5.9

162

Eveline

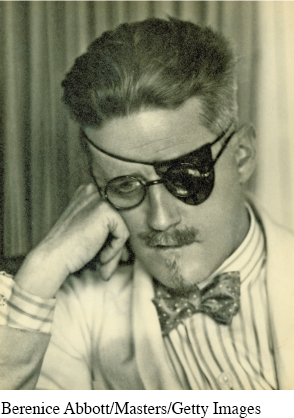

James Joyce

James Joyce (1882–

She sat at the window watching the evening invade the avenue. Her head was leaned against the window curtains and in her nostrils was the odour of dusty cretonne.1 She was tired.

Few people passed. The man out of the last house passed on his way home; she heard his footsteps clacking along the concrete pavement and afterwards crunching on the cinder path before the new red houses. One time there used to be a field there in which they used to play every evening with other people’s children. Then a man from Belfast bought the field and built houses in it — not like their little brown houses but bright brick houses with shining roofs. The children of the avenue used to play together in that field — the Devines, the Waters, the Dunns, little Keogh the cripple, she and her brothers and sisters. Ernest, however, never played: he was too grown up. Her father used often to hunt them in out of the field with his blackthorn stick; but usually little Keogh used to keep nix2 and call out when he saw her father coming. Still they seemed to have been rather happy then. Her father was not so bad then; and besides, her mother was alive. That was a long time ago; she and her brothers and sisters were all grown up her mother was dead. Tizzie Dunn was dead, too, and the Waters had gone back to England. Everything changes. Now she was going to go away like the others, to leave her home.

Home! She looked round the room, reviewing all its familiar objects which she had dusted once a week for so many years, wondering where on earth all the dust came from. Perhaps she would never see again those familiar objects from which she had never dreamed of being divided. And yet during all those years she had never found out the name of the priest whose yellowing photograph hung on the wall above the broken harmonium3 beside the coloured print of the promises made to Blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque. He had been a school friend of her father. Whenever he showed the photograph to a visitor her father used to pass it with a casual word:

“He is in Melbourne now.”

5 She had consented to go away, to leave her home. Was that wise? She tried to weigh each side of the question. In her home anyway she had shelter and food; she had those whom she had known all her life about her. Of course she had to work hard, both in the house and at business. What would they say of her in the Stores when they found out that she had run away with a fellow? Say she was a fool, perhaps; and her place would be filled up by advertisement. Miss Gavan would be glad. She had always had an edge on her, especially whenever there were people listening.

163

“Miss Hill, don’t you see these ladies are waiting?”

“Look lively, Miss Hill, please.”

She would not cry many tears at leaving the Stores.

Mary Plunkett is an Irish artist, graphic designer, and printmaker who specializes in letterpress. She created these images based on the story “Eveline.”

But in her new home, in a distant unknown country, it would not be like that. Then she would be married — she, Eveline. People would treat her with respect then. She would not be treated as her mother had been. Even now, though she was over nineteen, she sometimes felt herself in danger of her father’s violence. She knew it was that that had given her the palpitations. When they were growing up he had never gone for her like he used to go for Harry and Ernest, because she was a girl but latterly he had begun to threaten her and say what he would do to her only for her dead mother’s sake. And no she had nobody to protect her. Ernest was dead and Harry, who was in the church decorating business, was nearly always down somewhere in the country. Besides, the invariable squabble for money on Saturday nights had begun to weary her unspeakably. She always gave her entire wages — seven shillings — and Harry always sent up what he could but the trouble was to get any money from her father. He said she used to squander the money, that she had no head, that he wasn’t going to give her his hard-

164

10 She was about to explore another life with Frank. Frank was very kind, manly, open-

“I know these sailor chaps,” he said.

One day he had quarrelled with Frank and after that she had to meet her lover secretly.

The evening deepened in the avenue. The white of two letters in her lap grew indistinct. One was to Harry; the other was to her father. Ernest had been her favourite but she liked Harry too. Her father was becoming old lately, she noticed; he would miss her. Sometimes he could be very nice. Not long before, when she had been laid up for a day, he had read her out a ghost story and made toast for her at the fire. Another day, when their mother was alive, they had all gone for a picnic to the Hill of Howth. She remembered her father putting on her mother’s bonnet to make the children laugh.

Her time was running out but she continued to sit by the window, leaning her head against the window curtain, inhaling the odour of dusty cretonne. Down far in the avenue she could hear a street organ playing. She knew the air. Strange that it should come that very night to remind her of the promise to her mother, her promise to keep the home together as long as she could. She remembered the last night of her mother’s illness; she was again in the close dark room at the other side of the hall and outside she heard a melancholy air of Italy. The organ-

165

15 “Damned Italians! coming over here!”

Look at this painting, Girl at a Window Reading a Letter, by Jan Vermeer. It was created around 1659, over two hundred years before this short story was written.

As she mused the pitiful vision of her mother’s life laid its spell on the very quick of her being — that life of commonplace sacrifices closing in final craziness. She trembled as she heard again her mother’s voice saying constantly with foolish insistence:

“Derevaun Seraun! Derevaun Seraun!4”

She stood up in a sudden impulse of terror. Escape! She must escape! Frank would save her. He would give her life, perhaps love, too. But she wanted to live. Why should she be unhappy? She had a right to happiness. Frank would take her in his arms, fold her in his arms. He would save her.

