CHAPTER 7: Communication Styles and Team Diversity

Chapter 7

Communication Styles and Team Diversity

When they were asked in their final interviews to comment on how individual team members got along, Veronica and David had this to say about each other:

Veronica: It was a headache because the things that I said weren’t being heard. If someone asked a question and I tried to answer it, David especially would interrupt me. . . . So I just started to sit back and not say anything because I got tired of, you know, having to shout to be heard. It felt like it didn’t matter what I said; they’re not going to listen.

David: Well, I think Veronica, she might have the worst view of me because she and I just come from different places. With her, I kind of felt like I had to watch what I said because there were some issues there. Do you understand what I’m saying? Whereas with other people, I didn’t have to make sure. If I ignored or interrupted them, it wasn’t this big issue.

Veronica and David have conflicting communication styles, among other issues. Whereas Veronica perceives interruptions as a sign of disrespect — an indication that others don’t care about what she has to say — David sees interruptions as part of the normal ebb and flow of a debate. He feels that he has to curb his normal style of talking in order to accommodate Veronica and wishes that she could be more like the others in his group. As David notes, he and Veronica “just come from different places.” He worries about how she perceives him, and vice versa.

Sooner or later, you will find yourself on a team with someone who “comes from a different place” than you do. This chapter teaches you to take the differences between you and your teammate and turn them into something positive. Key to achieving this positive outcome is understanding the differences in communication styles. Many interpersonal problems occur on teams because team members differ in their assumptions about how they should talk to one another, what constitutes productive behavior, and what constitutes rude behavior. Understanding that people can have different assumptions about what is “normal” communication will help you work with others whose communication preferences differ from yours.

The best teams are those that are easy on people but hard on problems. This chapter teaches you about communication styles so that the merit of an idea or a solution — and not how it was communicated — determines whether or not your team adopts it.

The Benefits of Diverse Teams

A diverse team is one composed of people of different genders, ethnicities, or educational backgrounds or from different geographic regions. Although diverse teams sometimes experience social discomfort as people learn to work together, researchers have found that diverse teams outperform homogeneous ones (teams composed of people with similar backgrounds) — particularly on complex tasks without clear solutions (Cordero et al., 1996). These findings should not be surprising if you think back to Chapter 5, “Constructive Conflict,” which showed that teams work best when they experience productive conflict by fully considering the merits and drawbacks of a range of ideas. Teams composed of people from diverse perspectives and backgrounds are likely to propose diverse solutions to problems. Such teams will have more opportunities for such constructive conflict than teams in which everybody thinks and acts alike. Thus, diversity often leads to creativity and innovative problem solving.

Moreover, diverse teams are far less likely than homogeneous ones to propose solutions that work only for a single group of people. For instance, when car air bags first became common in the 1980s, designers and auto manufacturers, who were mostly male, tested them on dummies measuring 5 feet 9 inches — the height of the average American man. Only after many women and children were injured and even killed by inappropriately deploying air bags did automakers realize that this safety device could actually harm people with smaller body frames. Today, air bags are now designed and tested for a range of body types, including pregnant women. If more women had been involved in auto-manufacturing design in the 1980s, this fatal design flaw probably would have been noted and addressed earlier.

However, even if diverse teams didn’t have advantages over homogeneous ones, there is at least one practical reason for learning how to work with people different from us: as our culture becomes more global, our workplaces will become increasingly diverse, and therefore homogeneous teams will become less and less common. Learning how to handle diversity successfully is becoming a necessary job skill. Understanding how norms work in interpersonal interactions is the first step in acquiring that skill.

How Differences in Communication Norms Can Cause Interpersonal Conflict

By understanding how norms affect your behavior and your perception of other people’s behaviors, you can foster a team environment that reaps the benefits of diversity while minimizing the dissatisfaction that diversity causes. In the realm of communication and other interpersonal issues, a norm is a standard of behavior typical of a particular group. An individual norm is what a particular member of that group considers to be normal behavior. Norms govern how we think, talk, and act. When team members have conflicting norms, they will have different ideas about what is productive or unproductive as well as conflicting ideas about what is polite, mildly offensive, or just plain rude.

An illustration of different communication norms can be seen in how people from different cultures respond to compliments. In the United States, children are usually taught that it is polite to accept compliments, usually by saying “thank you.” In Japan and Korea, however, children are taught to deflect or deny compliments by saying “no, no” or “that’s not true” (Kim, 2003). A Korean unfamiliar with American cultural norms might think that an American was egotistical for accepting a compliment; conversely, an American might think that a Korean was rude for refusing to accept one. Yet no one way of responding to compliments is inherently better than another — your preference is just a result of what you were brought up to see as normal.

Even within a single culture — especially one as diverse as U.S. culture — there are wide differences in what is considered normal behavior. For instance, some behavior that is considered normal in a crowded area such as New York City may be perceived as rude in other parts of the country. Similarly, what a southerner may view as a polite and necessary conversation-starter might be perceived as an infuriating waste of time by a midwesterner. Even within a particular geographic region, men and women, or people from different social classes, may have different norms. For example, behavior that might be considered normal and appropriate in single-gender settings is often considered inappropriate in mixed company. Similarly, one group of people may find it natural and normal to talk about their accomplishments, whereas another group in the same community may see such talk as egotistical and self-promotional.

