5.17

217

from Horace’s School: Redesigning the American High School

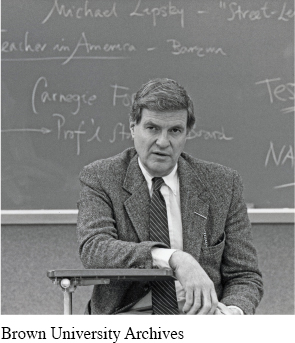

Theodore Sizer

Theodore Sizer (1932–

KEY CONTEXT This excerpt is taken from Sizer’s book Horace’s School: Redesigning the American High School (1997), which is the middle volume of a trilogy examining the state of American high schools and making suggestions for their improvement. In all three of the books, Sizer utilizes an unusual storytelling device that he calls “nonfiction fiction.” Sizer invents the character of Horace Smith, a teacher and school leader (and likely named as homage to Horace Mann) at a fictional school called Franklin High, which he says is a composite of a number of schools he visited. This excerpt begins with Sizer’s own personal account of a real classroom he visited, but ends with a fictionalized scene of Horace leading a faculty meeting. In his introduction, Sizer suggests that this device “carries its own sort of authenticity.”

When seeing schools as a visitor, I often ask to take a class. Sometimes teachers let me, though rarely with the brisk assent I received in a northeastern city high school when, on a moment’s notice, I was handed a ninth-

However, not every kid presented the essence of fourteenness. Of the twenty or so youngsters eyeing me doubtfully, there were little and big ones, the bearded man and the childish boy, the women-

Some talked easily about their work; most did not. Two large girls stumbled badly in English; their whispers to each other were in rapid, easy Portuguese. The most vocal student was a stringy, slouched boy wearing a black T-

218

In one corner, leaning against the wall, the tablet of her desk teetering, was a slight white girl, apart from the rest of the group but attending with care. She wore studiously unkempt clothes, jeans well ripped at the knees. She took her time to talk, but when she did her language was standard English, her references from a different part of town. Her language separated her even more than her race, but the others ignored her. She seemed oblivious of her isolation. By contrast, the group’s central figure was an older-

5 My impressions of these kids and my conversation with them immediately evoked stereotypes. I guessed from their appearances alone who they were. I knew that this mental sorting-

After a time, the students set to work on their essays, I traveled among them, peering over shoulders, reading the starts of their work. Different people — different stereotypes —emerged. Some could barely write simple prose but could whisper to me rich ideas they were struggling to put to paper. Others, like the isolated white girl, could write easily but could not tell me clearly what they wanted to express. This student of the kneeless jeans presented a tangle of notions. Whatever her technical writing skills, she lacked a coherent story to tell. She was childish, not so much naïve as living in a world of flat simplicities.

Some had no idea of what a narrative was. Others created tales about their brothers that would have dazzled Steven Spielberg. Some loved writing, seemingly losing themselves in concentration. Chicago Bulls whipped off a pageant of paragraphs, his bon mots1 of the earlier discussion now finding their way to paper. His work was sloppy but wonderful. Others slouched, pencils relentlessly tapping, gazing around, a few words put down, not even a sentence, utterly unengaged. Only the Caribbean-

As their attention waned, I shifted the activity to a discussion of a historical incident that once raised and still raises some enduring issues of fundamental justice. As I go among schools, I like to use this particular exercise, because it gives consistency to my class watching. The merchant vessel Emily, out of Salem, Massachusetts, in 1819, dropped anchor in the harbor of Canton, China, to sell and buy goods. While the captain carried out the major transactions, several Chinese entrepreneurs tied their junks up to the ship and noisily hawked their wares to the men on board. One of the seamen, named Terranova, was swabbing the deck near the tethered boat of an especially persistent woman peddler. Somehow a large pottery jug on deck was loosened and fell onto the hawker’s junk. The peddler fell overboard and drowned. The Cantonese authorities demanded that the captain turn Terranova over for trial by a Chinese magistrate. The justice of Canton harbor was balanced, the captain knew, on different scales from those of Massachusetts. The question to the students: If you were the captain, would you turn Terranova over?

219

The case can elicit all sorts of responses: fact gathering, weighing of alternatives, separation of the immediate situation from principle, empathy for a different cultural position, the need to understand trade, Salem, and Canton in the first part of the nineteenth century. And more. The kids jumped in, at first tentatively, then more vociferously. I served as a human encyclopedia, a fact giver; I expressed no opinion. The Cape Verdean girls took positions of principle; Chicago Bulls looked for a quick way out. Just pull anchor and sail away, he argued. Others protested. What about the Emily’s trade next year? What about the rights of the family of the drowned woman? And more. Some refused to make a decision, paralyzed. Again, patterns of response were different; now different stereotypes emerged. The quick portraits I had twice formed disappeared again. Eagle Scout, for example, was silent. He could not make a decision. What might be right for him was not only unclear but unfathomable. I was unfair to push for a decision. He and a few others angrily resented my final call for each student to put on a slip of paper his or her “answer” to the authorities about Terranova’s release to Cantonese law.

