Instructor Notes

See the Additional Resources for Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing and reading comprehension quizzes for this chapter.

3

1

Critical Thinking

What is the hardest task in the world? To think.

— RALPH WALDO EMERSON

In all affairs it’s a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.

— BERTRAND RUSSELL

Although Emerson said the hardest task in the world is simply “to think,” he was using the word think in the sense of critical thinking. By itself, thinking can mean almost any sort of cognitive activity, from idle daydreaming (“I’d like to go camping”) to simple reasoning (“but if I go this week, I won’t be able to study for my chemistry exam”). Thinking by itself may include forms of deliberation and decision-making that occur so automatically they hardly register in our consciousness (“What if I do go camping? I won’t be likely to pass the exam. Then what? I better stay home and study”).

When we add the adjective critical to the noun thinking, we begin to examine this thinking process consciously. When we do this, we see that even our simplest decisions involve a fairly elaborate series of calculations. Just in choosing to study and not to go camping, for instance, we weighed the relative importance of each activity (both are important in different ways); considered our goals, obligations, and commitments (to ourselves, our parents, peers, and professors); posed questions and predicted outcomes (using experience and observation as evidence); and resolved to take the most prudent course of action.

Many people associate being critical with fault-finding and nit-picking. The word critic might conjure an image of a sneering art or food critic eager to gripe about everything that’s wrong with a particular work of art or menu item. People’s low estimation of the stereotypical critic comes to light humorously in Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot, when the two vagabond heroes, Vladimir and Estragon, engage in a name-calling contest to see who can hurl the worst insult at the other. Estragon wins hands-down when he fires the ultimate invective:

V: Moron!

E: Vermin!

V: Abortion!

4

E: Morpion!

V: Sewer-rat!

E: Curate!

V: Cretin!

E: (with finality) Crritic!

V: Oh! (He wilts, vanquished, and turns away)

However, being a good critical thinker isn’t the same as being a “critic” in the derogatory sense. Quite the reverse: Because critical thinkers approach difficult questions and seek intelligent answers, they must be open-minded and self-aware, and they must interrogate their own thinking as rigorously as they interrogate others’. They must be alert to their own limitations and biases, the quality of evidence and forms of logic they themselves tentatively offer. In college, we may not aspire to become critics, but we all should aspire to become better critical thinkers.

Becoming more aware of our thought processes is a first step in practicing critical thinking. The word critical comes from the Greek word krinein, meaning “to separate, to choose”; above all, it implies conscious inquiry. It suggests that by breaking apart, or examining, our reasoning we can understand better the basis of our judgments and decisions — ultimately, so that we can make better ones.

Thinking through an Issue: Gay Marriage Licenses

By way of illustration, let’s examine a case from Kentucky that was reported widely in the news in 2015. After the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark decision making gay marriage legal in all fifty states, a Rowan County clerk, Kim Davis, refused to begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Citing religious freedom as her reason, Davis contended that the First Amendment of the Constitution protects her from being forced to act against her religious convictions and conscience. As a follower of Apostolic Christianity, she believes gay marriage is not marriage at all. To act against her belief, she said, “I would be asked to violate a central teaching of Scripture and of Jesus Himself regarding marriage…. It is not a light issue for me. It’s a Heaven or Hell decision.”

Let’s think critically about this — and let’s do it in a way that’s fair to all parties and not just a snap judgment. Critical thinking means questioning not only the beliefs and assumptions of others, but also one’s own beliefs and assumptions. We’ll discuss this point at some length later, but for now we’ll say only that when writing an argument you ought to be thinking — identifying important problems, exploring relevant issues, and evaluating available evidence — not merely collecting information to support a pre-established conclusion.

In 2015, Kim Davis was an elected county official. She couldn’t be fired from her job for not performing her duties because she had been placed in that position by the vote of her constituency. And as her lawyers pointed out, “You don’t lose your conscience rights, or your religious freedom rights, or your constitutional rights just because you accept public employment.” However, once the Supreme Court established the legality of same-sex marriage, Davis’s right to exercise her religious freedom impinged upon others’ abilities to exercise their equal right to marriage (now guaranteed to them by the federal government). And so there was a problem: Whose rights have precedence?

