Chapter 14. Pluto, King of the Kuiper Belt

14.1 Introduction

Author: Scott Miller, Pennsylvania State College

Editor: Grace L. Deming, University of Maryland

The goals of this module: After completing this exercise, you should be able to:

- Explain how Pluto was discovered serendipitously.

- Describe the basic characteristics of Pluto and its moon Charon.

- List the criteria necessary for an object in our solar system to be considered a planet.

In this module you will explore:

- How the discovery of Charon allowed astronomers to determine some general characteristics of Pluto.

- How the discovery of Kuiper Belt Object 2003 UB313 led to the precise defining of the term "planet".

- Why astronomers no longer consider Pluto to be a major planet.

Why are you doing it: Between 1930 and 2006, Pluto was considered the ninth planet of our solar system. Recently, to the dismay of many, Pluto was demoted from major planet status. For some reason, this struck a nerve with many people, who did not like to see Pluto treated in such a manner. In order to understand why the reclassification of Pluto was necessary, you need to understand the circumstances surrounding its discovery and classification as a planet, as well as its reclassification as a dwarf planet.

14.2 Background

After Neptune was discovered in 1846 based on perturbations in Uranus' orbit, astronomers realized that Neptune's existence wasn't enough to account for all of the perturbations. In addition, astronomers noted deviations in Neptune's orbit as well. This led astronomers to suggest the existence of a ninth planet beyond Neptune, which they began to refer to as Planet X.

One of the most ardent seekers of Planet X was American astronomer Percival Lowell, who searched diligently for the planet up until his death in 1916. It wasn't until 14 years later that another American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh discovered Pluto. Tombaugh searched countless photographic plates in search of this elusive planet until he ultimately found it in 1930, 6° away from where he predicted it should be.

The photos above taken one day apart show the motion of Pluto relative to background stars (the area of sky covered in each image is roughly 10 arcminutes by 20 arcminutes). The red arrow in each figure points to Pluto. Compare its position in each frame to the positions of the background stars. Pluto only moves around 1 arcminute per day relative to background stars (1 arcminute is equal to 1/60th of a degree).

Any object discovered in our solar system must be cleared by the International Astronomical Union (IAU), and they will ultimately decide if it should be considered a planet. When Clyde Tombaugh found "Planet X", astronomers hurried to have it designated as the ninth planet in our solar system (and the first one discovered by an American!) After the IAU designated it a planet, the object was given the name of Pluto, the Roman god of the underworld, considering how distant it is from the Sun. It was also given this name in honor of Percival Lowell, whose initials are represented by the first two letters in Pluto, and who searched for it for so long.

Question 14.1

b6QcjcpXNc0SlWVXjcArgLoSp2eHJ8jfXxxpOFiYi/TbHMaIWaznBlm0BpCkhTcgR3DQgL1+YtDMDr1ZEpYhGPy/alRitJwOmnUfZFJygO48DOdHdL6zw6ADkReKobHqY14qf3iREgBDLktVwDlASUY1hDD/idh+/wq9mmy3B2ZFcViCar8e1yjXyD/7xkjqzj8Erg==14.3 A Planet Like No Other

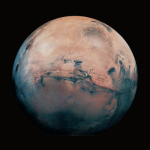

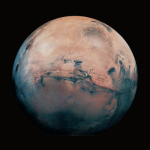

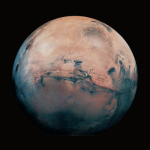

After the discovery of Pluto, astronomers continued to observe this new planet in order to learn more about it. Once they were able to determine its orbital path, they realized that its orbit was unlike that of any other planet. First, most of the planets in our solar system have orbits which lie close to the ecliptic plane (the plane along which the Earth moves as it orbits the Sun). The most inclined planet relative to the ecliptic is Mercury, with an inclination of only 7°. Pluto's orbit is inclined 17° relative to the ecliptic. Second, most of the planets in our solar system have near-circular orbits (their closest approach to the Sun and farthest approach from the Sun isn't that different). Mercury's orbit is the most elliptical, varying from 0.31 AU to 0.47 AU. in distance from the Sun. Pluto’s orbit is more eccentric. Its eccentricity is large enough that while its closest approach to the Sun is 30 AU, its farthest approach from the Sun is 50 AU!

