Conducting Secondary Research

When you conduct secondary research, you are trying to learn what experts have to say about a topic. Whether that expert is a world-

Sometimes you will do research in a library, particularly if you need specialized handbooks or access to online subscription services that are not freely available on the Internet. Sometimes you will do your research on the web. As a working professional, you might find much of the information you need in your organization’s information center. An information center is an organization’s library, a resource that collects different kinds of information critical to the organization’s operations. Many large organizations have specialists who can answer research questions or who can get articles or other kinds of data for you.

USING TRADITIONAL RESEARCH TOOLS

86

There is a tremendous amount of information in the different media. The trick is to learn how to find what you want. This section discusses six basic research tools.

Online Catalogs An online catalog is a database of books, microform materials, films, compact discs, phonograph records, tapes, and other materials. In most cases, an online catalog lists and describes the holdings at one particular library or a group of libraries. Your college library has an online catalog of its holdings. To search for an item, consult the instructions, which explain how to limit your search by characteristics such as types of media, date of publication, and language. The instructions also explain how to use punctuation and words such as and, or, and not to focus your search effectively.

Reference Works Reference works include general dictionaries and encyclopedias, biographical dictionaries, almanacs, atlases, and dozens of other research tools. These print and online works are especially useful when you are beginning a research project because they provide an overview of the subject and often list the major works in the field.

How do you know if there is a dictionary of the terms used in a given field? The following reference books—

Hacker, D., and Fister, B. (2015). Research and documentation in the digital age (6th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Kennedy, X. J., Kennedy, D. M., and Muth, M. F. (2014). The Bedford guide for college writers with reader, research manual, and handbook (10th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Lester, R. (Ed.). (2008). The new Walford guide to reference resources (Vol. 1: Science, Technology and Medicine; Vol. 2: Social Sciences). London: Neal-

To find information on the web, go to the “reference” section of a library website or search engine. There you will find links to excellent collections of reference works online, such as Infomine and ipl2.

Periodical Indexes Periodicals are excellent sources of information because they offer recent, authoritative discussions of specific subjects. The biggest challenge in using periodicals is identifying and locating the dozens of articles relevant to any particular subject that are published each month. Although only half a dozen major journals might concentrate on your field, a useful article could appear in one of hundreds of other publications. A periodical index, which is a list of articles classified according to title, subject, and author, can help you determine which journals you want to locate.

87

There are periodical indexes in all fields. The following brief list will give you a sense of the diversity of titles:

Applied Science & Technology Index

Business Source Premier

Engineering Village

Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature

You can also use a directory search engine. Many directory categories include a subcategory called “journals” or “periodicals” that lists online and printed sources.

Once you have created a bibliography of printed articles you want to study, you have to find them. Check your library’s online catalog, which includes all the journals your library receives. If your library does not have an article you want, you can use one of two techniques for securing it:

Interlibrary loan. Your library finds a library that has the article. That library scans the article and sends it to your library. This service can take more than a week.

Document-

delivery service. If you are in a hurry, you can log on to a document- delivery service, such as IngentaConnect, a free database of 5 million articles in 10 thousand periodicals. There are also fee- based document- delivery services.

Newspaper Indexes Many major newspapers around the world are indexed by subject. The three most important indexed U.S. newspapers are the following:

the New York Times, perhaps the most reputable U.S. newspaper for national and international news

the Christian Science Monitor, another highly regarded general newspaper

the Wall Street Journal, the most authoritative news source on business, finance, and the economy

Many newspapers available on the web can be searched electronically, although sometimes there is a charge for archived articles. Keep in mind that the print version and the electronic version of a newspaper can vary greatly. If you wish to quote from an article in a newspaper, the print version is the preferred one.

88

Abstract Services Abstract services are like indexes but also provide abstracts: brief technical summaries of the articles. In most cases, reading the abstract will enable you to decide whether to seek out the full article. The title of an article alone can often mislead you about its contents.

For more about abstracts, see “Writing Recommendation Reports” in Ch. 13.

Some abstract services, such as Chemical Abstracts Service, cover a broad field, but many are specialized rather than general. Fuente Académica, for instance, focuses on Basque studies. Figure 5.1 shows an abstract from AnthroSource, an abstract service covering anthropology journals.

Government Information The U.S. government is the world’s biggest publisher. In researching any field of science, engineering, or business, you are likely to find that a federal agency or department has produced a relevant brochure, report, or book.

Government publications are cataloged and shelved separately from other kinds of materials. They are classified according to the Superintendent of Documents system, not the Library of Congress system. A reference librarian or a government-

For more about RFPs, see “The Logistics of Proposals” in Ch. 11.

You can also access various government sites and databases on the Internet. For example, if your company wishes to respond to a request for proposals (RFP) published by a federal government agency, you will find that RFP on a government site. The major entry point for federal government sites is USA.gov (usa.gov), which links to hundreds of millions of pages of government information and services. It also features tutorials, a topical index, online transactions, and links to state and local government sites.

