10.19

932

from Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

James Barrat

James Barrat (b. 1960) is a documentary filmmaker whose work has appeared on National Geographic, Discovery, and PBS. The selection here is from Chapter 1 of Barrat’s book, Our Final Invention, which is the product of his long fascination with robots and artificial intelligence. In it he asks the questions, “Will machines naturally love us and protect us? Should we bet our existence on it?”

I’ve written this book to warn you that artificial intelligence could drive mankind into extinction, and to explain how that catastrophic outcome is not just possible, but likely if we do not begin preparing very carefully now. You may have heard this doomsday warning connected to nanotechnology and genetic engineering, and maybe you have wondered, as I have, about the omission of AI in this lineup. Or maybe you have not yet grasped how artificial intelligence could pose an existential threat to mankind, a threat greater than nuclear weapons or any other technology you can think of. If that’s the case, please consider this a heartfelt invitation to join the most important conversation humanity can have.

Right now scientists are creating artificial intelligence, or AI, of ever-

Scientists are aided in their AI quest by the ever-

Now, it is an anthropomorphic fallacy to conclude that a superintelligent AI will not like humans, and that it will be homicidal, like the Hal 9000 from the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, Skynet from the Terminator movie franchise, and all the other malevolent machine intelligences represented in fiction. We humans anthropomorphize all the time. A hurricane isn’t trying to kill us any more than it’s trying to make sandwiches, but we will give that storm a name and feel angry about the buckets of rain and lightning bolts it is throwing down on our neighborhood. We will shake our fist at the sky as if we could threaten a hurricane.

933

seeing connections

May 2007, World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov loses to the IBM Deep Blue chess computer. It is the first time in history that a computer defeats a reigning world champion.

January 2011, IBM’s Watson computer wins Jeopardy!, defeating previous champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter.

What conclusions should we draw from these accomplishments by robots?

Are they a sign of intelligence?

5 It is just as irrational to conclude that a machine one hundred or one thousand times more intelligent than we are would love us and want to protect us. It is possible, but far from guaranteed. On its own an AI will not feel gratitude for the gift of being created unless gratitude is in its programming. Machines are amoral, and it is dangerous to assume otherwise. Unlike our intelligence, machine-

934

And that brings us to the root of the problem of sharing the planet with an intelligence greater than our own. What if its drives are not compatible with human survival? Remember, we are talking about a machine that could be a thousand, a million, an uncountable number of times more intelligent than we are — it is hard to overestimate what it will be able to do, and impossible to know what it will think. It does not have to hate us before choosing to use our molecules for a purpose other than keeping us alive. You and I are hundreds of times smarter than field mice, and share about 90 percent of our DNA with them. But do we consult them before plowing under their dens for agriculture? Do we ask lab monkeys for their opinions before we crush their heads to learn about sports injuries? We don’t hate mice or monkeys, yet we treat them cruelly. Superintelligent AI won’t have to hate us to destroy us.

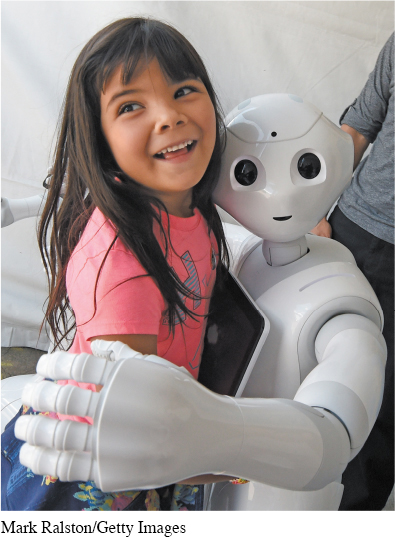

Yaretzi Bernal, six, gets a hug from “Pepper,” the emotional robot on display during the finals of the DARPA Robotics Challenge at the Fairplex complex in Pomona, California, on June 5, 2015. The competition had twenty-

What aspects of Pepper’s design would make the robot effective in responding to natural and man-

After intelligent machines have already been built and man has not been wiped out, perhaps we can afford to anthropomorphize. But here on the cusp of creating AGI, it is a dangerous habit. Oxford University ethicist Nick Bostrom puts it like this:

A prerequisite for having a meaningful discussion of superintelligence is the realization that superintelligence is not just another technology, another tool that will add incrementally to human capabilities. Superintelligence is radically different. This point bears emphasizing, for anthropomorphizing superintelligence is a most fecund source of misconceptions.