Because Pluto's orbit is so eccentric, it actually passes closer to the Sun than Neptune for 20 years out of every 248-year orbit. The last time this occurred was between 1979 and 1999. If Pluto moves closer to the Sun than Neptune once every orbit, does this mean that there is a possibility that they will collide? To find out, watch the animation below:

Question 14.2

jdpsdMxb5GCFzPqWD1YfGe+6NzrJOjptBpCcbegcCKfUTobLLOtwcILk3yFdHqbOCdAeNRy8mA3JedepQzPSC+Vp6mgnLZLYSauxhnbB+gZOheNIcG3h2XSfY5o=Summary

There are two reasons why Pluto and Neptune will never collide. First, during the period when Pluto is closer to the Sun than Neptune, that is also the time when Pluto is farthest away from the ecliptic plane. Neptune's orbit is barely inclined relative to the ecliptic, so during this period, Pluto's path is too far above Neptune's path, relative to the ecliptic, for a collision to occur. Second, Pluto's orbital period is in resonance with Neptune's orbit. A resonance is when two orbital periods are related to each other by an integer value. In the case of Pluto and Neptune, they share a 2:3 resonance; every time Pluto orbits the Sun twice, Neptune orbits exactly 3 times. Because of this, they will never be in the same location (even if their orbits weren't inclined).

14.4 The Moons of Pluto

In 1978, astronomers discovered that Pluto had a moon. It was named Charon, after the ferryman of the underworld who carried dead souls across the river Styx.

Question 14.3

yiGaVazMi/R1Dntirfzraijt9lpprYq30qaMKrt4S2vLSFlaMDGlUbeqguqelterHKYMUEkHoEHdntLfZWIRPpf+kB/DsqxTofCyK0fo+xG+f60pKWr8R23lmaEieBy6BES1fU/yYU2LmFIRssm6ylfLbCY94kYYiHnt2/9PjE3ol1osNvU3RqAq9lQlFc83NaHVq6Wex0zJ4a9CFyolLbHcNOPBFwTjOI/5NnO77UFXH89pXI3c0s4aqjyZRhz8GiTL08evP9olkwe+F4+4weLAib9yFtghNGHqA4+FDOToOPNdyxBkRj4B6916Sd5Q8tPUonem8xp9Mm/xdsr3BpHY2sgQKMO/0WEfuXXzJdmn7t9Hpu6qu3BCnK8uNjfBrqkF+ceJBt3Iih+Rfva/dw0oLHaClizmo0h/J3psKhtHF8r9u82cgSk0lishyT3gtVRPq4dLm6a6tL7mET91b8+zh2SMw5qKR9ovq5Cd79dkDFQ4PqMXndrQnXfIQ4SAnkdPTa4+4IjEM+u5H6l2QVzDU6ZbXfZBm/R/+HcTb+3wwN5u9Pr3BU9awR5eGOsqsDR1iBfHkSuO8RHubFYyaVT7RyHsgb/aBH5NJRxTOqv6mmKaNyH6oTmxZkkZ/wuNPW/tkFgfqrajPw5nl+rFJ6kIPqyXjeGNMrZO4swK4kW4+UZ8xl39gwym58i9XBhbhoBPQV6yKxi9ZfNHnmUBrDGAxZQ4qLctkN/aTxTwPjGXKJWhtfDv/Wap5xH6kHh98JEjUw==Summary

By noting Charon's orbit around Pluto, astronomers were able to determine the masses of these two objects. Pluto is only eight times as massive as Charon. In fact, Pluto's mass is smaller than some of the largest Galilean moons. In other words, Pluto is by no means massive enough to cause any perturbations in the orbits of Neptune or Uranus. Upon further analysis of their orbits, astronomers determined that the deviations they detected were actually mathematical errors. In looking for something that actually shouldn't be there, astronomers serendipitously discovered something else.

Charon is half Pluto's diameter. The pair is more closely matched in mass and size than any planet-moon combination in our solar system.