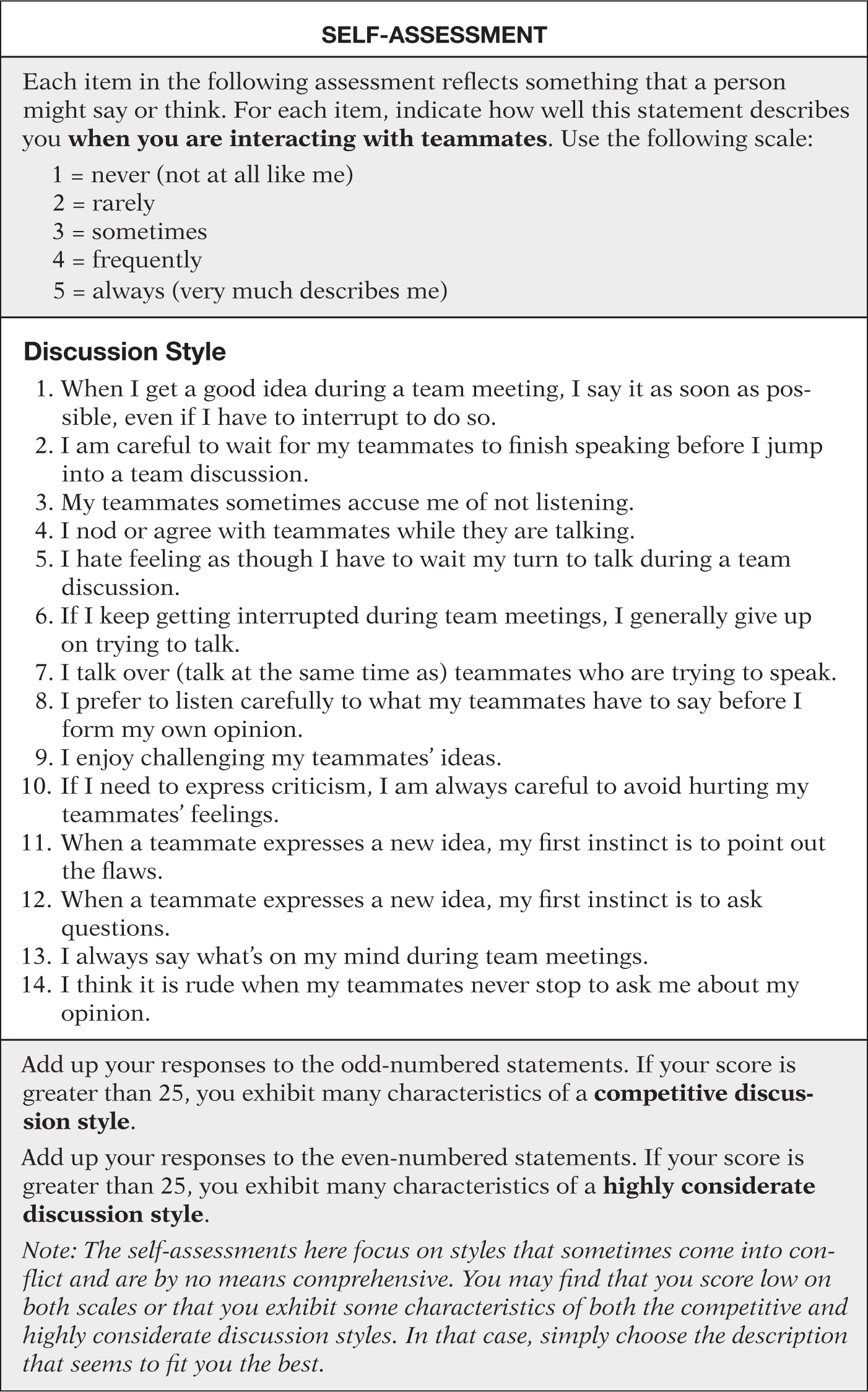

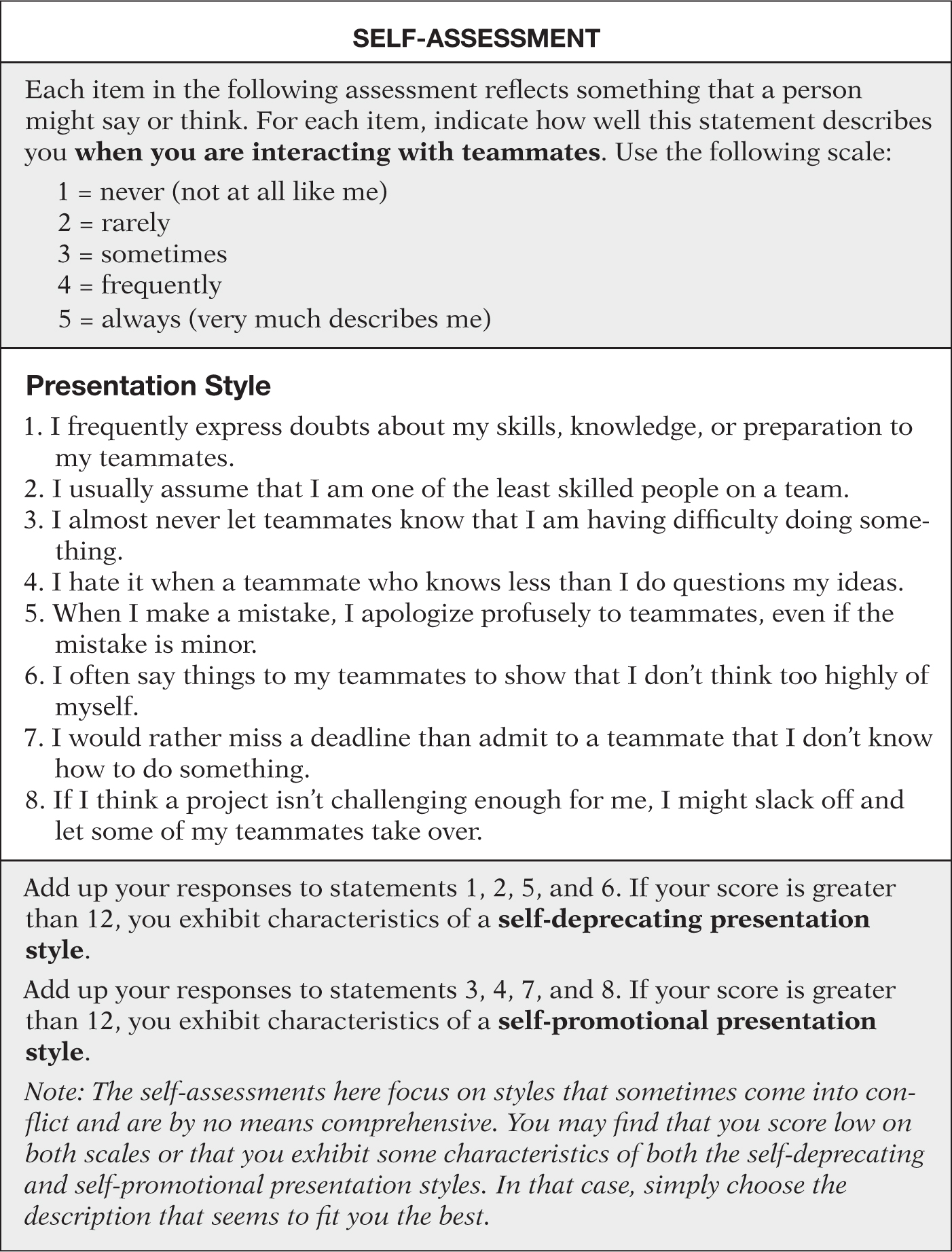

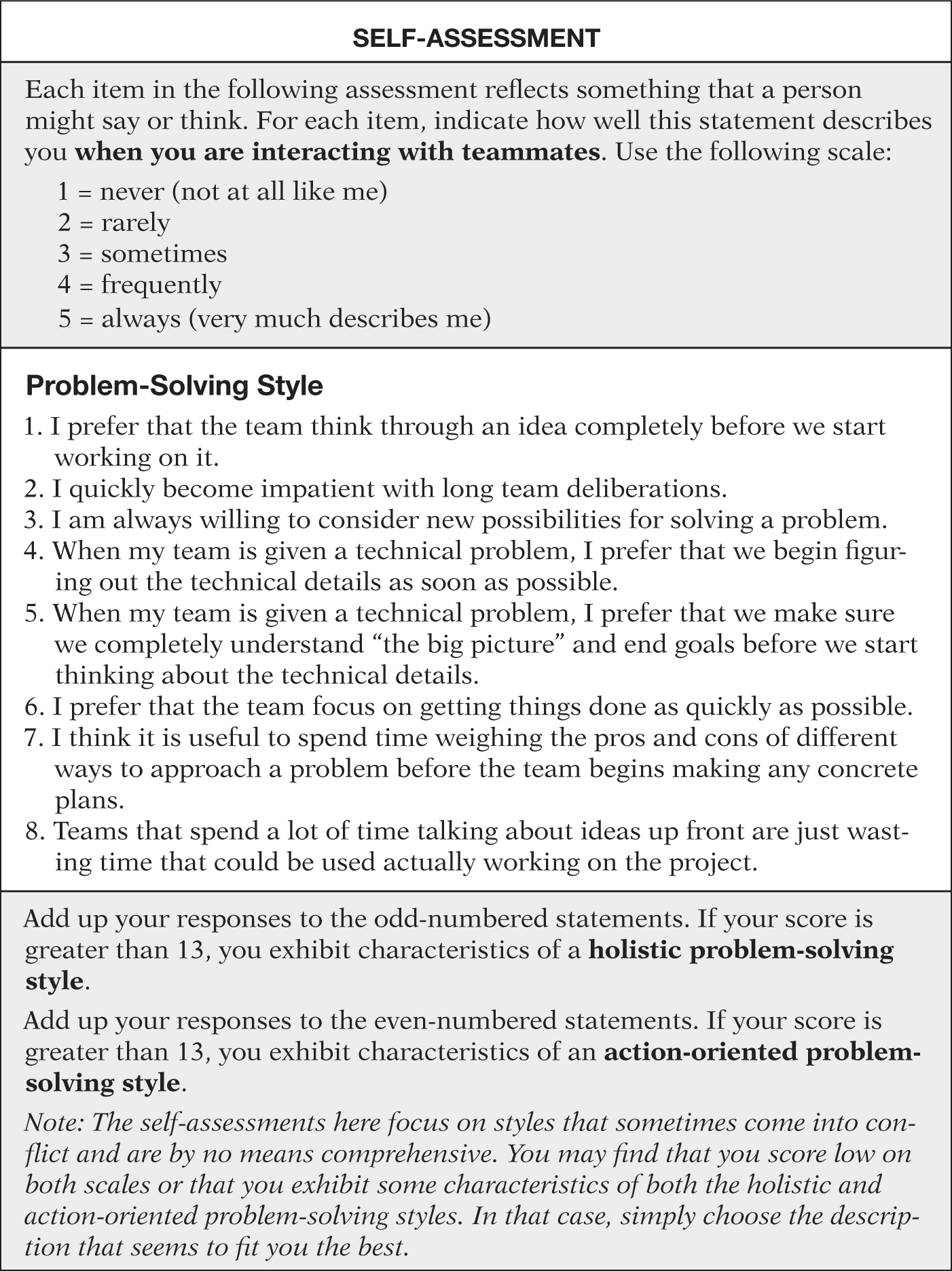

Increasing your awareness of social norms can help you reduce unproductive conflict, know how to adjust your behavior to “fit in” to otherwise unfamiliar or uncomfortable social situations, and understand why others might have difficulty fitting in to norms that feel natural to you. This chapter discusses three areas in which different norms often cause conflict in student teams. Before continuing, take the self-assessments in Figures 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 to see what sort of norms you favor in team interactions. (Download a copy of these self-assessments: Discussion Style, Presentation Style, Problem Solving Style.)

Understanding Norms

Taking these self-assessments will help you identify what feels like a “normal” discussion, self-presentation, or problem-solving style to you. These self-assessments and the discussion in the rest of the chapter offer three basic lessons:

- What feels “normal” to you may be different from what feels “normal” to others.

- People whose norms differ from yours are not necessarily egotistical, insecure, or rude — they may just have different ideas and assumptions about what is appropriate behavior.

- When working in a group setting, you may need to change your norms — in other words, change your normal patterns of talk or behavior — to do what is best for the group as a whole.

Note

You may find that none of the communication and interpersonal styles measured in the self-assessments characterize you — or that you have the characteristics of multiple norms. That’s perfectly fine, and far more norms exist than this text could possibly cover. The purpose of this chapter is to expose you to some of the norms your teammates may exhibit and to provide you with strategies for interacting with people whose norms you may not share.

Table 7.1 provides information about some common norms and their pros and cons. It provides only a small sampling of the norms that sometimes lead to unproductive conflict in teams. You may find that several of these norms describe you — or that none of them describe you. Or, because most of these norms represent extremes, you may find that you fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. The goal here is to recognize that people can have some strong differences in their assumptions about what is appropriate and effective communication and teamwork.

Table 7.1. Some communication norms and their pros and cons

