7.20

510

from The Cheating Culture: Why More Americans Are Doing Wrong to Get Ahead

David Callahan

David Callahan (b. 1965) is a cofounder of the liberal-

KEY CONTEXT At the beginning of this excerpt, Callahan refers to what he calls “the Winning Class,” which he describes as those people in society who are successful economically, but who utilize unethical means to get there. Later in the excerpt Callahan refers to the “social contract,” which is a political theory that people in a society willingly submit some of their individual freedoms to a government they perceive as legitimate in return for basic protections and services. One example of a social contract is that when people pay taxes, they have a reasonable expectation that public schools will provide education for their children.

For those who are part of the Winning Class, or trying to be, there are plenty of reasons to cheat. The rewards are bigger and the rules are toothless. Yet many Americans with more modest ambitions and more humble means are also cheating.

Take the mild-

The bookkeeper works hard during the early years of his job and finally gets up the gumption to ask for a raise of $100 a month. He is crushed when the request is denied. But the bookkeeper seems to get over his disappointment and soldiers on. He still arrives punctually every day. He never calls in sick when, in truth, he is well.

After twenty years, the bookkeeper finally retires. The company throws a small farewell party for him and gives him a watch. He and his wife pack up for Florida to start their golden years. A new bookkeeper takes his place. Poring over the financial records, this new bookkeeper finds that something is wrong. Things aren’t adding up. He flags his concern to the company. No, no, he’s told, the old bookkeeper would never get into any fishy business. He was a rock of reliability, the soul of integrity.

5 And yet, when the new bookkeeper completes his investigation, the facts are in

511

The thieving bookkeeper exists in an apocryphal story passed down over many years among fraud examiners who probe workplace theft. The story is told to illustrate a point these investigators know all too well: that people are prone to invent their own morality when the rules don’t seem fair to them. This tendency explains a lot of cheating in America today.

There are roughly four reasons why people obey rules. First, we may toe the line because the risks of breaking the rules outweigh the benefits. Second, we might be sensitive to social norms, or peer pressure — we follow the rules because we don’t want to be treated as a pariah. Third, we may obey rules because they agree with our personal morality. And fourth, we may obey rules because they have legitimacy in our eyes — because we feel that the authority making and enforcing the laws is just and ultimately working in our long-

When people don’t obey the rules, you’ll often find several things going on at once. The Winning Class cheats so much because there’s more to be gained nowadays and there are fewer penalties, either legally or socially. Students often cheat for the same reasons: the stakes of academic competition are higher and the normalization of cheating means that there’s little peer pressure to be honest.

Motives like these are not hard to understand. Cases like the bookkeeper are more complex. A simple risk/benefit analysis doesn’t explain everything, since the bookkeeper was running a serious risk for only a modest sum of money and could easily have taken more. Nor do social norms offer much insight, since the bookkeeper’s thefts were not condoned by his peers. Instead, the bookkeeper operated by his own moral code to take from the company what he felt it owed him.

10 A lot of Americans have been inventing their own morality lately. Tens of millions of ordinary middle-

Day-

What is going on here?

Much of the answer, I suspect, lies in our broken social contract. An orderly democratic society depends on having a social contract in place that delineates people’s rights and responsibilities. It also depends on people having faith that the social contract applies fairly across the board. The social contract will break down when those who play by the rules feel mistreated, and those who break the rules get rewarded — which has been happening constantly in recent years.

John Q. Public need not to be versed in John Locke to feel that he has a legitimate cause for cynicism. He knows that white-

512

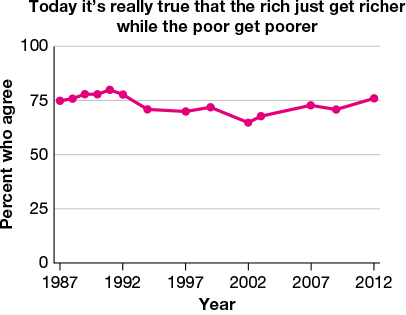

15 Polls confirm that many Americans see “the system” as rigged against them. When asked who runs the country, many say corporations and special interests. When asked who benefits from the tax system, most say the rich. When asked who is underpaid in our society, most agree that lots of people are underpaid: nurses, policemen, schoolteachers, factory workers, restaurant workers, secretaries. And when people are asked whether it is possible to get ahead just by working hard and playing by the rules, many say that it is not.2 [. . .]