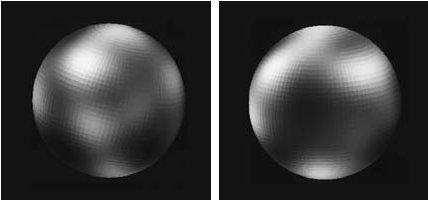

Upon determining Pluto's size and mass, astronomers were able to calculate Pluto's density, and find that it only has a density of 1.8 g/cm3 (or 1800 kg/m3). This suggests that Pluto is roughly 50/50 ice and rock, quite unlike the terrestrial planets (rocky bodies with densities around 4 to 5 g/cm3) or the jovian planets (huge gaseous planets with densities close to 1 g/cm3), but much more like comets. Recent Hubble Space Telescope observations suggest that Pluto has bright polar caps of ice, while spectroscopic studies of Pluto's absorption spectrum suggests that its surface is covered with various ices, such as nitrogen, methane, and carbon monoxide.

14.5 The Moons of Pluto - continued

Because Charon is the largest moon relative to its planet, it is not accurate to say that Charon orbits around Pluto, but rather that Pluto and Charon orbit around a common center of mass, as you can see in the video to the right.

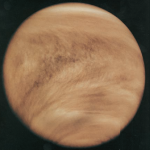

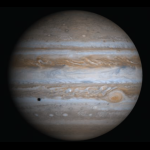

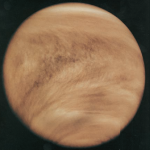

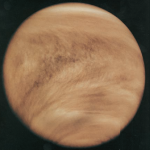

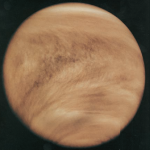

Also, due to the small difference in their masses, Pluto and Charon are tidally locked to each other in synchronous rotation. As they orbit around each other, each one always presents the same side to the other. Their rotation rate is equal to their orbital rate, only 6.4 days long. Both Pluto and Charon also have rotation axes, which are tilted more than 90 degrees relative to their orbital path. This means that Pluto undergoes retrograde rotation, similar to Venus and Uranus.

Question 14.4

EPoEst4K559ixk0IKgUuLMx/Th50xcv0BajJ6ctJ02NvwdGhVAh4MbIK+1RxF9Amf20O6ZPR0YTKsKmphb3sRAhGtA1wJq/NU/0ksxrGmC2vOl1UK+K/mBcdXZfEvbt22K/xU8QXL50fYVXtpMCAmvrWdKNMe2x2BFG2XISHS2OIL8tlonDdCseD8b//Pw2xIobZNvGvVBFuitR2Cai0T0rfCgKrHeVtGPu+blODYK+Bhdnq2B4ATB2pGx8h78xBsW9BZQ==Summary

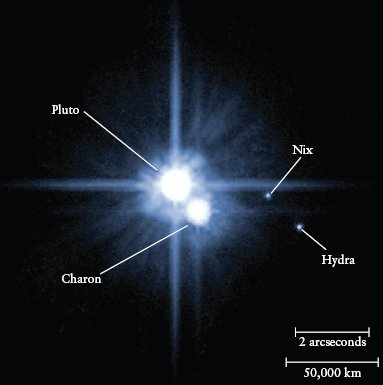

In 2005, astronomers discovered two more moons orbiting Pluto, using the Hubble Space Telescope. These moons, shown in the photo above, are now known as Nix and Hydra. While much smaller than Charon, Nix and Hydra are very similar to Charon in terms of composition and color. As of 2015, Pluto is known to have five moons.

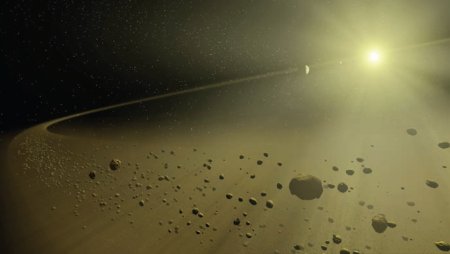

14.6 Discovery of Kuiper Belt Objects

One of the reasons why astronomers were willing to name Pluto the ninth planet of the solar system is because, at the time of its discovery in 1930, it was the only object ever detected that far away from the Sun. It wasn't until the 1940's and 50's that American astronomer Kuiper and British astronomer Eddington began theorizing that there may be other objects farther away from the Sun than Neptune - an entire system of objects which was referred to as Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs). Still, while astronomers believed that other objects may exist out there, none were discovered for a long time.