10 The complexity of young people was displayed in a ninety-

How can teachers know the students, know them well enough to understand how their minds work, know where they come from, what pressures buffet them, what they are and are not disposed to do? A teacher cannot stimulate a child to learn without knowing that child’s mind any more than a physician can guide an ill patient to health without knowing that patient’s physical condition. Tendencies, patterns, likelihoods exist, but the course of action necessary for an individual requires an understanding of the particulars.

And so, what to do? Remedies are actually obvious. They promise, however, to challenge a clutch of traditional educational practices.

First, the number of students per teacher must be limited. Teachers, even the most experienced, can know well only a finite number of individual students, surely not more than eighty and in many situations probably fewer. The typical secondary school teacher today is assigned anywhere from 100 to over 180, coming at him, rapid fire, in groups of twenty to forty. Horace Smith daily sees five groups of some twenty-

People, adolescents included, are complicated and changeable, and knowing them well is not something one can easily attain or hold on to forever. Kids seem different to different adults; they respond in different ways to different situations or when studying different disciplines. Few students open up to older people they do not know or trust; to know a youngster in order to teach her well means knowing her first as a person. Moreover, there are no perfect tests one can administer to get a permanent fix on a child, no matter how educators struggle to create such devices and to believe in them. Current research on learning and adolescent development is full of speculation, of conflicting findings and incomplete results, and it gives no simple answer to the nature of learning or growing up. In sum, teachers (like parents) are very much on their own, drawing on a mixture of signals from research, from experience, and from common sense as the basis for their decisions.

220

seeing connections

Throughout Horace’s School, Sizer describes a series of Exhibitions, which are long-

An Exhibition: Form 1040

Your group of five classmates is to complete accurately the federal Internal Revenue Service Form 1040 for each of five families. Each member of your group will prepare the 1040 for one of the families. You may work in concert, helping one another. “Your” particular family’s form must be completed by you personally, however.

Attached are complete financial records for the family assigned to you, including the return filed by that family last year. In addition, you will find a blank copy of the current 1040, including related schedules, and explanatory material provided by the Internal Revenue Service.

You will have a month to complete this work. Your result will be “audited” by an outside expert and one of your classmates after you turn it in. You will have to explain the financial situation of “your” family and to defend the 1040 return for it which you have presented.

Each of you will serve as a “co-

Good luck. Getting your tax amount wrong—

221

Here is another educational target.

It is authentic, painfully so. The importance of the 1040 is self-

It will appeal to students. It deals with two issues paramount in most of their lives: money and fairness (the latter particularly if the families selected come from radically different walks of life).

Taught intelligently, it opens the door wide, and for many students in a compelling way, to a cluster of important disciplines such as microeconomics, politics, ethics, and political history. It can thereby be the springboard for sustained serious study in several directions. For example, it raises provocative questions about equality, about what “tax breaks” are and who gets them and why. It is an example of government at work, with its use of financial incentives. In all these respects, it spurs teaching, animates it—

It teaches the importance of accurate, consistent records, the necessity to read closely, the nature of the tax system, and who and what it favors. It also calls for a demonstration of arithmetic, logical, and analytic skills.

It is organized so that students can work together, helping one another. Some may promptly race out and consult a tax expert or call the IRS, asking for help. While this is not recommended, it is tolerable: the costs of such outside help are minimized by the necessity to withstand and explain an audit. Indeed, the act of getting such help may serve as a powerful teacher. Further, the necessity to be another person’s co-

It allows a teacher to vary the difficulty of material among the students involved, giving a financially simpler family to a struggling student and a more complex set of issues to the class tax whiz. The students will, of course, help one another, and they all must stand behind all five returns.

15 Accordingly, and reflecting the ambiguous nature of each student’s progress or lack thereof, wise teachers, knowing that they must be diagnosticians of the youngster’s progress, take counsel regularly with their colleagues about the student, sharing impressions, hunches, and suggestions. Teachers confer with parents. And teachers make time to confer with the student himself, privately — formally or more likely informally — not only in the rush of class time. [. . .]

All this personalization can be taken too far, or worse yet can be bureaucratized with solemn Meetings called on a Schedule to examine Each Student’s Brain and Navel. Compromises and common sense and flexibility are always needed in schools, just as they are in good families. Adjustments must be made quickly and thoughtfully. The key ingredients here are time during the school day for people to meet, schedules that allow the teachers of particular youngsters to gather together, teachers committed to such gatherings, and a school program flexible enough to respond to adjustments recommended for each student. Schools should do no less for students than effective hospitals do for patients. Good hospitals allow time for staff consultations. They expect collaboration in the diagnosis of problems and the selection of remedies. Good hospitals consult patients carefully. Schools are not hospitals and school kids are not “sick,” yet the analogies in this case hold.