5

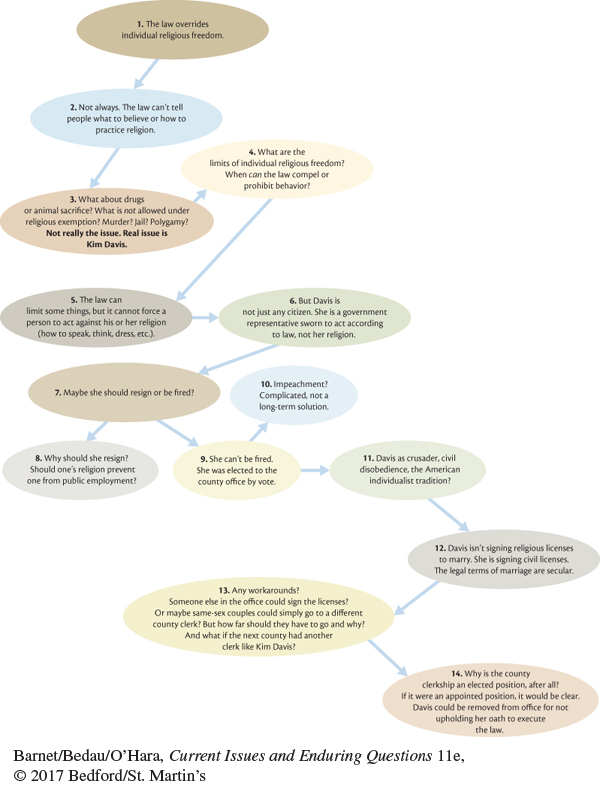

We may begin to identify important problems and explore relevant issues by using a process called clustering. (We illustrate clustering again in Generating Ideas: Writing as a Way of Thinking.) Clustering is a method of brainstorming, a way of getting ideas on paper to see what develops, what conflicts and issues exist, and what tentative conclusions you can draw as you begin developing an argument. To start clustering, take a sheet of paper, and in the center jot down the most basic issue you can think of related to the problem at hand. In our example, we wrote a sentence that we think gets at the heart of the matter. It’s important to note that we conducted this demonstration in “real time” — just a few minutes — so if our thoughts seem incomplete or off-the-cuff, that’s fine. The point of clustering is to get ideas on paper. Don’t be afraid to write down whatever you think, because you can always go back, cross out, rethink. This process of working through an issue can be messy. In a sense, it involves conducting an argument with yourself.

At the top of our page we wrote, “The law overrides individual religious freedom.” (Alternatively, we could have written from the perspective of Davis and her supporters, saying “Individual religious freedom supersedes the law,” and seen where that might have taken us.) Once we have a central idea, we let our minds work and allow one thought to lead to another. We’ve added numbers to our thoughts so you can follow the progression of our thinking.

6

7

Notice that from our first idea about the law being more important than individual religious freedom, we immediately challenged our initial thinking. The law, in fact, protects religious freedom (2), and in some cases allows individuals to “break the law” if their religious rituals require it. We learned this when we wrote down a number of illegal activities sometimes associated with religion, and quickly looked up whether or not there was a legal precedent protecting these activities. We found the Supreme Court has allowed for the use of illegal drugs in some ceremonies (Gonzalez v. O Centro Espirita), and for the ritual sacrifice of animals in another (Church of Lakumi Bablu Aye v. Hialeah). Still, religions cannot do anything they want in the name of religious freedom. Religions cannot levy taxes, or incarcerate or kill people, for example. We then realized that what religions do as part of their ceremonies is not really the issue at all. The questions we are asking have to do with Kim Davis, her individual religious freedom, and what the law might force her to do (4).

Individuals cannot simply break the law and claim religious exemption. But the government cannot force people to act against their religious beliefs (5). Then (6) it occurred to us that Davis isn’t just any citizen but a government employee whose job is to issue marriage licenses under the law. She may be free to believe what she wants and exercise her rights accordingly, but she cannot use her authority legally as a government official to deny people the rights they’ve been afforded by law.

We then posed several questions to ourselves in trying to determine the right way to think. We considered whether Davis should resign or be fired (7), which we then realized isn’t possible (8, 9), and we wondered how else a person may be removed from office (10). We considered her as a figure of civil disobedience, defying the law in defense of religious liberties (11), trying to see the situation from her perspective. But we returned again to the idea that she isn’t just a regular citizen but an agent of the law whose oath compels her to uphold the law (6). She shouldn’t be able to use her authority to deprive others of exercising their rights. We also considered that the government doesn’t take particular interest in the religious basis of marriage (12), so why should Davis be permitted to impose her religious beliefs on a lawful act of marriage?

