9.12

Slang for the Ages

Kory Stamper

Kory Stamper is a lexicographer and editor for the Merriam-

Everyone knows that slang is informal speech, usually invented by reckless young people, who are ruining proper English. These obnoxious upstart words are vapid and worthless, say the guardians of good usage, and lexicographers like me should be preserving language that has a lineage, well-

In fact, much of today’s slang has older and more venerable roots than most people realize.

Take “swag.” As a noun (“Check out my swag, yo / I walk like a ballplayer” — Jay Z), a verb (“I smash this verse / and I swag and surf” — Lil Wayne), an adjective (“I got ya slippin’ on my swag juice” — Eminem), and even as an interjection (“Say hello to falsetto in three, two, swag” — Justin Bieber), swag refers to a sense of confidence and style. It’s slangy enough that few dictionaries have entered it yet.

774

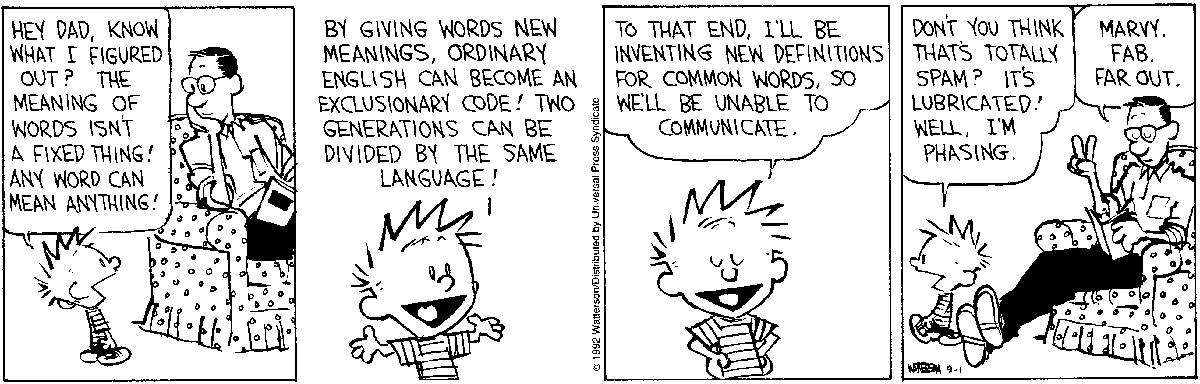

Where’s the joke in this cartoon? Is the artist being entirely facetious in this depiction of an exchange between father and son, or does he have a serious point? Do you think “ordinary English” can become “an exclusionary code”? When does healthy change become “exclusionary”?

Swag sounds new, but the informal use goes way back. It’s generally taken to be a shortened form of the verb “swagger,” which was used to denote a certain insolent cockiness by William Shakespeare, O.G. The adjectival use dates to 1640, and seems to have a similar connotation to the modern swag (“Hansom swag fellowes and fitt for fowle play” — John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, in The Tragedy of Sir John van Olden Barnavelt). The noun was first used even earlier: One 1589 citation reads like an Elizabethan attempt at freestyle (“lewd swagges, ambicious wretches”).

5 Nor was Mr. Bieber the first to use the word because he liked how it finished a line. The English playwright William Davies wrote, in 1786, of one of his characters that she moved like a half-

The website Gawker prophesied in 2012, and Mr. Bieber averred last year, that swag is over. It takes some swag to call time on a piece of slang that goes back centuries; and, in any case, Google Trends shows that the usage is holding steady. Swag is dead; long live swag.

Swag evolved out of standard English, but there’s also slang that is slang born and raised. As it moves through successive generations, it may morph — but without losing its cred.

“Fubar” was first used in print in 1943; it is an acronym whose expanded version I will bowdlerize as “rhymes with trucked up beyond all recognition.” This was slang created by the Greatest Generation as Americans marched to war, a shining example of how G.I.s adapted the custom of military acronyms to their own purposes.

