388

from Animal Farm

George Orwell

George Orwell (1903–

KEY CONTEXT Written at the end of World War II, Animal Farm (1945) is an anti-

Comrades, you have heard already about the strange dream that I had last night. But I will come to the dream later. I have something else to say first. I do not think, comrades, that I shall be with you for many months longer, and before I die, I feel it my duty to pass on to you such wisdom as I have acquired. I have had a long life, I have had much time for thought as I lay alone in my stall, and I think I may say that I understand the nature of life on this earth as well as any animal now living. It is about this that I wish to speak to you.

“Now, comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short. We are born, we are given just so much food as will keep the breath in our bodies, and those of us who are capable of it are forced to work to the last atom of our strength; and the very instant that our usefulness has come to an end we are slaughtered with hideous cruelty. No animal in England knows the meaning of happiness or leisure after he is a year old. No animal in England is free. The life of an animal is misery and slavery: that is the plain truth.

“But is this simply part of the order of nature? Is it because this land of ours is so poor that it cannot afford a decent life to those who dwell upon it? No, comrades, a thousand times no! The soil of England is fertile, its climate is good, it is capable of affording food in abundance to an enormously greater number of animals than now inhabit it. This single farm of ours would support a dozen horses, twenty cows, hundreds of sheep — and all of them living in a comfort and a dignity that are now almost beyond our imagining. Why then do we continue in this miserable condition? Because nearly the whole of the produce of our labour is stolen from us by human beings. There, comrades, is the answer to all our problems. It is summed up in a single word — Man. Man is the only real enemy we have. Remove Man from the scene, and the root cause of hunger and overwork is abolished for ever.

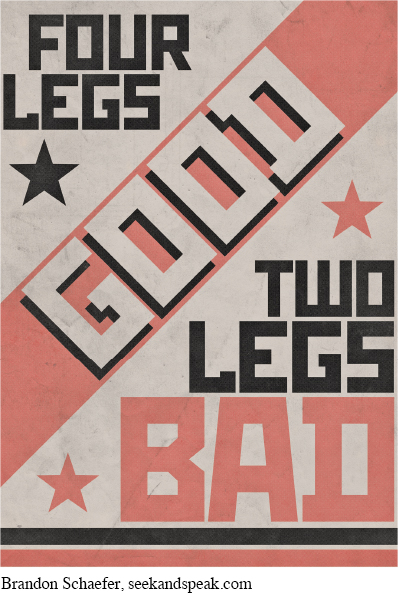

During the time that Orwell wrote this novel, the Soviet Union made effective use of propaganda, including posters with simple slogans and images.

“Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself. Our labour tills the soil, our dung fertilises it, and yet there is not one of us that owns more than his bare skin. You cows that I see before me, how many thousands of gallons of milk have you given during this last year? And what has happened to that milk which should have been breeding up sturdy calves? Every drop of it has gone down the throats of our enemies. And you hens, how many eggs have you laid in this last year, and how many of those eggs ever hatched into chickens? The rest have all gone to market to bring in money for Jones and his men. And you, Clover, where are those four foals you bore, who should have been the support and pleasure of your old age? Each was sold at a year old — you will never see one of them again. In return for your four confinements and all your labour in the fields, what have you ever had except your bare rations and a stall?

389

5 “And even the miserable lives we lead are not allowed to reach their natural span. For myself I do not grumble, for I am one of the lucky ones. I am twelve years old and have had over four hundred children. Such is the natural life of a pig. But no animal escapes the cruel knife in the end. You young porkers who are sitting in front of me, every one of you will scream your lives out at the block within a year. To that horror we all must come — cows, pigs, hens, sheep, everyone. Even the horses and the dogs have no better fate. You, Boxer, the very day that those great muscles of yours lose their power, Jones will sell you to the knacker, who will cut your throat and boil you down for the foxhounds. As for the dogs, when they grow old and toothless, Jones ties a brick round their necks and drowns them in the nearest pond.