Finally, the mores of the school — the ways it goes about its business — must implicitly show respect for individual students, for the expectation that each can succeed, and for the belief that each deserves success. It is in this context that schools’ “dirty little secrets,” incendiary issues like race, can be addressed. A school faculty that knows its students has taken each beyond his or her race, has accepted each as a person. This is not to say that race or gender or ethnicity is not of consequence; it means only that other matters, such as a kid’s personality, his hopes, his friends, his passions, his family, his idiosyncrasies, count more. It is one thing to say, “Those three black kids and those two white kids over there are . . .”; it is better to say, “Bill, Amanda, Susan, Roger, and Ernest . . .” The person emerging from the caricature can help to dissolve the stereotype. A stereotype is one of the roots of prejudice, one readily confronted in good schools. The “dirty little secrets” will never be eliminated or go away: America’s prejudices run too deep for that. The tensions and wranglings they incite will always be with us, and schools must accept them — but always in the context of the reality that no two people, young or old, are ever quite alike, nor should they ever be treated precisely alike.

222

A thoughtful school “culture” cannot be readily codified or structured. An advisory period merely offers the possibility of “advice” given and taken. What happens within that opportunity is the nub of it. Fuzzy but fundamental qualities of caring and honesty, attentiveness both to the immediate and to a young person’s future, empathy, patience, knowing when to draw the line, the expression of disappointment or anger or forgiveness when such is deserved — indeed, those qualities which characterize us as humans rather than programmed robots — mark the essence of a school that is at once compassionate, respectful, and efficient.

How do such schools come to be? Through the leadership of their adults, people who set and reset the standards, people who stay around a school long enough to give it a heart as well as a program, people who are ready to build a community that extends beyond any one classroom, people who know the potentials and limitations of technical expertise and of humane judgment. One does not “design” such schools.

20 Such schools, rather, grow, usually slowly and almost always painfully, as tough issues are met.

Horace’s committee seemed stumped about how to respect the differences among students and yet meet the need for some absolute academic standards. Comparisons to athletics were tried, but what kept cropping up was tracking — with academic varsities, junior varsities, and the rest.

The problem, committee members knew, was that the game of life was all played at the varsity level. In the use of their minds, if not their passing arms and kicking feet, all the young people had to be made as competitive as possible.

“Take your taxes,” Margaret suggested. “Everybody has to do his taxes. Taxophobes are not let off. Everyone must be able to play that game.”

There was laughter. “The Form 1040 is the test we all must pass . . .” More embarrassed laughter.

25 “Not everyone will be able to make sense of all that IRS gobbledygook.”

“Why not?” Margaret persisted. “It isn’t all that hard. It takes time, persistence, careful reading, good records, patience galore. Why can’t we set those ends as a standard for any Franklin graduate?”

“In the real world, lots of people do their taxes with others. In our house it’s a collective late March hassle. And if we don’t understand, we ask for help.”

“So, isn’t that OK?” Margaret again. “We can’t teach every student the tax code forever and ever, but we should be able to expect every

“Can we expect the same of the faculty?” More laughter. The committee was learning to like itself.

30 Green: “The 1040 is the Real World. Why isn’t that a good Exhibition?”

Again someone protested: “It will be too hard for some of the kids!”

Coach: “It can’t be. They have to be able to do it.”

223

Understanding and Interpreting

At the beginning of this selection, Theodore Sizer describes several of his students in simplistic, stereotypical terms, but by paragraph 10, he concludes, “Beautifully complicated these students were.” What changes for Sizer, and what is the reader expected to conclude from his changed perceptions?

What is Sizer’s intention in asking the students about the story of the merchant ship Emily? What is he hoping to learn? What conclusion is the reader expected to draw from the inclusion of the students’ responses?

Sizer concludes, probably unsurprisingly, that in order to personalize instruction, teachers have to know their students. In addition to large class sizes, to what other factors does Sizer attribute the difficulty of teachers’ knowing their students well?

Sizer compares an effective school to an effective hospital. While he identifies the effective practices that occur in a hospital, he does not explicitly identify how these practices would look in a school. Finish the comparison for Sizer by explaining what the effective school practices might be.

Sizer suggests that the most important step a school can take to ensure that all students are receiving individualized attention is to look closely at “the mores of the school” (par. 17). According to Sizer, what is an effective school culture?

In the last section of this excerpt (pars. 21–

32), Sizer switches to the “nonfiction fiction” approach and describes the fictional faculty meeting that Horace leads. How does the teachers’ dialogue illustrate the points that Sizer makes in the preceding paragraphs?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

This excerpt is taken from a chapter called “Kids Differ.” In what ways does Sizer illustrate the meaning of the chapter title through his word choice in the first four paragraphs, where he describes the kids in the class he is teaching?

Select one of the students whom Sizer observes while teaching the class at the beginning of the excerpt. How does Sizer describe that student upon first encountering him or her, and how do his descriptions change later on? How does this changing language illustrate a point that Sizer is making about the individual in school?

Ultimately, this piece is an argument, making a point about the need for individualized knowledge of students. Why does Sizer start with a narrative? How does the story he tells support his argument?

After the narrative opening about the classroom he visited, Sizer switches to an expository mode of address. Does his attitude toward his topic shift or remain the same? Point to specific language choices in each part of the selection to support your conclusion.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Sizer spends considerable time identifying the qualities of an effective school culture. Compare your own school’s culture to the ideal one that Sizer describes.

Reread the scenario of the merchant ship Emily (par. 8). What is your opinion on the case? What might your response reveal about you?