By the time we got to (13), we thought, “Isn’t there some workaround? Can’t deputy clerks continue to sign the licenses as long as the state accepts them?” This way, Davis wouldn’t have to violate the deeply held beliefs that she is free to hold, and yet those seeking to exercise their rights to marriage would still be satisfied. Later, on page 374, we discuss a facet of compromise solutions to difficult problems when we explore Rogerian argument (named for Carl Rogers, a psychologist), a way of arguing that promotes finding common ground and solutions in which both sides win by conceding some elements to the opposition. We also thought in (13) that maybe same-sex couples could just get their licenses from a different place, one where Davis doesn’t work.

At this point, it may be useful to mention another facet of critical thinking and argument that we’ll also explore in more detail later: considering the implications of the decisions to which our thinking leads. What happens when our judgments on matters are settled and we draw a reasonable conclusion? If we were to settle on a compromise in the Davis case, it might work for the moment, but what would happen if other clerks in the state held the same beliefs as Davis (13)? In (13), we also considered the implications if same-sex couples were simply asked to go to a different office. How far should a same-sex couple have to go to find someone willing to issue the license if all clerks can decide based on their religious convictions what kinds of marriage they will authorize? Additionally, and maybe even more important, why should same-sex couples be hindered in any way in acquiring their license or be treated as a different class of citizens?

8

Again, if you think with pencil and paper in hand and let your mind make associations by clustering, you’ll find (perhaps to your surprise) that you have plenty of interesting ideas and that some can lead to satisfying conclusions. Doubtless you’ll also have some ideas that represent gut reactions or poorly thought-out conclusions, but that’s okay. When clustering, allow your thoughts to take shape without restriction; you can look them over again and organize them later. Originally, we wrote in our cluster (7) that Davis could be fired for not performing her job according to its requirements. We then realized that this wouldn’t involve a simple process. Because she’s an elected official, there would have to be a state legislative action to impeach her (9). This made us think, “The state of Kentucky could impeach Davis” (10). But then we also considered the consequences and decided this would not be a long-term solution. What if the next election cycle brought someone else who shares Davis’s beliefs into the same position? In fact, what if citizens in Kentucky continued to elect county clerks in Rowan County — or any county — who refused to issue marriage licenses based on religious convictions? Would the state have to impeach clerks over and over again? We then thought, “Why is the county clerkship an elected position” (14)? Could it become an appointed position instead, such that governors could emplace county clerks, whose primary job is to administer legislative policy? Perhaps this is the argument we’ll want to make. (Of course, it might open up new questions and issues that we would have to explore: What else does the clerk do? Is the autonomy of an elected position necessary? Do all states elect county clerks? And so on.)

A RULE FOR WRITERS One good way to start writing an essay is to generate ideas by clustering — and at this point not to worry that some ideas may be off-the-cuff or even nonsense. Just get ideas down on paper. You can evaluate them later.

At the time of this writing, Kim Davis had continued to refuse signing marriage licenses for same-sex couples. When ordered by a judge to do so or face contempt of court, she held firm to her position and spent six days in jail as a result. Her supporters cheered her act of civil disobedience (defined as breaking a law based on moral or religious conscience) and even compared her to Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and other civil rights leaders who fought against unjust laws on the basis of religious principles. Davis returned to her position as Rowan County clerk and authorized her deputy clerks to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples, but without her signature. Time will tell how the case plays out.

Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing

As noted, some of Kim Davis’s supporters have compared her to celebrated figures from American history like Rosa Parks who practiced civil disobedience by breaking laws they believed were immoral, unfair, or unjust. What are the similarities and differences in the case of Rosa Parks, who violated the law in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 by refusing to move to the “black” section of a public bus, and that of Kim Davis, who has refused to abide by laws established by the U.S. Supreme Court regarding gay marriage? How do the similarities and differences justify or not justify Davis’s actions?

9

On a Facebook page dedicated to Davis’s case, one commenter wrote, “Davis is a hero for all of us Christians who feel this country is abandoning our God.” Think critically about this statement by writing about the assumptions it reveals.

In denying Davis’s appeal to a federal court to not be forced to authorize same-sex marriage licenses, Judge David Bunning wrote that individuals “cannot choose what orders they follow” and that religious conscience “is not a viable defense” for not adhering to the law. At the same time, the free exercise clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution says that Congress shall make no law prohibiting the free exercise of religion. What do you think about Kim Davis’s exercise of religion? Is it fair that in order to keep her job after the Court’s decision about the legality of gay marriage, she has to regularly violate one of her religion’s central beliefs about marriage? Explain your response.