The psychological fallout from people’s economic struggles has been significant. People worry intensely about their finances, especially the heavy debt burdens that they often carry.3 Many people are also less happy. “Happiness and satisfaction with life are, in many ways, the ultimate bottom line, a test of the good society,” observes scholar Michael Hout. Yet in the past quarter century, Hout’s work shows, gains in happiness have not been shared evenly in a U.S. society more divided by income: “the affluent are getting slightly happier and the poor are getting sadder; the affluent are increasingly satisfied with their financial and work situation while the poor are increasingly dissatisfied with theirs.”4

Such endemic unease might itself be a corrupting force in society. But economic struggle is all the more dangerous when mixed with high expectations of well-

Merton could have made these points yesterday. The pressures on Americans to make a lot of money are extremely high —higher, maybe, than they’ve ever been before. To be sure, there are many legitimate opportunities to do well financially. Yet ultimately the opportunities are finite. America needs only so many skilled and well-

What to do in this conundrum? Whatever you can get away with.

20 And how do ordinary, moral people justify doing wrong to do well? Often, they point to the unfairness around them — to the structures that keep them struggling while others thrive, to the ways that bad guys easily climb to the top, to the cheating that goes on by the rich and powerful every day. “People in subordinate positions make moral judgments about existing social arrangements and assert their prerogatives to personal entitlements and autonomy,” writes Elliot Turiel, a leading authority on moral development. Turiel is fascinated with why people break rules, and much of his analysis centers on what he dryly calls “asymmetrical reciprocity implicit in differential distribution of power and powers” — in other words, feelings of injustice. Turiel observes that “in daily life people engage in covert acts of subterfuge and subversion aimed at circumventing norms and practices judged unfair, oppressive, or too restrictive of personal choices.” These acts may place people on the wrong side of the law, or the established rules, Turiel says, but their true ethical implications are often a fuzzier question. “In my view, it would be inaccurate to attribute these types of acts of deception to failures of character or morality. Many who engage in these acts are people who generally consider themselves and are considered by others as responsible, trustworthy, upstanding members of our culture.”6

513

Identify a sentence from the Callahan piece that would support the point being made by the artist in this cartoon.

It is easy to cheat like crazy and yet maintain respect for yourself in a society with pervasive corruption. It’s easy, for example, to justify cheating in a country like Brazil where oligarchical families have been abusing the little people for a couple of hundred years and are still doing it, or a country like Pakistan where government ministers and their pals in business live in luxury while millions rot in the slums of Karachi.

And more and more, similar rationalizations can work just fine in the United States.

The social theorist Max Weber was among the first scholars to explore how people’s views of “legitimacy” shape their respect for rules. He argued the commonsense point that people are more likely to follow rules or laws that seem fair and are made by an authority that deserves its power. There was nothing actually path-

514

seeing connections

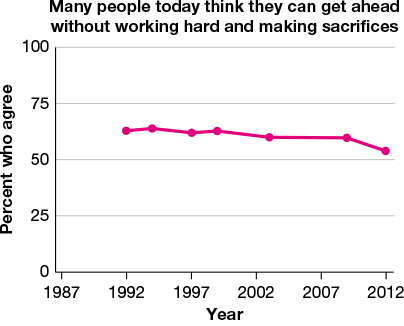

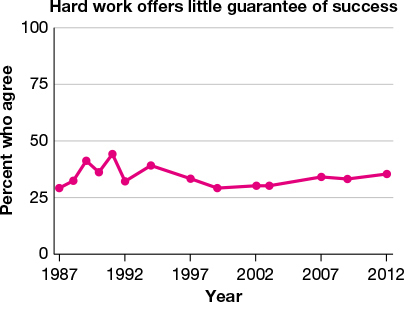

The following charts present data from the Pew Research Center American Values Survey, which tracks changes in American values over time.

State a claim that Callahan makes about a reason that Americans are willing to cheat and support that statement with a conclusion that you draw from one of these charts.

Proof that views about legitimacy explain ethical decisions remains hard to come by. But the evidence has gotten a lot more compelling since Weber’s day. In his 1990 book, Why People Obey the Law, Tom Tyler picked up the legitimacy baton and ran with it into new empirical terrain. Tyler marshaled data going back thirty five years in arguing that most people are inclined to obey the law, but that this reflex can easily be undermined if the law is widely seen as lacking legitimacy. He looked at studies of juvenile delinquents in England, college students in Kentucky, middle-

515

25 Yet if the link between respecting authority and following the rules has found more support in general, this is still complex terrain. Much of the time when people break rules you’ll find a sticky wicket of conflicting evidence about their motives and no easy way to nail down what they were really thinking. Most people don’t like to talk openly about cutting corners. Also, the root causes of why people break rules can be obscured when cheating becomes so routine that people no longer give it much thought.8

The candor of Jennifer Bennett (not her real name) sheds some light on what is going on in many American households — and, in particular, how cynicism and anger might cause a person who normally wouldn’t even run a red light to commit a felony that is punishable by up to five years in prison.

Bennett should be one of the good guys in my story. She was raised in New Jersey by parents who taught her to play by the rules. She works in the arts in New York City but is obsessed with neither money nor status. She just wants to do her art and get by. She believes that government can make a difference in people’s lives and, if anything, that taxes should probably be higher than they are.