| Area | Norm | Definition | Pros and Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discussion style | Competitive | Conversation is a miniature battle over ideas. Speakers tend to be passionate in supporting their ideas, and interruptions are frequent. | Those who hold this norm like the fast-paced conversation and the challenge of publicly defending ideas in the face of competition. However, those who don’t share this norm perceive it as rude and disrespectful. Moreover, this norm works against constructive conflict because speakers are more concerned with defending their own ideas than with carefully listening to their teammates. Often, the most aggressive speaker rather than the best idea wins out. |

| Highly considerate | Speakers acknowledge and support one another’s contributions, and disagreements are often indirect. Interruptions are rare, and the conversation often pauses to allow new people to speak. | Those who hold this norm like the polite tone, concern for others, and equitable conversations that it fosters. However, those who don’t share it find these conversations slow-moving and frustrating and sometimes think that highly considerate speakers have nothing important to say. Moreover, this norm sometimes privileges feelings and emotions over constructive criticism of ideas. | |

| Presentation style | Self-promotional | Speakers aggressively display their own confidence and expertise, often criticizing others to make themselves look better. | This norm sometimes benefits people who may expect special treatment for their expertise but is generally harmful to the group dynamics. Self-promotional speakers tend to see asking for help as a weakness and to see criticism as a direct attack on themselves. |

| Self-deprecating | Speakers display their modesty and talk about their own shortcomings. | Even though people (especially men) who engage in humorous self-deprecation may be perceived as likable and easy to get along with, this norm can make group members distrust the speaker’s ability to do competent work. Sometimes, self-deprecating speakers are perceived as trying to get out of work. | |

| Problem-solving style | Action-oriented | People immediately jump into the details of a problem and start working on a solution right away. | This style is very effective for getting things done quickly, but sometimes groups waste time by working on solutions before they fully understand the problem. |

| Holistic | People consider the entire problem as a whole and refrain from proposing solutions until the problem is completely understood. | This style generally helps groups propose better solutions because it ensures that they are solving the correct problem. However, the holistic problem-solving style requires more time. Moreover, action-oriented problem solvers sometimes find this style frustrating to work with. |

