9.20

The Hoax of Digital Life

Tim Egan

Currently a regular contributor to the New York Times editorial section, Tim Egan (b. 1954) is a journalist and writer who lives in Seattle, Washington. He has written several nonfiction books about American history, including The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl, published in 2006, and The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, published in 2008.

KEY CONTEXT This article was originally published as an op-

808

Ionce tried to talk somebody out of pursuing a mail-

The case of Manti Te’o, the Notre Dame linebacker and finalist for college football’s highest honor, and his fake dead girlfriend takes this question to a whole new level. How can someone claim to have fallen in love with a woman he never met?

The answer, in part, is what’s wrong with love and courtship for a generation that values digital encounters over the more complicated messiness of real human interaction. As my colleague Alex Williams reported in a widely discussed piece a few days ago, screen time may be more important than face time for many 20-

Technology, with its promise of both faux-

seeing connections

Blogger Alexandra Samuel would likely be frustrated with what she would call the unnecessarily broad distinction that Egan draws between our online and offline lives.

Look at an excerpt from her article titled “10 Reasons to Stop Apologizing for Your Online Life” and explain how she would probably respond to the conclusions that Egan draws in this article. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the four suggestions Samuel has for your own online life?

There’s no denying the differences between life online and off. In our online lives we shake off the limitations of our physical selves, perhaps even our names and consciences, too. What remains are the fundamentals: human beings, human conversations, human communities. To say that “reality” includes only offline beings, offline conversations and offline communities is to say that face-

When you commit to being your real self online, you discover parts of yourself you never dared to share offline.

When you visualize the real person you’re about to email or tweet, you bring human qualities of attention and empathy to your online communications.

When you take the idea of online presence literally, you can experience your online disembodiment as a journey into your mind rather than out of your body.

When you treat your Facebook connections as real friends instead of “friends,” you stop worrying about how many you have and focus on how well you treat them.

5 Before the fraud was revealed, Te’o recalled to the Chicago Tribune one of the final conversations he had with the made-

809

If Notre Dame wasn’t the land of leprechauns, Win-

But let’s take the nation’s most storied Catholic university at its word. And, as explained by Notre Dame officials on Wednesday night, after they’d hired a private investigative firm to sort out the details, the story is a compelling parable of digital dating culture.

At the center of this episode is the astonishing assertion by the Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick that Te’o never actually met his phantom lover. Never. No face time. The entire relationship was electronic. And yet she was likely to become his wife, according to Te’o’s father.

“The issue of who it is, who plays the role, what’s real and what’s not here is a more complex question than I can get into here,” said Swarbrick, at the press conference on Wednesday. Actually, it’s not that complicated. The woman either existed, and then died, or didn’t exist, and therefore couldn’t have died at such a young and tender age. Her passing gave a sports-

10 The digital girlfriend, Te’o said in an interview last October, two months before he found out the fraud, “was the most beautiful girl I ever met. Not because of her physical beauty, but the beauty of her character and who she is.”

Her character. Remember, she’s an avatar, at best. Again, let’s assume this august institution of higher learning and moral discipline, and all its representatives, are now telling the truth. Then let’s look at this person with the extraordinary character, the woman Te’o fell for. There was a picture, from their online encounters, of a lovely woman, a Stanford student, supposedly. There was a voice, from telephone conversations, of someone as well. And that someone finally called him up in early December and said the whole thing was a hoax perpetuated by an acquaintance in California, according to Deadspin, which broke the story.

“The pain was real,” said Swarbrick. “The grief was real. The affection was real. That’s the nature of this sad, cruel game.”

