8.7

The St. Crispin’s Day Speech

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (1564–

KEY CONTEXT The excerpt that follows is from the historical play Henry V, which is about the war between England and France in the 1400s. This scene from the play takes place just before the Battle of Agincourt, in which the advancing English army is about to face the French forces that greatly outnumber them. Hearing about their disadvantage, one of the English lords says that he wishes that they had “But one ten thousand of those men in England / That do no work to-

569

Despite their overwhelming disadvantage in numbers, the British were victorious at Agincourt. While Shakespeare might attribute the success to Henry’s inspirational speech before the battle, history tells us that his army had mastered the use of the English longbow, a relatively new weapon at the time.

The English camp.

Enter Gloucester, Bedford, Exeter, Erpingham, with all his host: Salisbury and Westmoreland

GLOUCESTER Where is the king?

BEDFORD The king himself is rode to view their battle.

WESTMORELAND Of fighting men they have full three score thousand.

EXETER There’s five to one; besides, they all are fresh.

5 SALISBURY God’s arm strike with us! ’tis a fearful odds.

God be wi’ you, princes all; I’ll to my charge:

If we no more meet till we meet in heaven,

Then, joyfully, my noble Lord of Bedford,

My dear Lord Gloucester, and my good Lord Exeter,

10 And my kind kinsman, warriors all, adieu!

BEDFORD Farewell, good Salisbury; and good luck go with thee!

EXETER Farewell, kind lord; fight valiantly to-

And yet I do thee wrong to mind thee of it,

For thou art framed of the firm truth of valour.

Exit Salisbury

15 BEDFORD He is full of valour as of kindness;

Princely in both.

Enter the King

WESTMORELAND O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work to-

20 KING HENRY V What’s he that wishes so?

My cousin Westmoreland? No, my fair cousin:

If we are mark’d to die, we are enow

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

25 God’s will! I pray thee, wish not one man more.

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

It yearns me not if men my garments wear;

Such outward things dwell not in my desires:

30 But if it be a sin to covet honour,

I am the most offending soul alive.

No, faith, my coz, wish not a man from England:

God’s peace! I would not lose so great an honour

As one man more, methinks, would share from me

35 For the best hope I have. O, do not wish one more!

Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made

And crowns for convoy put into his purse:

40 We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is called the feast of Crispian:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-

45 And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say “To-

570

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

50 And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day: then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words

55 Harry the king, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

Be in their flowing cups freshly remember’d.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

60 From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

65 This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.

seeing connections

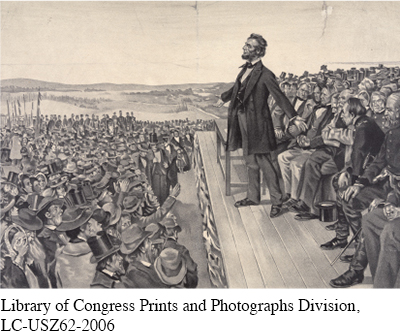

Read the last paragraph of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, considered by many to be among the best speeches ever delivered. Lincoln gave his speech to dedicate a memorial for the soldiers who died at Gettysburg in 1863, at a time when the United States was still in the middle of the Civil War. He knew his speech would be widely reported, and his audience included those on both sides of the conflict.

Compare Lincoln’s arguments about why the war ought to continue with Henry’s arguments in “The Saint Crispin’s Day Speech.”

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate—

571

Understanding and Interpreting

In the lines before Henry starts his speech, we hear from some of his noblemen. What fears do they express and to what extent is Henry able to alleviate their fears in his speech?

Rewrite the following lines into your own words and explain what Henry is saying:

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

It yearns me not if men my garments wear;

Such outward things dwell not in my desires:

But if it be a sin to covet honour,

I am the most offending soul alive.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say “To-

morrow is Saint Crispian:” Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say “These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.”

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember’d;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-

day that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile.

One of the major arguments Henry puts forward to convince his men to fight is seen in the line, “and if to live, / The fewer men, the greater share of honour” (ll. 23–

24). What conclusion is Henry hoping his men draw from this line? From a practical standpoint, the majority of Henry’s army would have consisted not of noblemen like himself, but poor peasants who likely would never have even seen Henry before if it weren’t for this war. What did Henry include in his speech to appeal to this aspect of his audience?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Reread lines 26–

29. How does Henry establish his ethos with his audience? How does the idea Henry presents in lines 30–

31 contrast with lines 26– 29? What is the purpose of this contrast? What does Henry propose to his men in lines 36–

41? Why is this an effective rhetorical strategy for Henry to use in this context? After line 41, there is a shift in topic from dying in battle to living through the battle. What is the importance of this shift at just about the halfway point in the speech?

In lines 55–

56, Henry includes a series of names. What purpose does the inclusion of these names serve? Reread lines 61–

62. The word “we” is repeated four times and rhymed with “me” in line 63. What is the effect of this repetition and the rhyming?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Locate advertisements for the United States military online, in magazines, or in other sources. In what ways are their appeals similar to or different from the claims that Henry makes in this speech?

What is an argument that could be used against Henry? Why should the mostly peasant army not fight on behalf of the royal family? Write a response that someone in Henry’s audience who opposes Henry’s argument might have made. If you want, you can choose to write the response in poetic form to match Shakespeare’s style.

Imagine that you are a newspaper reporter who has just witnessed Henry’s speech. Write a headline and article about it. Be sure to include an interview with one of Henry’s men.

Shakespeare rarely includes stage directions other than “enter,” “exit,” and “dies.” What are some significant stage directions that you could imagine including? Focus on Henry’s actions, gestures, and interactions with his audience, as well as any movements and responses from his audience.