Being aware of the norms in Table 7.1 can help you avoid thinking negatively about others. For instance, you might realize that competitive speakers are not deliberately being rude but are acting in ways that feel normal to them. Or you might realize that a self-deprecating speaker is not incompetent but is simply being modest. Understanding norms can also help you change your behavior to better fit in to certain social situations. For example, an American businessperson working in Japan, where a considerate conversational style is often the norm, might want to refrain from interrupting others and to avoid any behavior typically associated with a competitive conversational style.

Competitive versus Considerate Conversational Norms

Take a look at the following transcript. It shows the actual discussion of a student team and has not been edited for grammar or completeness. As you read, think about how you would characterize the discussion norms that these speakers seem to hold.

Mark: Okay. Here [are] my thoughts on organization. This is what I call “pre-applying.” Stuff you want to have down before you apply.

Natalie: Before you graduate.

Mark: Yeah. And then the next section is applying. Then is the interview process, what to do, how to act. And then I thought maybe the last question would be “after the interview.”

Keith: Okay, I’m not sure I buy into a pre-applying section like that. “Pre” implies a time issue, but these [are] done before you go. “Pre” is incorporating everything except the interview.

Mark: Okay, but I’m thinking about the process. . . .

Keith: Yeah, but do you think that should be like the way to organize the paper? You see, pre-applying, that seems to incorporate everything to me. Maybe you could say, um, “Curriculum Requirements,” “Deadlines.” Something like that, you know. . . .

Mark: No.

Keith: “Pre” is a meaningless title because it would be everything.

Mark: No, what . . .

Natalie: I think what Mark’s saying . . .

Keith: I understand, but see, having it all under the title of “pre-applying” doesn’t make sense.

Mark: When I think about applying, I’m thinking about, July first is when I turn in my materials.

Keith: I understand exactly what you’re saying, but I don’t understand why you need that under that title of “pre-applying.”

Mark: I think it’s a natural process.

Keith: I’m suggesting we reword that whole thing.

Natalie: Could we say “Things that should be done prior to . . .”?

Keith: Find some other way of wording it because the way it’s worded right now doesn’t make any sense at all.

Natalie: Okay, what I’m saying is we could have “Things that should be done prior to the application process” and then “Things that can be done during the process.”

Keith: (talking over Natalie) We can stress . . .

Mark: (talking at the same time as Keith) But when I think “during” . . .

Mark and Keith both demonstrate a competitive conversational style in this exchange. They frequently interrupt each other (and Natalie) and often seem more concerned with making their own points than with listening to what the other has to say. Overall, Keith and Mark both tended to enjoy such exchanges, associating them with a high degree of involvement in the project. Many people find the back-and-forth of competitive conversations exciting and enjoy the challenge of scoring a point or winning others over to their side. In many ways, competitive conversations like this one resemble the types of debates you might see on TV programs such as The O’Reilly Factor or Hardball with Chris Matthews.

Unfortunately, although competitive conversations allow speakers to battle out ideas, speakers are not really involved in coming to a cooperative solution. For instance, in the preceding conversation, both Keith and Mark advocate for their own ideas without ensuring that they have heard the other’s counterposition. Keith states that he understands Mark, but he fails to convince Mark of this. The conversation would have been far more productive if Keith had told Mark “I understand your position to be X” and had given Mark a chance to confirm or deny this understanding. This strategy would have given Mark an opportunity to clarify his reasoning; furthermore, it would have assured him that he could stop arguing for his position and would have allowed him to listen more productively to Keith’s criticism.

Even worse, though, is that Natalie is having trouble entering the conversation. One of the problems with competitive conversational styles is that they are hierarchical: in other words, speakers who are perceived as having lower status on the team are more likely to be interrupted, ignored, or talked over. On this team, Natalie has consistently been less vocal than her teammates and less assertive when she does speak. As a consequence, her teammates have become accustomed to thinking of her as someone who does not have much to contribute — as someone with less influence than her teammates. Thus, even when she does speak, her teammates have a hard time hearing her: they talk over her and barely consider the suggestion she has made.

Natalie, of course, could be more assertive and speak more competitively, like her teammates. However, this tactic may be difficult for her: as someone out of place in competitive conversations, Natalie has probably been socialized to think of behaviors such as interrupting and talking over others as rude. Unless she has an exceptionally strong investment in the project, Natalie may prefer to stop participating rather than adopt a conversational norm that she finds offensive.

One of the biggest problems with competitive conversations is that they can shut down people who don’t share this style and thus can exclude some speakers’ ideas. Those who like competitive conversations may think that they are openly debating ideas, but in fact, they are likely hearing and discussing fewer ideas than they would if the team had adopted a more cooperative conversational style.

In contrast to competitive conversations, considerate conversations are characterized by a high degree of mutual support through questions and what is known as back-channeling: providing support through brief statements such as “yeah” and “uh-huh” or by nodding your head. As you read the following conversation excerpt of a team planning a Web site, note what specific strategies the speakers are using to create a considerate conversational environment:

Josh: What we need to do at this point is figure out what resources we need to have ready so that when we sit down with Front Page, we know what we’re going to put in the site.

Rose: Oh, okay. Well, we can do that right now.

Ming: Yeah.

Stacy: Yeah, ’cause like whatever paperwork we need I can pick up this weekend, and then, if you want, we can distribute it out so we can all think of different ways to do it.

Rose: Yeah.

Ming: You know, I was gonna ask . . .

Stacy: I can pick up all the paperwork Friday. (to Ming) Sorry.

Ming: I was gonna ask if she wanted it like the examples in the online book or like a corporate site. It’s 30 pages long.

Stacy: I don’t think we need to do all 30 pages.

Ming: That’s what I was askin’.

Rose: Just do like a miniature version?

Stacy: Yeah.

Josh: Yeah.

Ming: So do we want it like the online one? Because I wasn’t sure about that example.

Josh: I thought that’s what she wanted.

Rose: Should we ask?

