Seeing versus Looking: Reading Advertisements

143

Advertising is one of the most common forms of visual persuasion we encounter in everyday life. The influence of advertising in our culture is pervasive and subtle. Part of its power comes from our habit of internalizing the intended messages of words and images without thinking deeply about them. Once we begin decoding the ways in which advertisements are constructed — once we view them critically — we can understand how (or if) they work as arguments. We may then make better decisions about whether to buy particular products and what factors convinced us or failed to convince us.

To read an advertisement — or any image — critically, it helps to consider some basic rules from the field of semiotics, the study of signs and symbols. Fundamental to semiotic analysis is the idea that visual signs have shared meanings in a culture. If you approach a sink and see a red faucet and a blue faucet, you can be pretty sure which one will produce hot water and which one will produce cold. In a similar way, we almost subconsciously recognize the meanings of images in advertisements. Thus, one of the first strategies we can use in reading advertisements critically is deconstructing them, taking them apart to see what makes them work. It’s helpful to remember that advertisements are enormously expensive to produce and disseminate, so nothing is left to chance. Teams of people typically scrutinize every part of an advertisement to ensure it communicates the intended message — although this doesn’t imply that viewers must accept those messages. In fact, taking advertisements apart is the first step in being critical about them.

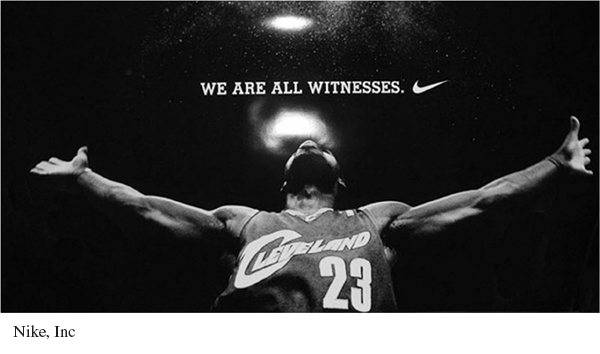

Taking apart an advertisement means examining each visual element. Consider this advertisement for Nike shoes featuring basketball star LeBron James. Already, you should see the celebrity appeal — an implicit claim that Nike shoes help make James a star player. The ad creates an association between the shoes and the sports champion. James’s uniform number, 23, assists in this association by referencing another basketball legend (and Nike spokesperson), Michael Jordan. James is, in a way, presented as the progeny of Michael Jordan, as a new incarnation of a sports “god.” WE ARE ALL WITNESSES, the text reads, drawing on language commonly used in religious settings to describe the second coming of Christ. James’s arms are outstretched, Christ-like, and seem to be illuminated by divine light from above. The uniform also references James’s famous return to the Cleveland Cavaliers, his hometown team, after leaving the team abruptly to play four seasons with the Miami Heat. His “return” to Cleveland — his own second coming — the son of a sports god — and with the resonance of forgiveness, redemption, and salvation for Cleveland sports fans: All these associations work together to elevate James, Jordan, and Nike to exalted status. Of course, our description here is tongue-in-cheek. We’re not gullible enough to believe this literally, and the ad’s producers don’t expect us to be; but they do hope that such an impression will be powerful enough to make us think of Nike the next time we shop for athletic shoes. If sports gods wear Nike, why shouldn’t we?

144

This kind of analysis is possible when we recognize a difference between seeing and looking. Seeing is a physiological process involving light, the eye, and the brain. Looking, however, is a social process involving the mind. It suggests apprehending an image in terms of symbolic, metaphorical, and other social and cultural meanings. To do this, we must think beyond the literal meaning of an image or image element and consider its figurative meanings. If you look up apple in the dictionary, you’ll find its literal, denotative meaning — a round fruit with thin red or green skin and a crisp flesh. But an apple also communicates figurative, connotative meanings. Connotative meanings are the cultural or emotional associations that an image suggests.

145

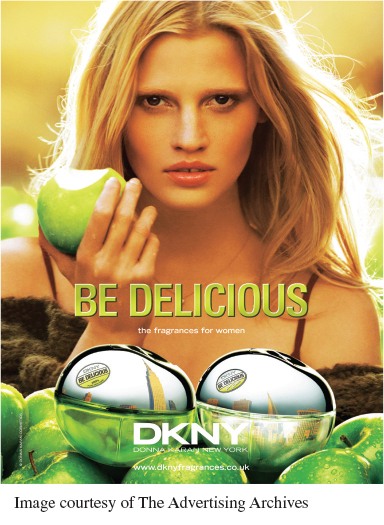

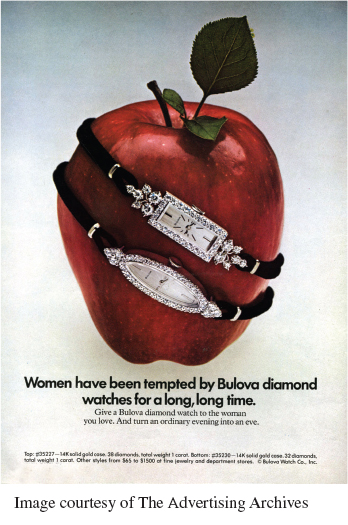

The connotative meaning of an apple in Western culture dates back to the biblical story of the Garden of Eden, where Eve, tempted by a serpent, eats the fruit from the forbidden tree of knowledge and brings about the end of paradise on earth. Throughout Western culture, apples have come to represent knowledge and the pursuit of knowledge. Think of the ubiquitous Apple logo gracing so many mobile phones, tablets, and laptops: With its prominent bite, it symbolizes the way technology opens up new worlds of knowing. Sometimes, apples represent forbidden knowledge, temptation, or seduction — and biting into one suggests giving in to desires for new understandings and experiences. The story of Snow White offers just one example of an apple used as a symbol of temptation.