Superintelligence is radically different, in a technological sense, Bostrom says, because its achievement will change the rules of progress — superintelligence will invent the inventions and set the pace of technological advancement. Humans will no longer drive change, and there will be no going back. Furthermore, advanced machine intelligence is radically different in kind. Even though humans will invent it, it will seek self-

Therefore, anthropomorphizing about machines leads to misconceptions, and misconceptions about how to safely make dangerous machines lead to catastrophes. In the short story, “Runaround,” included in the classic science-

935

A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

A robot must obey any orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

10 The laws contain echoes of the Golden Rule (“Thou Shalt Not Kill”), the Judeo-

Asimov was generating plot lines, not trying to solve safety issues in the real world. Where you and I live his laws fall short. For starters, they’re insufficiently precise. What exactly will constitute a ‘‘robot” when humans augment their bodies and brains with intelligent prosthetics and implants? For that matter, what will constitute a human? “Orders,” “injure,” and “existence” are similarly nebulous terms.

Tricking robots into performing criminal acts would be simple, unless the robots had perfect comprehension of all of human knowledge. “Put a little dimethylmercury in Charlie’s shampoo” is a recipe for murder only if you know that dimethylmercury is a neurotoxin. Asimov eventually added a fourth law, the Zeroth Law, prohibiting robots from harming mankind as a whole, but it doesn’t solve the problems.

Yet unreliable as Asimov’s laws are, they’re our most often cited attempt to codify our future relationship with intelligent machines. That’s a frightening proposition. Are Asimov’s laws all we’ve got?

I’m afraid it’s worse than that. Semiautonomous robotic drones already kill dozens of people each year. Fifty-

15 As I’ll argue, AI is a dual-

Understanding and Interpreting

Identify James Barrat’s central claim about why we need to be careful about our development of artificial intelligence (AI).

According to Barrat, what are the similarities and differences between human emotions and AI’s “drives”?

Explain what Barrat sees as the dangers of anthropomorphizing AI.

How does Barrat illustrate that the Three Laws of Robotics cannot manage the dangers posed by AI? How effective is his use of fictional examples to support real-

life claims? Although he does not state it directly in this excerpt, what actions do you think Barrat would likely propose we take to avoid the dangers he sees? What evidence from this section supports your inference?

936

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What does Barrat do throughout this excerpt to establish his own ethos on the topic of robots and artificial intelligence?

Reread the first paragraph of this excerpt and focus on Barrat’s diction. What is the effect of his word choice and what is his likely purpose in beginning this section in this way?

Look closely at paragraph 3, in which Barrat traces a possible future in the development of artificial intelligence. How does he use language choices to make this future feel inevitable and dangerous?

In paragraph 6, Barrat uses analogies to support his argument about the ways that AI will act toward humans. Explain the analogies and evaluate how effective they are in building his argument.

What is the difference between “intelligence” and “superintelligence” (pars. 7–

8), and how does Barrat use the meaning of the second term to serve his argument? Barrat ends this excerpt with a reference to nuclear fission. Evaluate the effectiveness of this reference as his conclusion to the piece.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Barrat says in paragraph 5 that “[m]achines are amoral, and it is dangerous to assume otherwise.” Do you agree or disagree with that statement? Why? What are possible dangers that we could face from AI that Barrat does not include in this excerpt?

The Greek myth of Pandora’s Box is often cited when science appears to be unleashing technologies that we may not be able to fully control. Research the story of Pandora and explain its connection to AI and to at least one other scientific development in history.

As you may have read in the introduction to this Conversation, Stephen Hawking, one of the most respected scientists in the world, believes that a takeover by AI is a real danger to humanity, but others are less pessimistic. Conduct additional research and write an argument in which you make and support a claim about the reasonable fears humans ought to have about AI.