On Flying Spaghetti Monsters: Analyzing and Evaluating from Multiple Perspectives

Let’s think critically about another issue related to religious freedom, equality, and the law — one that we hope brings some humor to the activity but also inspires careful thinking and debate.

In 2005, in response to pressure from some religious groups, the Kansas Board of Education gave preliminary approval for teaching alternatives to evolution in public school science classes. New policies would require science teachers to present “intelligent design” — the idea that the universe was created by an intentional, conscious force such as God — as an equally plausible explanation for natural selection and human development.

In a quixotic challenge to the legislation, twenty-four-year-old physics graduate Bobby Henderson wrote an open letter that quickly became popular on the Internet and then was published in the New York Times. Henderson appealed for recognition of another theory that he said was equally valid: that an all-powerful deity called the Flying Spaghetti Monster created the world. While clearly writing satirically on behalf of science, Henderson nevertheless kept a straight face and argued that if creationism were to be taught as a theory in science classes, then “Pastafarianism” must also be taught as another legitimate possibility. “I think we can all look forward to the time,” he wrote, “when these three theories are given equal time in our science classes…. One third time for Intelligent Design; one third time for Flying Spaghetti Monsterism (Pastafarianism); and one third time for logical conjecture based on overwhelming observable evidence.”

10

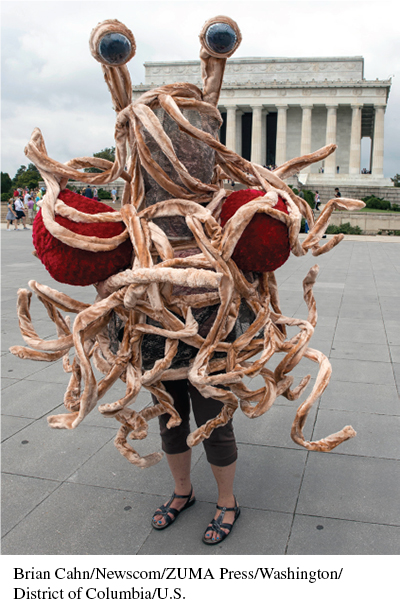

Since that time, the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster has become a creative venue where secularists and atheists construct elaborate mythologies, religious texts, and rituals, most of which involve cartoonish pirates and various noodle-and-sauce images. (“R’amen,” they say at the end of their prayers.) However, although tongue-in-cheek, many followers have also used the organization seriously as a means to champion the First Amendment’s establishment clause, which prohibits government institutions from establishing, or preferring, any one religion over another. Pastafarians have challenged policies and laws in various states that appear to discriminate among religions or to provide exceptions or exemptions based on religion. In Tennessee, Virginia, and Wisconsin, church members have successfully petitioned for permission to display statues or signs of the Flying Spaghetti Monster in places where other religious icons are permitted, such as on state government properties. One petition in Oklahoma argued that because the state allows a marble and granite Ten Commandments monument on the state courthouse lawn, then a statue of the Flying Spaghetti Monster must also be permitted; this effort ultimately forced the state to remove the Ten Commandments monument in 2015. In the past three years, individuals in California, Georgia, Florida, Texas, California, and Utah have asserted their right to wear religious head coverings in their driver’s license photos — a religious exemption afforded to Muslims in those states — and have had their pictures taken with colanders on their heads.

Let’s stop for a moment. Take stock of your initial reactions to the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Some responses might be quite uncritical, quite unthinking: “That’s outrageous!” or “What a funny idea!” Others might be the type of snap judgment we discussed earlier: “These people are making fun of real religions!” or “They’re just causing trouble.” Think about it: If your hometown approved placing a Christmas tree on the town square during the holiday season, and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster argued that it too should be allowed to set up its holiday symbol as a matter of religious equality — perhaps a statue like the one pictured above — should it be afforded equal space? Why, or why not?

Be careful here, and exercise critical thinking. Can one simply say, “No, that belief is ridiculous,” in response to a religious claim? What if members of a different religious group were asking for equal space? Should a menorah (a Jewish holiday symbol) be allowed? A mural celebrating Kwanzaa? A Native American symbol? Can some religious expressions be included in public spaces and not others? If so, why? If not, why not?

11

In thinking critically about a topic, we must try to see it from all sides before reaching a conclusion. We conduct an argument with ourselves, advancing and then questioning different opinions:

What can be said for the proposition?

What can be said against it?

Critical thinking requires us to support our position and also see the other side. The heart of critical thinking is a willingness to face objections to one’s own beliefs, to adopt a skeptical attitude not only toward views opposed to our own but also toward our own common sense — that is, toward views that seem to us as obviously right. If we assume we have a monopoly on the truth and dismiss those who disagree with us as misguided fools, or if we say that our opponents are acting out of self-interest (or a desire to harass the community) and we don’t analyze their views, we’re being critical but we aren’t engaging in critical thinking.

When thinking critically, it’s important to ask key questions about any position, decision, or action we take and any regulation, policy, or law we support. We must ask:

Is it fair?

What is its purpose?

Is it likely to accomplish its purpose?

What will its effects be? Might it unintentionally cause some harm?