810

No, that’s the nature of people who develop relationships through a screen. The Internet is the cause of much of today’s commitment-

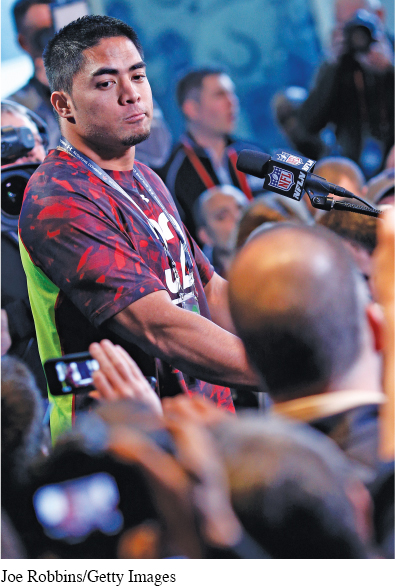

Manti Te’o faced extraordinary media attention after the news of his story came out.

To fall in love requires a bit of unpredictable human interaction. You have to laugh with a person, test their limits, go back and forth, touch them, reveal something true about yourself. You have to show some vulnerability, some give and take. At the very least, you have to make eye contact. It’s easier to substitute texting, tweeting or Facebook posting for these basic rituals of love and friendship because the digital route offers protection. How can you get dumped when you were never really involved?

15 “If anything good comes from this,” said Te’o in a written statement, “I hope it is that others will be far more guarded when they engage people online than I was.”

Te’o called himself a victim of an elaborate hoax. If he’s telling the truth, he’s right in one sense, but wrong in his conclusion. He’s a victim of his age, people who are more willing to embrace fake life through a screen than the real world beyond their smartphone.

Understanding and Interpreting

Throughout the piece, Egan draws a comparison between “digital life” and “real life.” What does he conclude about the differences between them?

Explain the analogy that Egan makes between a mail-

order bride and online dating. How does it support his position on Te’o? It’s clear from the outset that Egan is opposed to the possibility of finding a sustainable, long-

term relationship solely online. What is the most convincing evidence that Egan uses to support his position? What is his least effective evidence? Near the end of the piece, Egan asserts, “To fall in love requires a bit of unpredictable human interaction. You have to laugh with a person, test their limits, go back and forth, touch them, reveal something true about yourself. You have to show some vulnerability, some give and take. At the very least, you have to make eye contact” (par. 14). Which of these conditions are possible and which are impossible online? How does Egan’s definition strengthen or weaken his argument against online relationships?

Even though Manti Te’o likely was tricked and targeted because he played for a high-

profile football team, Egan still calls his story a “compelling parable of digital dating culture” (par. 7). What lessons does he want his readers to draw from Te’o’s story?

Analyzing Language, Style, and Structure

Egan ends his first two paragraphs with rhetorical questions. How does his choice connect the story in the first paragraph with Manti Te’o?

How does Egan reveal his attitude toward Notre Dame through the following passages?

“If Notre Dame wasn’t the land of leprechauns, Win-

One- for- the- Gipper mythology, Rudy and Touchdown Jesus, I might be more inclined to believe Te’o” (par. 6). “Again, let’s assume this august institution of higher learning and moral discipline, and all its representatives, are now telling the truth” (par. 11).

Look back at the places that Egan quotes directly from the press conference by Jack Swarbrick, Notre Dame’s athletic director. How does Egan use Swarbrick’s words to set up his response to them?

Egan often takes a derisive tone toward communication on the Internet. Locate two words or phrases that create this derisive tone and rewrite them, choosing words that might be used by someone with a more positive attitude toward Internet communication.

811

Connecting, Arguing, and Extending

The release of the 2010 documentary film Catfish and a reality television show on MTV by the same name has made the term “catfish” a common way to describe people who lure others into fake online relationships. Watch the documentary or an episode of the show and explain how it either confirms or rejects Egan’s attitude toward online relationships.

In a study published in 2012 by the Internet security firm McAfee, 12 percent of teenage girls reported that they had met in real life with someone they met online, without fully confirming their identity prior to the meeting. Write an argument for rules or guidelines that you think teenagers ought to use when meeting face-

to- face with people they have only met online. Explain how these rules would or would not satisfy Egan’s definition of a real relationship. Do you think it is possible to fall in love with someone you have met online but not in person? Why or why not? What would Egan say about your response?