It wasn't until 1992 that the first KBO was discovered. Astronomers now refer to that object as 1992 QB1 (its official designation based on when it was discovered). Since then, over 1000 KBOs have been discovered, all smaller than Pluto. These objects appeared to be part of the Kuiper Belt; a region similar to the Asteroid Belt in that it contained objects in orbit around the Sun in or near the ecliptic plane. The Kuiper Belt occupies a region from roughly 30 AU to 50 AU in radius, centered on our Sun. KBOs seem to come in three varieties: Classical KBOs - which have near-circular orbits like the planets; Scattered KBOs - which have more elliptical orbits which send them outside of the Kuiper Belt for part of their orbits; and Plutinos - which are KBOs that share a 2:3 resonance with Neptune, just like Pluto. Where Pluto once was an oddity in our solar system, it now appeared as if it found its place in our solar system as the King of the Kuiper Belt.

Question 14.5

To3im21FFu+8nQtZT7TdoOPdHr7d6C8PsTrIKTf5rwnMqXfbsxqDSPBquqW9Dxghx0Bs6zGYxhLGjSIvIB4/Lkqa6Yf3mzI7jDhsvXVlXKRpjqurRYlPUJjFhHOwPGDV45kZg68RyXyaCx2Y3jdMwG9Ou2hrtrz1mymkuYMXrezrMjHv1zoiUBPaidoKL9gSU1suhkDoGfZS850Y+9ozewMRziUNYe3Qim7Z7syMdywQn/6d0okHiTS2hH6VvuEwSummary

With the discovery of so many Kuiper Belt Objects, astronomers began to wonder if any of them should be considered a planet, or if Pluto should simply be considered the largest of the Kuiper Belt Objects. The trouble was that there was no official scientific definition for the term "planet". Up until this point, there didn't seem to be a need for one. However, back in the 1800's, a similar problem had occurred with the discovery of Ceres, the largest asteroid in the Asteroid Belt. When it was first discovered, astronomers didn't know about the Asteroid Belt, and so they called Ceres a planet. It was soon discovered afterwards, though, that many more asteroids existed, and so Ceres was demoted to an asteroid. With Pluto, though, it had been considered a planet for a much longer time, and the general public (and many astronomers) was hesitant to demote it from planetary status.

14.7 What is a planet?

Everything changed, though, in 2005 with the discovery of 2003 UB313. Classified as a Scattered KBO currently at a distance of 38 AU, 2003 UB313 is larger than Pluto. Astronomers were using the arbitrary definition that a planet should be Pluto-sized or larger in order to discount the other KBOs, but with the discovery of 2003 UB313, they could no longer do so. The question among astronomers became, should we call 2003 UB313 the tenth planet (and expect that with increases in technology that it will only be a matter of time before we discover more objects near this size), or should the astronomical community decide on an official definition for the term "planet"? In August of 2006, the IAU and over 400 of its members met to decide on this issue.

At the 2006 meeting of the IAU (International Astronomical Union), the astronomical community voted on and accepted the following definition for the term "planet":

- A planet must orbit directly around the Sun.

- A planet must have sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape.

- A planet must have sufficient gravity such that it has cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.

View the following animation of our solar system. Click on all of the different views to get a feel for how the various objects in our solar system orbit. Afterwards we will investigate for ourselves which objects should be considered planets.

Open animation in new window

NOTE: This is an outside application that works best in Internet Explorer or Windows 7.

Question 14.6

Of the objects shown below, which of them directly orbit around the Sun (and not around another object)? Choose "yes" or "no" for each object.

Mercury

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Venus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Earth

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Moon

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Mars

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Mathilde

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Ceres

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Jupiter

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Ganymede

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

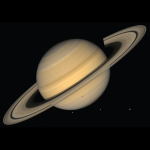

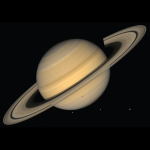

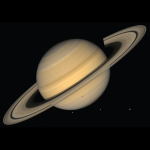

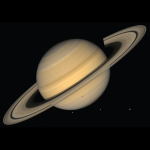

Saturn

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

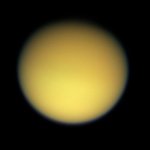

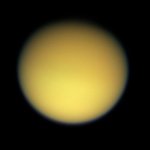

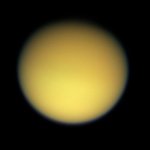

Titan (a moon of Saturn)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

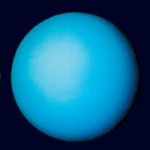

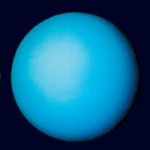

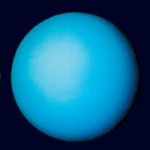

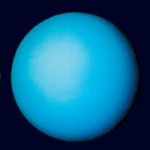

Uranus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

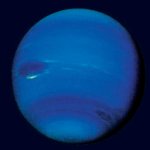

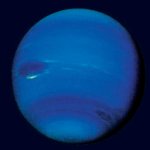

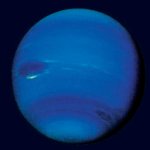

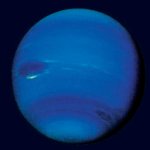

Neptune

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Triton (a moon of Neptune)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Pluto