89

USING SOCIAL MEDIA AND OTHER INTERACTIVE RESOURCES

Watch a tutorial on using online tools to organize your research.

Social media and other interactive resources enable people to collaborate, share, link, and generate content in ways that traditional websites offering static content cannot. The result is an Internet that can harness the collective intelligence of people around the globe—

This discussion covers three categories of social media and web-

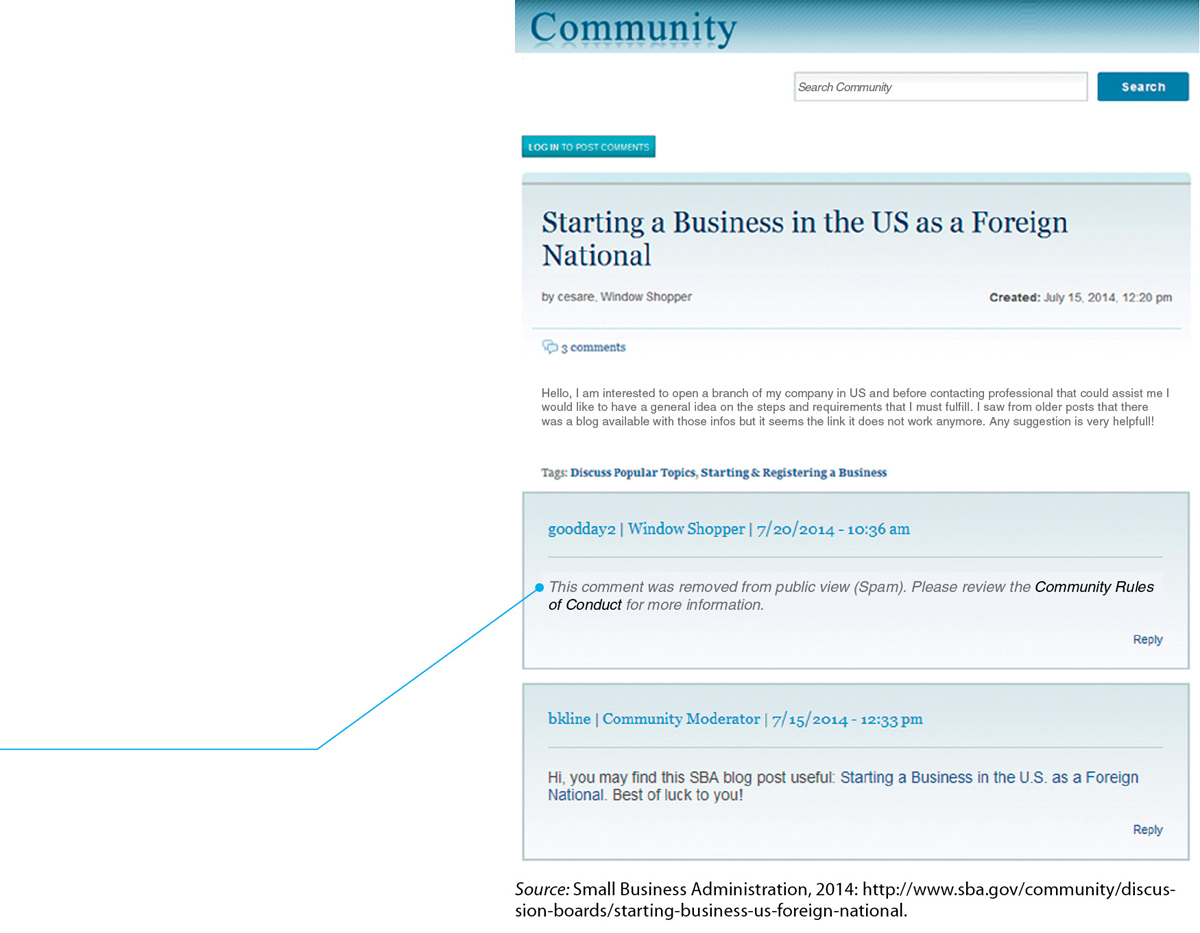

Discussion Boards Discussion boards, online discussion forums sponsored by professional organizations, private companies, and others, enable researchers to tap a community’s information. Discussion boards are especially useful for presenting quick, practical advice. However, the advice might or might not be authoritative. Figure 5.2 shows one interchange related to starting a business as a foreign national.

If you use a search engine to find this interchange, you are performing secondary research: discovering what has already been written or said about a topic. If you post a question to a discussion board (or comment on a blog post) and someone responds, you are performing primary research, just as if you were interviewing that person. For more on primary research, see “Conducting Primary Research.” But don’t worry too much about whether you are doing primary or secondary research; worry about whether the information is accurate and useful.