Yet every year, come April 15, she submits a work of fiction to the IRS.

“Much of the money I earn is off the books — it’s money earned in cash through private teaching or tutoring. I generally claim a portion of this money, but not all of it,” Bennett says. “It’s the money I earn to support my pursuit of a career in the arts. I put thousands of dollars a year into this career, pay my own insurance, and receive no benefits. I guess that’s the way I justify writing off as much as I can and claiming as little as I can. I feel that most other first-

30 Bennett has struggled financially for years, despite her Ivy League degree. Meeting the rent has often been an adventure, and she now lives 130 blocks north of Times Square, in a low-

Bennett has anguished about her tax cheating — for, like, three seconds — over the past five years. “I don’t think it’s the ‘right’ thing to do, but personally, I don’t really care. I know that one wrong doesn’t right another wrong, but until I see any sign of a real move to universal health-

516

Understanding and Interpreting

Several times in the piece, Callahan describes people “inventing their own morality” (for example, par. 10). What does he mean by this phrase?

Callahan claims that a lot of the cheating by ordinary, otherwise law-

abiding citizens is due to “our broken social contract” (par. 13). Reread paragraphs 13– 18, where he supports this claim. What evidence does he use and to what extent does he sufficiently support his claim? Do you detect any bias that might prevent him from seeing other possibilities? Explain. In paragraphs 16 and 17, Callahan connects the idea of cheating with the desire for happiness. What is the conclusion that he expects the reader to draw about the “high expectations of well-

being” from the evidence he provides? Evaluate his logical reasoning in this section. To support his argument, Callahan cites Elliot Turiel, “a leading authority on moral development.” Reread the following quotes from Turiel, summarize them, and explain how they relate to Callahan’s central argument:

“[P]eople in subordinate positions make moral judgments about existing social arrangements and assert their prerogatives to personal entitlements and autonomy” (par. 20).

“asymmetrical reciprocity implicit in differential distribution of power and powers” (par. 20).

“[I]n daily life people engage in covert acts of subterfuge and subversion aimed at circumventing norms and practices judged unfair, oppressive, or too restrictive of personal choices” (par. 20).

517

Callahan claims that at least one reason why otherwise honest people cheat is the way they view the legitimacy of power. Summarize his views on legitimacy and explain how he uses evidence to support his position.

In paragraph 7, Callahan identifies four reasons why people obey rules. Apply these four reasons to the case of the artist Jennifer Bennett, who regularly cheats on her taxes (pars. 26–

31). Which ones would Bennett likely agree or disagree with? Why?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What role does the fictional story of the bookkeeper play in setting up Callahan’s argument? In other words, why begin this section with the story?

Trace the development of Callahan’s argument from the beginning to the point where he asks: “And how do ordinary, moral people justify doing wrong to do well?” (par. 20). What components does Callahan have to include in his argument before he can ask this question?

It is no secret that Callahan is politically liberal and often sees middle-

and working- class people as victims of the rich. Look back through the article and identify places where he chooses words with negative connotations to describe the wealthy. Does this word choice seem to be effective in making his argument, or is it detrimental? Why? Reread the paragraph that concludes with note 8. The last sentence makes a claim about people’s behavior that appears to be unsubstantiated. Read note 8 and explain how Callahan uses the sources to support his claim. Choose one other annotation from the article and explain how the use of evidence affects Callahan’s ethos.

Until paragraph 21, Callahan focuses on cheating in the United States, at which point he expands his argument to include Brazil and Pakistan. What is the purpose of this switch? How does it assist his argument?

While much of Callahan’s argument is rooted in logos, he does at times employ appeals to pathos. Identify these places and evaluate their effectiveness in supporting his claim.

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

In this selection from The Cheating Culture, Callahan mostly focuses on identifying the causes of cheating. Later on in the book, he offers some solutions, which include a need to teach the values he thinks are important: “respect, responsibility, fairness, honesty, justice.” Where and how are these values best taught? Home, school, religious institutions, other organizations? Why?

In an article from the Springfield State Journal-

Register in 2008, “A recent survey conducted by the University of Hertfordshire showed that the average teen has 800 illegally obtained songs on his or her MP3 or other music- playing device. This same survey showed that 50 percent of people between 14 and 24 would share all of their music on their computers.” Write an argumentative piece in which you take a position on the issue of illegal downloading of music and/or movies. Is this cheating? Why or why not? Be sure to refer to Callahan as evidence to support your claims or as part of your counterclaims. How does the phrase “Everybody does it” apply to cheating in your own life and experiences? Is it difficult to be the one who does not, or is the idea itself that “everybody does it” overblown by adults and the media? What would Callahan’s response likely be?