She stood among the swaying crowd in the station at the North Wall. He held her hand and she knew that he was speaking to her, saying something about the passage over and over again. The station was full of soldiers with brown baggages. Through the wide doors of the sheds she caught a glimpse of the black mass of the boat, lying in beside the quay5 wall, with illumined portholes. She answered nothing. She felt her cheek pale and cold and, out of a maze of distress, she prayed to God to direct her, to show her what was her duty. The boat blew a long mournful whistle into the mist. If she went, tomorrow she would be on the sea with Frank, steaming towards Buenos Ayres. Their passage had been booked. Could she still draw back after all he had done for her? Her distress awoke a nausea in her body and she kept moving her lips in silent fervent prayer.

20 A bell clanged upon her heart. She felt him seize her hand:

“Come!”

All the seas of the world tumbled about her heart. He was drawing her into them: he would drown her. She gripped with both hands at the iron railing.

“Come!”

No! No! No! It was impossible. Her hands clutched the iron in frenzy. Amid the seas she sent a cry of anguish.

25 “Eveline! Evvy!”

He rushed beyond the barrier and called to her to follow. He was shouted at to go on but he still called to her. She set her white face to him, passive, like a helpless animal. Her eyes gave him no sign of love or farewell or recognition.

166

Understanding and Interpreting

“Eveline” focuses on the central character’s decision-

making process. What are the conflicting forces pulling Eveline in different directions? Identify and discuss at least three. What is the nature of the relationship Eveline has with her father? In what ways has it changed over time?

Eveline thinks of Frank in fairly general terms:he is “very kind, manly, open-

hearted” (par. 10). What more specific information does James Joyce give us? What is it about Frank that appeals to Eveline? Joyce characterizes the existence of Eveline’s mother as “that life of commonplace sacrifices closing in final craziness” (par. 16). In what ways is Eveline influenced by her mother’s life? How does her perception of her mother’s experience affect the way Eveline thinks of marriage?

Is Eveline a victim of her time and place—

when opportunities for women were limited primarily to the domestic realm— or is she a victim of her own indecisive character? Or is she a combination of both? Support your response with reference to specific passages in the story as well as your knowledge of the time period. Critics of “Eveline” disagree on their interpretations of the ending. Many conclude that Eveline’s inability to strike out with Frank is essentially accepting a life sentence as a housekeeper, even a servant, to her family. Others argue that in choosing to stay with her father, she defies Frank and thus shows at least the promise of becoming an independent woman. Which interpretation do you find most plausible? Support your response with references and specific passages from the story.

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What is the feeling Joyce conveys in the opening paragraph? What specific words and images contribute to that feeling? What is the effect of this paragraph’s being a third person observation while the rest of the story is told from Eveline’s perspective?

Much of “Eveline” centers on Eveline’s home life, both before and after her mother’s death. Joyce ends paragraph 2 with the sentence, “Now she was going to go away like the others, to leave her home.” He opens the next paragraph with the one word, “Home!” What does this repetition suggest about the meaning(s) of home to Eveline?

What symbolic value does Buenos Aires have in this story?

The last few paragraphs of the story takes place at the dock. Water is both literal (for example, the sea) and metaphoric (for example, “All the seas of the world tumbled about her heart”). How do these images contribute to our understanding of Eveline’s decision not to go with Frank?

Joyce explores the difficulty characters have in making important life decisions in several stories in Dubliners. In what ways does he demonstrate that Eveline is paralyzed or unable to take action? Pay attention to concrete descriptive details, connotative language, and imagery.

In this brief story, Joyce gives us glimpses of the past and the (imagined) future as well as the present. How do the past and future inform Eveline’s present thinking?

167

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Joyce writes that as “the evening deepened in the avenue” (par. 13), Eveline sits with two letters in her lap, one to her father, the other to her brother Harry. What do you imagine she has written in those letters? Try writing one and explain what in the story leads you to believe would be in the letter.

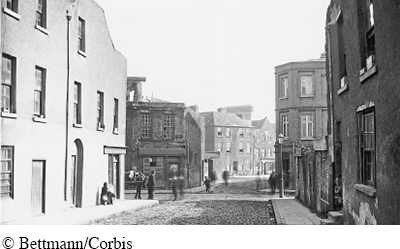

The photo below shows Dublin at about the time “Eveline” was set. How does the mood in this contemporary image of Dublin compare to the mood that Joyce creates in “Eveline”? What creates the mood in “Eveline” and in this photograph?

One of the themes Joyce explores in “Eveline” is the tension between responsibility (to family, to community) and the desire for individual freedom. To what extent do you find the way that tension plays out in today’s society similar to the way Eveline experienced it? In what ways have you experienced something similar to the choice that Eveline has to face?

Suppose that Eveline goes to Buenos Aires with Frank. Write a letter in her voice — a year later —describing her new life to her brother Harry. Think about how her audience would influence what she would say and how she would say it.