One of the biggest differences between this conversation and the competitive example is that Stacy repairs her interruption of Ming halfway through by turning to him and saying “sorry.” This simple action gives Ming an opportunity to say what is on his mind. Other effective remarks for inviting silenced speakers to talk include “I’m sorry. What were you trying to say?” or “Ming, you were interrupted just a second ago. Did you have something else to add?”

Moreover, in this conversation, we see speakers acknowledging ideas by saying “yeah” and restating ideas rather than immediately tearing them down. We also see team members asking questions rather than always arguing for a particular point of view.

A considerate speaking style does not mean that people always have to agree with one another. In the following excerpt, note how Wes and Marissa are able to disagree even while maintaining a considerate communication style:

John: Well, it sounds like we were going to be addressing our proposal to oil companies, but now we’re doing something else?

Wes: I was thinking environmental agencies.

Marissa: Do you think we could do both? We could do like, we want to propose this to the environmental place so we can go with them to the oil companies? So we can tell them what we want to say to the companies?

Wes: Yeah, that could work. (pause) But one thing that I was thinking, the proposal would be stronger if it was just one thing.

Marissa: I just don’t want to lose that focus on the companies themselves.

John: So like make oil companies an indirect audience? A secondary audience?

Marissa: Yeah. (to Wes) You think it’s too much to do both?

Wes: Yeah, kinda.

This group eventually ends up agreeing with Wes that the proposal would be stronger with a single, clearly defined audience. What is noteworthy here is that even though Wes and Marissa are disagreeing, they still display a considerate conversational style. Before pointing out problems with Marissa’s idea, Wes acknowledges that “that could work.” This acknowledgment, as well as John’s later restatement of Marissa’s idea, most likely helps Marissa accept Wes’s criticism that she is proposing “too much.” Moreover, Marissa “checks in” with Wes by restating his idea and asking if she has understood correctly. This restatement lets Wes know that he was heard and invites him to elaborate on what he thinks.

Competitive speakers often have difficulty providing positive acknowledgment to their teammates and may even feel that all the agreement and “checking in” in the preceding two conversations sound silly. However, to speakers who have more considerate conversational norms, such agreement is necessary to an effective group, and those who fail to provide it appear self-centered or egotistical.

Competitive speakers can adjust their conversational style, although they may find it frustrating to do so. In fact, Wes (in a later interview) explains how he deliberately curbed some of his competitive instincts:

Wes: I wanted to say, “No, we can’t do both!” That’s not going to work. I mean, oil companies aren’t gonna adopt solar energy unless they’ve gone insane! I wanted to say that. But I had to think of how to say it that didn’t make her argument sound absurd because I didn’t want to do that.

Later on in the interview, Wes further acknowledged that he was trying to avoid “winning” an argument just based on his conversational style:

Wes: It’s a bad habit I have, but when I want people to do something, I usually try to just keep talking until they finally agree with me. I was trying not to do that here, but it was frustrating. It was slow.

Wes’s efforts to avoid making his teammates defensive seem to have paid off: at the end of this project, everyone on the team (including Wes) reported being highly satisfied with the way the group had worked together. Moreover, although Wes stated several times that he found the debate over their proposal’s audience frustrating, his teammates found the discussion useful:

Interviewer: Do you think this discussion was a productive one?

John: Very.

Interviewer: Why’s that?

John: Everybody’s just like getting their ideas out and just trying to get a feel for what are we going to do. We figured out what we wanted to talk about in this conversation. So, yeah, it was a very productive day.

Even though considerate conversation styles generally are good support for constructive conflict, in some cases they can interfere with teamwork if team members feel that they always have to wait for an invitation to speak or are so concerned with preserving people’s feelings that they hold back on ideas. The goal is to foster a group style that allows everyone to feel that he or she can contribute while still keeping the team focused on finding an effective solution.

How Can Competitive Speakers Adopt a More Considerate Style?

The following strategies — which are good strategies for any team to follow — help mitigate the silencing effects of competitive conversations:

- Repeat back or restate ideas before disagreeing with them.

- Repair interruptions and other competitive behaviors. Competitive speakers may find themselves unconsciously interrupting, raising their voices, or speaking over someone. When this happens, they (or anyone else on the team) can repair these actions by turning to the silenced person and saying “I’m sorry. You were saying?” or “David, you were interrupted just a second ago. Did you have something else to add?” or just “Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt.”

- Check in with quiet speakers. Every so often, the project manager or other team member should check in with anyone who has not spoken recently by saying “Do you have any thoughts?”

- Pay attention to body language. Watch the nonverbal behaviors of your teammates. If any of your teammates start to say something but stop, extend their arm or hand toward the center of the group, or lean far forward in their seat, they may be attempting to enter into the conversation. Whenever your teammates display these types of behaviors, invite them to speak by saying something like “Julie, you look like you have something to say.”

- Engage in uncritical brainstorming. In uncritical brainstorming, teams set aside a limited period (say 10 minutes) during which no criticisms of ideas are allowed. Team members can build on one another’s ideas and ask questions but not point out flaws. The goal of this brainstorming period is to get as many ideas as possible on the table and see what is good about these ideas before finding fault with them.

How Can Considerate Speakers Adjust to Competitive Conversations?

If you are a considerate speaker, you may have to deal with situations in which competitive speech is the norm. Rather than giving up on participating or becoming angry at your teammates, you can use the following strategies for getting your ideas across:

- Learn how to prevent or forestall interruptions. To stop a competitive speaker from interrupting, you can use gestures while speaking, such as extending your arm forward or holding up your hand like a stop sign. Such gestures tell others that you are not done yet and have more to say. Simple stock phrases, such as “I’m not finished yet” or “One minute please,” can also be good ways to stop interruptions.

- Speak within the first five minutes of a meeting. Another nonaggressive strategy for dealing with competitive conversations is to get people accustomed to thinking of you as having something important to say. Louisa Ritter, Telecommunications Chief of Staff for a major investment firm, states, “The longer it goes without you saying something, the longer people are going to ignore you, and by the time you do speak up, people are just going to think you’re peripheral to the meeting” (Commonwealthclub, 2003).

- Find gentle ways to interrupt. Ultimately, you may need to learn how to interrupt if you want to have any hope of getting your say in a competitive conversation. Strategies such as humor can help you. For instance, you might try raising your hand and waving it wildly both to make people laugh and to pause the conversation. You might also learn how to time your interruptions so that they do not seem rude. Cathy G. Lanier, President of Technology Solutions, Inc., states, “I’m an excellent interrupter. . . . I tend to go with the ebb and flow of meetings and am pretty good at timing my interruptions so they don’t seem overly rude or pushy” (Sherman, 2005).

Self-Promoting versus Self-Deprecating Speech

Consider the following comments that students made in final interviews about their team experiences. What do you think about each speaker?