Fubar had its heyday during the war, then fell out of use. But it never disappeared entirely. Decades later, it was appropriated by another kind of acronym-

10 Was it still slang? Definitely. Restricted to young people? Not so much. Fubar still enjoys slang use among the hip and Internet-

775

seeing connections

In this excerpt, Tom Dalzell, slang expert and author of Flappers 2 Rappers: American Youth Slang, discusses the roots of slang in American English.

The four factors that are the most likely to produce slang are youth, oppression, sports, and vice, which provide an impetus to coin and use slang for different sociolinguistic reasons. Of these four factors, youth is the most powerful stimulus for the creation and distribution of slang. [. . .]

Youth slang derives some of its power from its willingness to borrow from other bodies of slang. Despite its seeming mandate of creativity and originality, slang is blatantly predatory, borrowing without shame from possible sources. Foremost among them is the African-

How does Dalzell’s perspective on slang differ from Kory Stamper’s historical analysis? What new perspective on language and power does Dalzell provide?

Speaking of hip, hipsters have been derided as know-

Slang often falls prey to what linguists call the “recency illusion”: I don’t remember using or hearing this word before, therefore this word is new (often followed by the Groucho Marx sentiment: “Whatever it is, I’m against it”). At the heart of the illusion lies a misbegotten belief that English is a static and uniform language, a mighty mountain of lexical stability. Upon this monument, slang falls like acid rain, eroding and degrading the linguistic landscape.

It’s the wrong metaphor. English is fluid and enduring: not a mountain, but an ocean. A word may drift down through time from one current of English (say, the language of World War II soldiers) to another (the slang of computer programmers). Slang words are quicksilver flashes of cool in the great stream.

Some words disappear, and others endure. One thing is sure: The persistence of slang doesn’t mean that English is Fubar. In fact, it’s swag, bae.

776

Understanding and Interpreting

What is the main point that Kory Stamper makes in this article? Where does she state it as an explicit thesis?

What does the author mean by “the modish vulgarities of street argot” (par. 1)?

How do the two examples, “swag” and “fubar,” relate to and support Stamper’s thesis?

What does Stamper mean by her statement: “Swag evolved out of standard English, but there’s also slang that is slang born and raised” (par. 7)? What distinction is she drawing?

What is the “recency illusion” Stamper considers in paragraph 12?

How would you describe Stamper’s overall attitude toward slang? To what extent does she value the rules and conventions of standard English?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

What is the effect of the opening paragraph? What do you think Stamper’s intention is?

Stamper discusses two main examples (“swag” and “fubar”) and mentions several others. Do all of these examples support the same point, or does Stamper use some of them as evidence for sub-

claims? Explain why you think the way you do, with specific reference to the text. What is the effect of Stamper’s integration of slang expressions into this piece? Does her use of slang undermine her credibility? Why or why not?

Stamper uses a number of metaphors in the second half of her essay. Which one(s) do you find most effective? Why?

This essay was published in the New York Times in 2014. Who is her audience? How does she appeal to them?

How would you describe Stamper’s tone? How does her tone reinforce the point she makes in her essay?

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

Is Stamper right? No doubt you’ve heard many warnings about the importance of avoiding slang, and you may have even heard that slang is dangerously close to clichéd and trite language. Does slang characterize a speaker as creative and dynamic, lazy and dull, or something in between? Explain your position with reasons and examples.

How does slang work to connect members of a group you know well (for instance, sports fans, computer geeks, movie buffs, foodies)? Write an essay analyzing some of the slang expressions that have become part of this specific group’s language.

Research a term that has changed its meaning over time, perhaps one that began as slang and has crossed over into standard English, or perhaps one from standard English whose meaning has changed over time as a slang term.

Create a dialogue between two people who are experiencing difficulty communicating because one is using slang (and colloquial) expressions and the other is using standard English exclusively. Your two speakers might be from different historical eras, different generations, or different groups within the same time period.