Moderators who oversee discussion boards routinely delete comments from trolls advertising weight-

Wikis A wiki is a website that makes it easy for members of a community, company, or organization to create and edit content collaboratively. Often, a wiki contains articles, information about student and professional conferences, reading lists, annotated sets of links, book reviews, and documents used by members of the community. You might have participated in creating and maintaining a wiki in one of your courses or as a member of a community group outside of your college.

Wikis are popular with researchers because they contain information that can change from day to day, on topics in fields such as medicine or business. In addition, because wikis rely on information contributed voluntarily by members of a community, they represent a much broader spectrum of viewpoints than media that publish only information that has been approved by editors. For this reason, however, you should be especially careful when you use wikis; the information they contain might not be trustworthy. It’s a good idea to corroborate any information you find on a wiki by consulting other sources.

An excellent example of how organizations use wikis is provided by the federal government’s Mobile Gov, a set of wikis whose purpose is to make “anytime, anywhere, any-

90

How do you search wikis? You can use any search engine and add the word “wiki” to the search. Or you can use a specialized search engine such as Wiki.com.

For more about blogs, see “Writing Microblogs” in Ch. 9.

Blogs Many technical and scientific organizations, universities, and private companies sponsor blogs that offer useful information for researchers.

Keep in mind that bloggers are not always independent voices. A Hewlett-

91

Figure 5.3, a screenshot of a portion of NASA’s My Big Fat Planet blog, offers information that is likely to be credible, accurate, and timely.

Tagged Content Tags are descriptive keywords people use to categorize and label content such as blog entries, videos, podcasts, and images they post to the Internet or bookmarks they post to social-

RSS Feeds Repeatedly checking for new content on many different websites can be a time-

EVALUATING THE INFORMATION

92

For more about taking notes, paraphrasing, and quoting, see Appendix, Part A.

You’ve taken notes, paraphrased, and quoted from your secondary research. Now, with more information than you can possibly use, you try to figure out what it all means. You realize that you still have some questions—

Accurate. Suppose you are researching whether your company should consider flextime scheduling. If you estimate the number of employees who would be interested in flextime to be 500 but it is in fact closer to 50, inaccurate information will cause you to waste time doing an unnecessary study.

Unbiased. You want sources that have no financial stake in your project. A private company that transports workers in vans is likely to be a biased source because it could profit from flextime, making extra trips to bring employees to work at different times.

Comprehensive. You want information from different kinds of people—

in terms of gender, cultural characteristics, and age— and from people representing all viewpoints on the topic. Appropriately technical. Good information is sufficiently detailed to meet the needs of your readers, but not so detailed that they cannot understand it or do not need it. For the flextime study, you need to find out whether opening your building an hour earlier and closing it an hour later would significantly affect your utility costs. You can get this information by interviewing people in the Operations Department; you do not need to do a detailed inspection of all the utility records of the company.

Current. If your information is 10 years old, it might not accurately reflect today’s situation.

Clear. You want information that is easy to understand. Otherwise, you’ll waste time figuring it out, and you might misinterpret it.

The most difficult kind of material to evaluate is user-

93

Evaluating Print and Online Sources

| FOR PRINTED SOURCES | FOR ONLINE SOURCES |

|

|

| Do you recognize the name of the author? Does the source describe the author’s credentials and current position? If not, can you find this information in a “who’s who” or by searching for other books or other journal articles by the author? | If you do not recognize the author’s name, is the site mentioned on another reputable site? Does the site contain links to other reputable sites? Does it contain biographical information— |

|

|

| What is the publisher’s reputation? A reliable book is published by a reputable trade, academic, or scholarly publisher; a reliable journal is sponsored by a professional association or university. Are the editorial board members well known? | Can you determine the publisher’s identity from headers or footers? Is the publisher reputable? |

| Trade publications— |

If the site comes from a personal account, the information it offers might be outside the author’s field of expertise. Many Internet sites exist largely for public relations or advertising. For instance, websites of corporations and other organizations are unlikely to contain self- |

|

|

| Does the author appear to be knowledgeable about the major literature on the topic? Is there a bibliography? Are there notes throughout the document? | Analyze the Internet source as you would any other source. Often, references to other sources will take the form of links. |

|

|

| Is the information based on reasonable assumptions? Does the author clearly describe the methods and theories used in producing the information, and are they appropriate to the subject? Has the author used sound reasoning? Has the author explained the limitations of the information? | Is the site well constructed? Is the information well written? Is it based on reasonable assumptions? Are the claims supported by appropriate evidence? Has the author used sound reasoning? Has the author explained the limitations of the information? Are sources cited? Online services such as BlogPulse help you evaluate how active a blog is, how the blog ranks compared to other blogs, and who is citing the blog. Active, influential blogs that are frequently linked to and cited by others are more likely to contain accurate, verifiable information. |

|

|

| Does the document rely on recent data? Was the document published recently? | Was the document created recently? Was it updated recently? If a site is not yet complete, be wary. |