A. I found that [my team] kept looking toward me. Whenever we would get bogged down, when something wasn’t right, it seemed to invariably come to me to be fixed.

B. Well, I handled all the, uh, you know, I handled all the Web site. Basically, I built the entire Web site myself. . . . I’m the type of person, whether I fully know how to understand and know how to do it or not, I’ll figure it out. I’ll go ahead and take it, take the ball and go with it.

C. To be honest with you, I realized that the scope of this project wasn’t large enough for me, so I kind of slacked off on some little things.

D. I can usually go into a class and kind of tell who’s, you know, who’s gonna do well, who’s not gonna do well. Umm, who’s a little quicker. Those students, I’ve had some of them before in other classes, and they’re kind of like the lower end of the curve.

E. Probably Stephen made the most valuable contribution ’cause he came up with the main idea, and I know that I would never have been able to come up with that.

F. I did learn quite a bit about computers, and I’m saying that only because I knew so little about that beforehand. But you know, I am learning. I’m having problems publishing, but I feel I have a grasp on them.

G. I kind of know how to do the Web site, but I still have to have people to help me. The directions Charlotte gave me are good, but when there wasn’t a direction on how to fix it, when you have something wrong, I would go outside the group.

H. I mean, John and Neal are really, really good at writing reports. I would be at the bottom of that list because I’m, I’m not as good at, you know, putting things together. Umm, I feel, I feel confident in creating a report. I just think that they’re better at it.

Comments A through D are examples of self-promotional speech, while comments E through H are examples of self-deprecating speech. Self-promotional speech is characterized by occasionally aggressive displays of confidence and criticism of others in order to make oneself look better. Self-deprecating speech is characterized by exaggerated displays of modesty and talking about one’s own shortcomings. Both types of speech can cause major problems in groups.

Note how self-promotional talk led the speaker in comment C to see certain aspects of the project as beneath him and the speaker in comment D to view certain people as less worthy of respect. Self-promotional talk can also lead speakers to hoard certain parts of the project as their own and to exclude others from any input: this was the case with the speaker in comment B. Thus, self-promotional talk often leads to hierarchical teams in which some work is perceived as more valuable than other work and people at the top of the hierarchy can see themselves as immune to the criticisms and comments of others. This type of mind-set is so counterproductive that NASA engineers who were surveyed about problems with teams rated the statement “Some members believe that their technical status insulates their opinions from evaluation by other team members” as the number one behavior contributing to team problems (Nowaczyk, 1998).

In settings where self-promotional talk is the norm, people can be reluctant to admit weakness or ask one another for help. In student teams, this can lead to projects in which one student takes on too much but never lets the rest of the team know that the project is in danger until the end, when it is too late. In other settings, the consequences can be even higher. For instance, at one major oil company’s offshore oil rigs, self-promotional norms that prized heroic accomplishments and disdained any show of weakness encouraged workers to hide mistakes; consequently, many systemic safety issues never came to light because workers did not feel comfortable discussing them. When this company purposefully tried to change the communication norms to develop an atmosphere in which workers felt comfortable productively discussing mistakes and learned to respond to criticism nondefensively, accidents were reduced by 84 percent, while productivity, efficiency, and reliability all increased (Ely & Meyerson, 2007).

Self-deprecating talk may not have such dire consequences, but it can hurt teammates’ status on teams and can interfere with team productivity because it takes attention off the problem and puts it on the person and his or her abilities. This is perhaps most evident in comments E and H, in which the speakers talk excessively about how much more inferior their skills are than their teammates’. A teammate listening to this might question whether this person can be trusted with important work — and might even wonder if the speaker is indirectly asking to be given a free ride on the project. Creating this kind of doubt in your teammates’ minds does nothing to help the project or yourself.

Even the other two self-deprecating comments (F and G) might make team members wonder whether the speaker is asking for reassurance — in other words, fishing for compliments. Many team members find such comments frustrating because they would rather spend their energy getting to work rather than trying to reassure and bolster the confidence of others.

Both self-promoting talk and self-deprecating talk interfere with team progress, and you should work to avoid both. Be honest about your shortcomings without focusing on them. For instance, if you are assigned a task that you are unfamiliar with, you can state, “I haven’t done this before, but I’m looking forward to the challenge” or “I should be able to do that, but I want someone to look over my work just in case.” Such statements suggest that you have confidence in yourself without overselling your abilities.

Action-Oriented versus Holistic Problem-Solving Styles

The following comments are by students who exhibit preferences for two different problem-solving styles:

Bill: That whole first day was not productive at all. That was us spinning on our toes until the very end. The whole session was just kind of randomly hashing out what we were going to do and not actually getting anything done. That’s the worst thing for me, when we just talk and talk and talk and nothing happens, you know. It’s like just do it! I have nothing against going off and talking about stuff. But we didn’t have time for that. We needed to start working because it was supposed to be a large-scale project and it was something that was supposed to take the whole semester and it was something that we needed to start on.

Krista: I just don’t like to just rush stuff. I don’t like to just throw anything together, and that’s what they were wanting to do. Like I said, the rest of the group was so determined to just get it done. I felt like I was the one who kept going “No, we need to go back because if we don’t include everything in there he wants, he’s gonna send it back. So regardless if you sit here trying to rush it, we’re going to have to do it over anyway.” I felt like all this was new to me, and I knew we had a time limit, but I wanted to learn too and not just do something.

Bill’s comments show that he favors an action-oriented problem-solving approach, in which team members jump into the details of the problem and immediately start working on a solution. By contrast, Krista appears to favor a holistic problem-solving approach, in which team members begin by considering the entire problem as a whole and refrain from proposing solutions until the problem is completely understood. Action-oriented problem solvers tend to concentrate on solving one piece of the puzzle at a time, whereas holistic problem solvers make sure that the end goal is always in sight.

Those who favor an action-oriented problem-solving style frequently grow impatient with holistic problem solvers and see their slowness in getting started as reflecting insecurity with the details. Being an action-oriented problem solver, Bill expresses his frustration that the group is not getting anything done. Even though the team is at the start of a semester-long project, he wants to see the group take some action.

Those favoring holistic problem solving worry that the action-oriented approach will miss the big picture — for instance, by creating a product that works but that nobody wants to buy. Krista expresses this concern when she claims that her teammates are going to put together a project that the instructor will return and ask them to do over. She wants to ensure that the group understands the requirements and end goals before they begin putting the project together.

Action-oriented problem solvers tend to learn by tinkering and trying out different solutions. This approach works well on small problems but is often less suitable for large, complex problems that require the coordination of several people because the action-oriented approach can lose sight of the big picture. Holistic problem solvers often take longer to arrive at a solution because they spend more time planning up front before they tackle the details of a problem; however, they are more likely to get the correct solution once they get started.