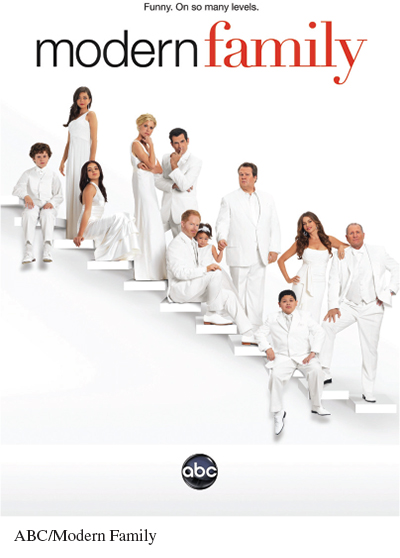

Let’s look at two additional advertisements (pictured below), each of which relies almost entirely on images rather than words. The first, an ad for a TV comedy that made its debut in 2009, boldly displays the show’s title and highlights the network name by setting it apart, but the most interesting words are in much smaller print:

Funny. On so many levels.

These words flatter the ad’s readers, thus making them susceptible to the implicit message: “Look at this program.” Why do we say the words are flattering? For three reasons:

The small type size implies that the reader isn’t someone whose attention can be caught only by headlines.

146

The pun on “levels” (physical levels, and levels of humor) is a witty way of saying that the show offers not only the low comedy of physical actions but also the high comedy of witty talk — talk that, for instance, may involve puns.

The two terse, incomplete sentences assume that the sophisticated reader doesn’t need to have things explained at length.

The picture itself is attractive, showing what seems to be a wide variety of people (though not any faces or body types that in real life might cause viewers any uneasiness) posed in the style of a family portrait. Indeed, these wholesome figures, standing in affectionate poses, are all dressed in white (no real-life ketchup stains here) and are neatly framed — except for the patriarch, at the extreme right — by a pair of seated youngsters whose legs dangle down from the levels. The modern family, we’re told, is large and varied (this one includes a gay son and his partner, and their adopted Vietnamese baby), smart and warm. Best of all, it is “Funny. On so many levels.”

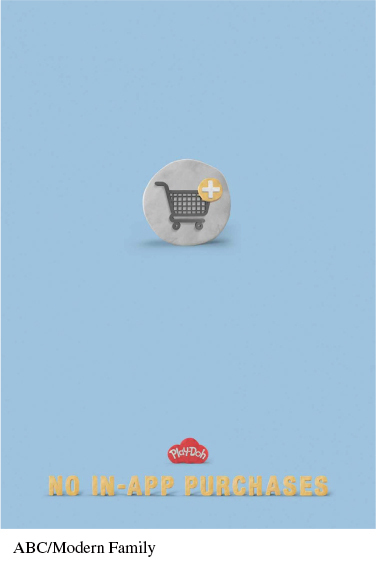

The second ad features just a single line of text: "No In-App Purchases." These words are set below the image of a shopping cart with a plus sign, which has come to be an almost universally recognized symbol for an electronic shopping cart. Both the text and the icon are textured and look a little rough at the edges, suggesting that they are made out of the very item they are advertising. After all, Play-Doh has been around since the 1930s; though the way children play has changed dramatically since then (most kids born now will grow up knowing what an "in-app purchase" is), by fashioning the electronic icon and text out of a nearly century-old product, the ad implies that just because a toy — or anything else — is new and high-tech, that does not make it inherently better than old-fashioned things. After all, the product being advertised has been around for nearly a century; how long will a new app on a smartphone or tablet last until it is replaced with a newer version?

A CHECKLIST FOR ANALYZING IMAGES (ESPECIALLY ADVERTISEMENTS)

What is the overall effect of the design? Colorful and busy (suggesting activity)? Quiet and understated (e.g., chiefly white and grays, with lots of empty space)? Old-fashioned or cutting edge?

What single aspect of the image immediately captures your attention? Its size? Its position on the page? The beauty of the image? The grotesqueness of the image? Its humor?

Who is the audience for the image? Affluent young men? Housewives? Retired persons?

What is the argument?

Does the text make a rational appeal (logos)? (“Tests at a leading university prove that . . .”; “If you believe X, you should vote ‘No’ on this referendum” appeal to our sense of reason.)

Does the image appeal to the emotions or to dearly held values (pathos)? (Images of starving children or maltreated animals appeal to our sense of pity; images of military valor may appeal to our patriotism; images of luxury may appeal to our envy; images of sexually attractive people may appeal to our desire to be like them; images of violence or of extraordinary ugliness — as in ads showing a human fetus being destroyed — may seek to shock us.)

Does the image make an ethical appeal — that is, does it appeal to our character as a good human being (ethos)? (Ads by charitable organizations often appeal to our sense of decency, fairness, and pity; but ads that appeal to our sense of prudence — such as ads for insurance companies or investment houses — also make an ethical appeal).

What is the relation of print to image? Does the image do most of the work, or does it serve to attract us and lead us on to read the text?

147

Topics for Critical Thinking and Writing

Imagine that you work for a business — for instance, a vacation resort, a clothing manufacturer, or an automaker — that advertises in a publication such as Time or Newsweek. Design an advertisement for the business: Describe the picture and write the text, and then, in an essay of 500 words, identify your target audience (college students? young couples about to buy their first home? retired persons?) and explain your purpose in choosing certain types of appeals (e.g., to reason, to the emotions, to the audience’s sense of humor).

It is often said that colleges, like businesses, are selling a product. Examine a brochure or catalog that is sent to prospective college applicants, or locate your own college’s view book, and analyze the kinds of appeals that some of the images make.