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Charon (a moon of Pluto)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

2003 UB313 (a Kuiper Belt Object)

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

14.8 What is a planet? - continued

Question 14.7

Of the objects listed below, which of the following has a nearly spherical shape? Choose "yes" or "no" for each object.

Mercury

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Venus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Earth

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Moon

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

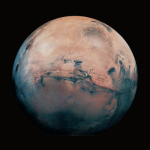

Mars

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Mathilde

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Ceres

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

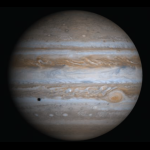

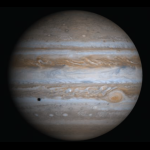

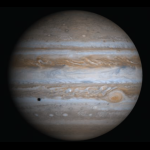

Jupiter

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Ganymede

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Saturn

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Titan (a moon of Saturn)

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Uranus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Neptune

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Triton (a moon of Neptune)

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Pluto

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Charon (a moon of Pluto)

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

2003 UB313 (a Kuiper Belt Object)

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

14.9 What is a planet? - continued

Question 14.8

Of the objects listed below, which of the following have “cleared their local neighborhood”? [Hint: which of the following do not orbit near other objects of comparable size to itself?] Choose "yes" or "no" for each object.

Mercury

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Venus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Earth

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Moon

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Mars

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Mathilde

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Ceres

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Jupiter

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Ganymede

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Saturn

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Titan (a moon of Saturn)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Uranus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Neptune

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Triton (a moon of Neptune)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Pluto

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Charon (a moon of Pluto)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

2003 UB313 (a Kuiper Belt Object)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

14.10 What is a planet? - continued

Question 14.9

Based on the three criteria, which of the following should be considered a major planet? Choose "yes" or "no" for each object.

Mercury

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Venus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Earth

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Moon

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Mars

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Mathilde

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Ceres

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Jupiter

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Ganymede

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Saturn

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Titan (a moon of Saturn)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Uranus

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Neptune

|

/VQlYHIBOXnjb5qb9niyDPFA3ZTYTYPv |

Triton (a moon of Neptune)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Pluto

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

Charon (a moon of Pluto)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

2003 UB313 (a Kuiper Belt Object)

|

UHDy5PaHfQdz60p0GrVwfatusi2fOVr/ |

14.11 Pluto: A Dwarf Planet

Question 14.10

iderbnKhQQ7jtnqjcp/U3KbUgdek6kz8cZx6/zNM8Hdu2JJQlqajM+thITLg/Wbf4264jfnz5fk4EG7IvQfnMbEdWkDe3uPHAHsKMQExmQKHy1Z4GaeHIKWU0MT7Pz6WEyF72YlGuSqiBCrIo0eCjp8mekOCQ8BaBuxGQh7CpBpM5nbuneIGQphvFNhb/MtIhmMYWELKLTT7aG4oeSV1WLrhDisaA0FdUJ0ZXZipYBsfB1r9ptJkmKRadR70svtk5gaevXhHmHPRC+RkOSQkm8rRHBNi+X2NBphIi+SI9Sya5cCeyIirqlJAun5VzONqLvRyTxHUX/pKse+O867XzpoBzfIFIqQlSummary

According to the IAU, Pluto is now considered a dwarf planet. A dwarf planet is any object which orbits directly around the Sun, has pulled itself into a near-spherical shape, but has not cleared its local neighborhood. Two other objects have also been classified as dwarf objects: Ceres and 2003 UB313, which has now been officially named Eris. While the IAU has only officially classified three objects as dwarf planets, we know of many more objects which satisfy these criteria, and it is only a matter of time before the number of dwarf planets increases dramatically.

14.12 Quick Check Quiz

Indepth Activity: Pluto, King of the Kuiper Belt