How Can Our Team Balance Different Problem-Solving Styles?

Both the action-oriented and the holistic problem-solving styles are important and necessary on a smoothly functioning team. However, some types of problems are more appropriately addressed by one style than the other. Your team’s goal should be to try to balance these styles. The following suggestions will help you use these styles strategically:

- The best time for holistic problem solving is at the beginning of the project. When the group is in the early stages of the project, particularly a large project, spend some time making sure that everyone shares the same goals and that the team explores all of its options. Action-oriented problem solvers simply need to be patient at this stage. If you are concerned about deadlines, you might sketch out a brief project schedule and calculate how much time the team can afford to spend on holistic problem solving. Most holistic problem solvers will be able to switch gears and jump into the details when they feel that the time has come.

- Be patient and strategic. A particular problem-solving orientation may be better suited to certain tasks than to others. For instance, the group may benefit if the project manager has a more holistic problem-solving style and those working on smaller parts of the project have a more action-oriented style. Remember that differences in problem-solving styles are just that — differences — and do not reflect a person’s underlying ability.

- Refer to the team charter or task schedule to resolve conflicts. The first two items on your team charter (see Chapter 3, “Getting Started with the Team Charter”) should refer to team goals. To remind action-oriented problem solvers of the ultimate goals of the project, holistic problem solvers can refer to the goals that the team agreed on at the outset of the project. Likewise, action-oriented problem solvers can refer to the task schedule to make sure that the project stays on schedule and doesn’t get derailed by too many “big picture” conversations (especially when those conversations occur near the end of the project).

Gender and Communication Norms

As you read about the norms in Table 7.1, you may have thought that some of them were more characteristic of men and others more characteristic of women. Such observations may make you uncomfortable since they can lead to stereotyping. However, gender differences are worth discussing because gender influences not only how we act but also how we are perceived — and thinking about gender and communication can help us appreciate how difficult it can be to adapt to certain communication norms.

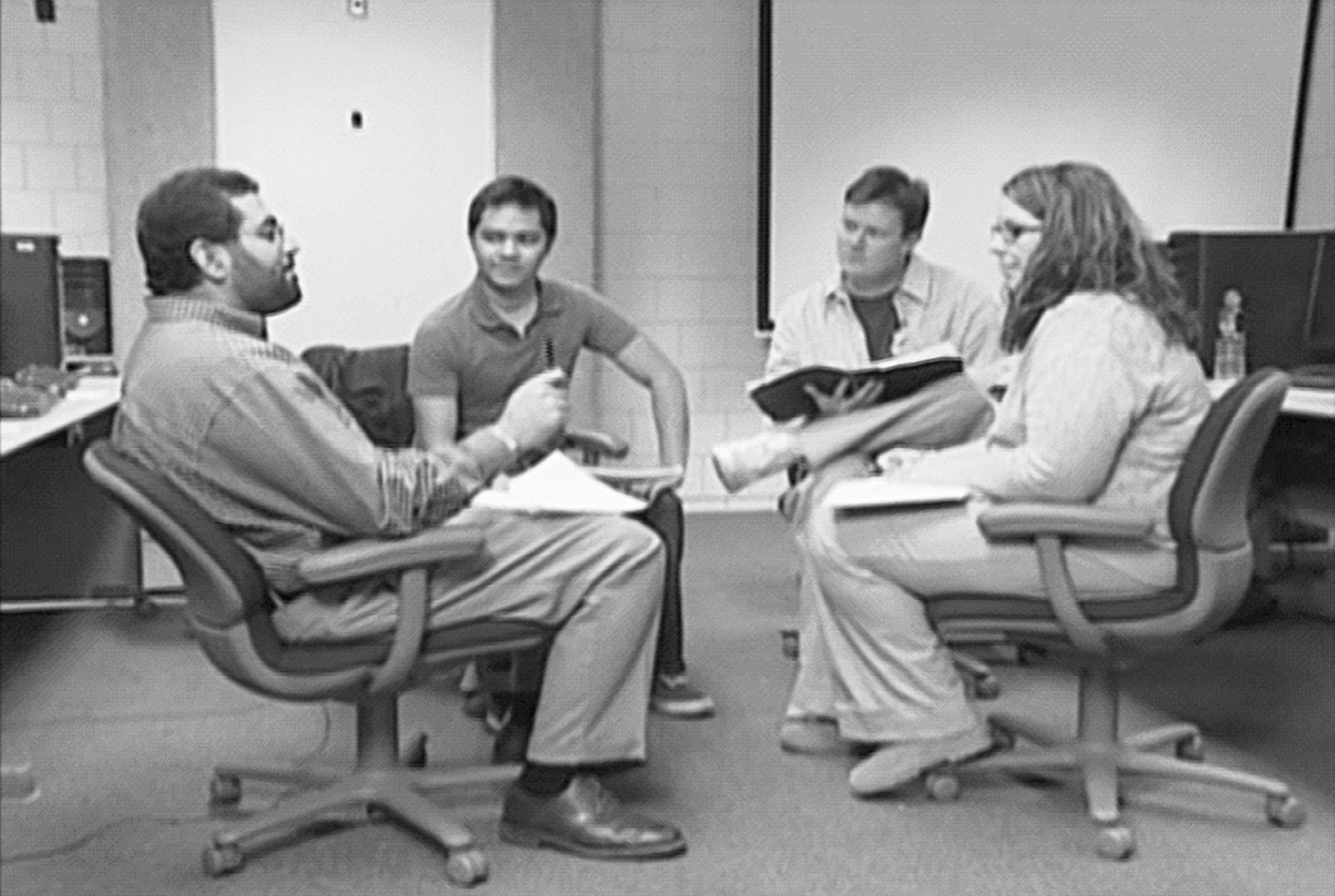

An easy way to see how gender socialization impacts communication norms is to look at body language. Take a moment to look around a classroom, lab, study area, or other public place. Can you identify differences in how men and women sit? Men typically take up more space when they sit by leaning back in their seats, sitting with legs stretched apart and extending their arms. By contrast, women tend to take up less room when they sit by sitting with knees touching and keeping their arms close to their bodies. Figure 7.4, taken from Team Video 3, illustrates some of these gender-typical differences in body language.

The men in this photograph occupy more physical space and are more likely to lean away from the group than does the one woman. Jamaal, in the foreground, leans back in his chair while extending his arm out to the group; Jim has his arm out to the side and leans slightly forward; Don places one foot across his knee (a position that men use far more frequently than do women, who are more likely to cross their legs at the knee). In contrast to the men, Tonya keeps her body close to her chair; her legs are close to each other, almost touching at the knees; and her arms are close to the center of her body. Even her hands are touching each other.