If it might cause harm, to whom? What kind of harm? Can we weigh the potential harm against the potential good?

Who gains something and who loses something as a result?

Are there any compromises that might satisfy different parties?

What do you think? If you were on your hometown’s city council, how would you answer the above questions in relation to a petition from the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster to permit a Spaghetti Monster display alongside the traditional Christmas tree on the town square? How would you vote, and why? What other questions and issues might arise from your engagement with this issue? (Hint: Try clustering. Place the central question in the middle of a sheet of a paper, and brainstorm the issues that flower from it.)

CALL-OUT: OBSTACLES TO CRITICAL THINKING Because critical thinking requires engaging seriously with potentially difficult topics, topics about which you may already have strong opinions, and topics that elicit powerful emotional responses, it’s important to recognize the ways in which your thinking may be compromised or clouded. Write down or discuss how each of the following attitudes might impede or otherwise negatively affect your critical thinking in real life. How might each one be detrimental in making conclusions?

The topic is too controversial and will never be resolved.

The topic hits “too close to home” (i.e., “I’ve had direct experience with this”).

12

The topic disgusts me.

The topic angers me.

Everyone I know thinks roughly the same thing I do about this topic.

Others may judge me if I verbalize what I think.

My opinion on this topic is X because it benefits me, my family, or my kind the most.

My parents raised me to think X about this topic.

One of my favorite celebrities believes X about this topic, so I do too.

I know what I think, but my solutions are probably unrealistic. It’s impossible to change the system.

Think of some more obstacles to critical thinking, and provide examples of how they might lead to unsound conclusions or poor solutions.

A RULE FOR WRITERS Early in the process of jotting down your ideas on a topic, stop to ask yourself, “What might someone reasonably offer as an objection to my view?”

In short, as we will say several times (because the point is key), argument is an instrument of learning as well as of persuasion. In order to formulate a reasoned position and make a vote, you’ll have to gather some information, find out what experts say, and examine the points on which they agree and disagree. You’ll likely want to gather opinions from religious leaders, community members, and legal experts (after all, you wouldn’t want the town to be sued for discrimination). You’ll want to think beyond a knee-jerk value judgment like, “No, a Spaghetti Monster statue would be ugly.”

Seeing the issue from multiple perspectives will require familiarizing yourself with current debates — perhaps about religious equality, free speech, or the separation of church and state — and considering the responsibility of public institutions to accommodate different viewpoints and various constituencies. Remember, the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster didn’t gain so much traction by being easy to dismiss. Thus, you must do the following:

Survey, considering as many perspectives as possible.

Analyze, identifying and then separating out the parts of the problem, trying to see how its pieces fit together.

Evaluate, judging the merit of various ideas and claims and the weight of the evidence in their favor or against them.

If you survey, analyze, and evaluate comprehensively, you’ll have better and more informed ideas; you’ll generate a wide variety of ideas, each triggered by your own responses and the ideas your research brings to light. As you form an opinion and prepare to vote, you’ll be constructing an argument to yourself at first, but also one you may have to present to the community, so you should be as thorough as possible and sensitive to the ideas and rights of many different people.

CRITICAL THINKING AT WORK: FROM JOTTINGS TO A SHORT ESSAY

13

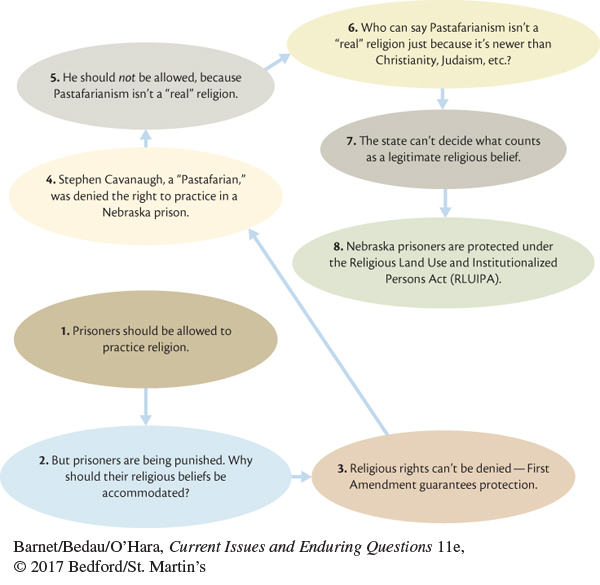

We have already seen an example of clustering in Thinking through an Issue: Gay Marriage Licenses, which illustrates the prewriting process of thinking through an issue and generating ideas by imagining responses — counterthoughts — to our initial thoughts. Here’s another example, this time showing an actual student’s thoughts about an issue related to the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. The student, Alexa Cabrera, was assigned to write approximately 500 words about a specific legal challenge made by a member of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster. She selected the case of Stephen Cavanaugh, a prisoner who made a complaint against the Nebraska State Penitentiary after being denied the right to practice Pastafarianism while incarcerated there. Because the Department of Corrections denied him those privileges, Cavanaugh filed suit citing civil rights violations and asked for his rights to be accommodated. Notice that in the essay — the product of several revised drafts — the student introduced points she had not thought of while clustering. The cluster, in short, was a first step, not a road map of the final essay.