“Is it not crystal clear, then, comrades, that all the evils of this life of ours spring from the tyranny of human beings? Only get rid of Man, and the produce of our labour would be our own. Almost overnight we could become rich and free. What then must we do? Why, work night and day, body and soul, for the overthrow of the human race! That is my message to you, comrades: Rebellion! I do not know when that Rebellion will come, it might be in a week or in a hundred years, but I know, as surely as I see this straw beneath my feet, that sooner or later justice will be done. Fix your eyes on that, comrades, throughout the short remainder of your lives! And above all, pass on this message of mine to those who come after you, so that future generations shall carry on the struggle until it is victorious.

390

“And remember, comrades, your resolution must never falter. No argument must lead you astray. Never listen when they tell you that Man and the animals have a common interest, that the prosperity of the one is the prosperity of the others. It is all lies. Man serves the interests of no creature except himself. And among us animals let there be perfect unity, perfect comradeship in the struggle. All men are enemies. All animals are comrades.”

At this moment there was a tremendous uproar. While Major was speaking four large rats had crept out of their holes and were sitting on their hindquarters, listening to him. The dogs had suddenly caught sight of them, and it was only by a swift dash for their holes that the rats saved their lives. Major raised his trotter for silence.

“Comrades,” he said, “here is a point that must be settled. The wild creatures, such as rats and rabbits — are they our friends or our enemies? Let us put it to the vote. I propose this question to the meeting: Are rats comrades?”

10 The vote was taken at once, and it was agreed by an overwhelming majority that rats were comrades. There were only four dissentients, the three dogs and the cat, who was afterwards discovered to have voted on both sides. Major continued:

“I have little more to say. I merely repeat, remember always your duty of enmity towards Man and all his ways. Whatever goes upon two legs is an enemy. Whatever goes upon four legs, or has wings, is a friend. And remember also that in fighting against Man, we must not come to resemble him. Even when you have conquered him, do not adopt his vices. No animal must ever live in a house, or sleep in a bed, or wear clothes, or drink alcohol, or smoke tobacco, or touch money, or engage in trade. All the habits of Man are evil. And, above all, no animal must ever tyrannise over his own kind. Weak or strong, clever or simple, we are all brothers. No animal must ever kill any other animal. All animals are equal.”

Understanding and Interpreting

According to Old Major, what is the fate of every animal and why is it unjust?

Old Major acknowledges that a rebellion may not happen for one hundred years, long after the lives of the animals he is speaking to have ended (par. 6). What does he suggest that the animals do in order to overcome this obstacle and keep the hope of rebellion alive?

Why does the cat vote on both sides of the issue regarding whether or not wild creatures are comrades?

Old Major makes a distinction between the farm animals and the “wild creatures” such as rats and rabbits, and then calls for a vote to determine if these wild creatures are comrades (pars. 9–

10). What is Old Major’s purpose in asking the farm animals to take this vote? What are the “habits of Man” (par. 11), according to Old Major, and why does he admonish the animals to never take on these habits themselves?

391

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

In the second paragraph, how do the adjectives serve to establish the “plain truth” about the life of animals for Old Major’s argument?

What function does Old Major’s rhetorical question in the second paragraph serve in the structure of his overall argument?

What evidence does Old Major use to support his ultimate claim that Man is “the only real enemy” (par. 3) that the animals have?

What rhetorical strategies does Old Major rely on in presenting his argument? Do you find them effective?

How does Old Major’s assertion “All men are enemies. All animals are comrades” (par. 7) effectively promote his call for rebellion?

Old Major concludes his call for rebellion with the statement that “[a]ll animals are equal.” How does this declaration ultimately support his purpose?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Orwell’s Animal Farm is an allegory. In Old Major’s speech, the farm animals represent the workers, and the humans represent the capitalists who profit from their labor. What might Animal Farm be an allegory for in contemporary times? What would Old Major rebel against today?

There are many movements that fight for animal rights, specifically farm animal rights. Research some organizations working for this cause, and compare the rhetoric in their messaging. Do they echo Old Major’s speech in any way?

The novel Animal Farm was written in the 1940s, a time when there were fears about the rise of communism in general, and the Soviet Union and Stalin in particular. Was Animal Farm effective as anti-

communist literature? Read the novel yourself, then research how the story is read and taught in schools, and research what its cultural legacy seems to be. Based on that, determine if it was ultimately effective at its rhetorical purpose.