Of course, there is nothing right or wrong, or good or bad, about these different ways of sitting — but they do illustrate different norms, even different rules, governing men’s and women’s interpersonal behaviors. For example, if a woman sat like one of the men in the picture, she might be labeled as “unfeminine” for mimicking the body language of a male peer. Have you ever observed a woman behave in a way that you found unfeminine or a man behave in a way that you found unmanly? What specific behavior or action made you draw this conclusion? How would this behavior have appeared if someone of the opposite gender had done the exact same thing?

Not only do men and women have different norms that govern what they consider acceptable interpersonal behavior, but there are also social rules that affect how others perceive them if they violate these norms. As a consequence, a woman who engages in behaviors typically associated with men may be perceived in much more unflattering ways than a man would be if he did the same thing. In fact, one recent study of negotiation behaviors tested this hypothesis by asking managers to look at videotapes of men and women, all of whom were following the same script, negotiate for a higher salary. The managers perceived the female negotiator as less likable and more difficult to work with than the male negotiator, despite the fact that both had uttered the same words and followed the same nonverbal communication cues (Bowles et al., 2007).

In other words, because of these social rules, women may not be able to figure out the best way to behave by observing men’s behavior, and vice versa. Thus, women who find themselves in a competitive discussion (which tends to be a more masculine communication norm) may need to find nonaggressive ways to negotiate this conversational environment without necessarily imitating men’s competitive strategies. Likewise, men may need to adapt to considerate conversational styles in ways that do not necessarily mimic “feminine” strategies.

Because the same behavior can be perceived differently depending on who is saying it, we can’t always expect other people to adjust their communication styles to what we personally perceive as normal. Although all communication styles have pros and cons, some are more exclusionary than others in that not everybody is equally free to engage in these behaviors. Some communication styles will produce more negative social consequences for some groups than for others.

A number of researchers have studied the impact of gender and ethnicity on communication norms:

- Men are more likely than women to have competitive speaking norms and to self-promote (Ely & Meyerson, 2007; Fletcher, 1999; McIlwee & Robinson, 1992; Rudman, 1998; Tannen, 1990; West & Zimmerman, 1983; Wolfe & Powell, 2006).

- Women who self-promote are perceived more negatively than are men who self-promote (Bowles et al., 2007; Rudman, 1998).

- Women are more likely than men to use self-deprecating speech, a norm that is thought to hurt women in competitive workplaces (Ingram & Parker, 2002; Kitayama et al., 1997; Rudman, 1998; Tannen, 1990; Wolfe & Powell, 2006).

- African American women are less likely to be silenced by interruptions and other behaviors characteristic of competitive discussions than white women are (hooks, 1989; Kochman, 1981).

- Women are more likely to prefer online discussions (discussions that take place entirely via computer) than men are, although this preference seems to vary by ethnicity (Lind, 1999; Wolfe, 2000). Women in male-dominated teams report more satisfaction with online discussions than with face-to-face discussions (Lind, 1999), possibly because it is not possible to interrupt or talk over someone online.

- People from Asian cultures tend to favor considerate speaking norms; men who have been successful in American and European settings often have difficulty adjusting to professional environments in countries such as Japan (De Mente, 2002; Howden, 1994).

- People from the Northeast self-report more competitive communication behaviors than do people from the Midwest (Sigler, 2005).

- Men are slightly more likely than women to prefer action-oriented problem-solving styles, and women are slightly more likely to prefer holistic styles (Woodfield, 2000).

Work Cited

Bowles, H. R., Babcock, L., & Lai, L. (2007). Social incentives for gender differences in the propensity to initiate negotiations: Sometimes it does hurt to ask. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 84–103.

Commonwealthclub. (2003). Women in business: Lessons learned. Retrieved August 13, 2008, from http://www.commonwealthclub.org/archive/03/03-08women-speech.html.

Cordero, R., DiTomaso, N., & Ferris, G. F. (1996). Gender and race/ethnic composition of technical work groups: Relationship to creative productivity and morale. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 13, 205–221.

De Mente, B. L. (2002). Sincerity, Japanese style. Excerpted from Japanese etiquette & ethics in business. Retrieved August 13, 2008, from http://www.apmforum.com/columns/boye49.htm.

Ely, R. J., & Meyerson, D. (2007). Unmasking manly men: The organizational reconstruction of men’s identity (No. 07-054). Boston: Harvard Business School.

Fletcher, J. K. (1999). Disappearing acts: Gender, power, and relational practice at work. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

hooks, b. (1989). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Boston: South End Press.

Howden, J. (1994). Competitive and collaborative communicative style: American men and women, American men and Japanese men. Intercultural Communication Studies, 4(1), 49–58.

Ingram, S., & Parker, A. (2002). Gender and modes of collaboration in an engineering classroom: A profile of two women on student teams. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 16(1), 33–68.

Kim, H.-J. (2003). A study of compliments across cultures. Paper presented at the eighth annual meeting of the Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics. Retrieved August 1, 2008, from http://www.paaljapan.org/resources/proceedings/PAAL8/pdf/pdf015.pdf.

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., Matsumoto, H., & Norasakkunki, V. (1997). Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: Self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1245–1267.

Kochman, T. (1981). Black and white styles in conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lind, M. R. (1999). The gender impact of temporary virtual work groups. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, 42(4), 276–285.

McIlwee, J. S., & Robinson, J. G. (1992). Women in engineering: Gender, power, and workplace culture. Albany: SUNY Press.

Nowaczyk, R. H. (1998). Perceptions of engineers regarding successful engineering team design (No. NASA/CF-1998-206917 ICASE Report No. 98-9). Hampton, VA: Institute for Computer Applications in Science and Engineering.

Rudman, L. (1998). Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counterstereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 629–645.

Sherman, A. (2005). Speak up: Is interrupting a good business tactic or just plain rude? Entrepreneur. Retrieved October 7, 2008, from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0DTI/is_/ai_n15777261.

Sigler, K. A. (2005). A regional analysis of assertiveness. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association. Retrieved June 27, 2008, from http://www.allacademic.com/meta/p14806_index.html.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. New York: HarperCollins.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1983). Small insults: A study of interruptions in cross-sex conversations between unacquainted persons. In B. Throne, C. Kramarae, & N. Henley (Eds.), Language, gender, and society (pp. 103–118). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Wolfe, J. (2000). Gender, ethnicity, and classroom discourse: Communication patterns of Hispanic and white students in networked classrooms. Written Communication, 17(4), 491–519.

Wolfe, J., & Powell, E. (2006). Gender and expressions of dissatisfaction: A study of complaining in mixed-gendered student work groups. Women and Language, 29(2), 13–21.

Woodfield, R. (2000). Women, work, and computing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.