl can customize their cards, choosing to either receive alerts or have a card declined when they are exceeding their limits. So, for example, if you choose the latter and have set a monthly limit on restaurant meals, your card will be rejected for restaurant bills above your preset cap. Cardholders can also arrange to have their credit cards shut off once a limit that corresponds to monthly disposable income is reached.

Until inControl was introduced, no other product allowed you to completely cut off certain types of spending. “The personalization of consumer products has reached far deeper than it ever has before,” says Ed McLaughlin, chief payments officer of MasterCard.

But what about the obvious question of whether credit card companies are hurting or helping themselves by introducing this product? After all, if consumers get serious about budgeting and place caps on their credit card spending, won’t that reduce the interest that credit card companies profit from? In answer to this question, McLaughlin replied, “I think anyone knows that having a superior offering wins out in the long run.”

The service, though, is not ironclad—having hit the self-imposed limit, a customer can turn the card back on with a phone call or text message. The thinking goes, however, that having your card rejected will make a significant enough impression to put a damper on your urge to splurge.

In the end, how well inControl does, and whether something like it is adopted by competitors like VISA, depends on whether customers actually use the service and how much customers’ newfound discipline hurts credit card companies’ bottom lines.

QUESTIONS FOR THOUGHT

Question 9.11

What aspects of decision making does the CreditSmart suite and inControl card address? Be specific.

Question 9.12

Consider credit scores, the scores assigned to individuals by credit-rating agencies, based on whether you pay your bills on time, how many credit cards you have (too many is a bad sign), whether you have ever declared bankruptcy, and so on. Now consider people who choose inControl cards and those who don’t. Which group do you think has better credit scores before they adopt the inControl cards? After adopting the inControl cards? Explain.

Question 9.13

What do you think explains Ed McLaughlin’s optimism that his company will profit from the introduction of inControl?