Other Aspects of Visual Appeals

148

As we saw with the uses of images relating to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, photographs can serve as evidence but have a peculiar relationship to the truth. We must never forget that images are constructed, selected, and used for specific purposes. When advertisers use images, they’re trying to convince consumers to purchase a product or service. But when images serve as documentary evidence, we often assume they’re showing the “truth” of the matter at hand. Our skepticism may be lower when we see an image in the newspaper or a magazine, assuming it captures a particular event or moment in time as it really happened. But historical images, images of events, news photographs, and other forms of visual evidence are not free from the potential for conscious or unconscious bias. Consider how liberal and conservative media sources portray the nation’s president in images: One source may show him proud and smiling in bright light with the American flag behind him, while another might show him scowling in a darkened image suggestive of evil intent. Both are “real” images, but the framing, tinting, setting, and background can inspire significantly different responses in viewers.

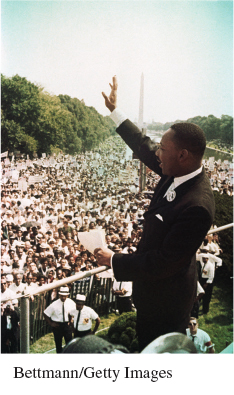

As we saw with the image of LeBron James, certain postures, facial expressions, and settings can contribute to a photograph’s interpretation. Martin Luther King Jr.’s great speech of August 28, 1963, “I Have a Dream,” still reads very well on the page, but part of its immense appeal derives from its setting: King spoke to some 200,000 people in Washington, D.C., as he stood on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. That setting, rich with associations of slavery and freedom, strongly assists King’s argument. In fact, images of King delivering his speech are nearly inseparable from the very argument he was making. The visual aspects — the setting (the Lincoln Memorial with the Washington Monument and the Capitol in the distance) and King’s gestures — are part of the speech’s persuasive rhetoric.

Derrick Alridge, a historian, examined dozens of accounts of Martin Luther King Jr. in history books, and he found that images of King present him overwhelmingly as a messianic figure — standing before crowds, leading them, addressing them in postures reminiscent of a prophet. While King is an admirable figure, Alridge asserts, history books err by presenting him as more than human. Doing so ignores his personal struggles and failures and makes a myth out of the real man. This myth suggests he was the epicenter of the civil rights movement, an effort that was actually conducted in different ways via different strategies on the part of many other figures whom King eclipsed. We may even get the idea that the entire civil rights movement began and ended with King alone. When he’s presented as a holy prophet, it becomes easier to focus on his abstract messages about love, equality, and justice, and not on the specific policies and politics he advocated — his avowed socialist stances, for instance. While photographs of King seek to help us remember, they may actually portray him in a way that causes us to forget other things — for example, the fact that his approval rating among whites at the time of his death was lower than 30 percent, and among blacks lower than 50 percent.

LEVELS OF IMAGES

149

One helpful way of discerning the meanings of images by looking at them (see Seeing versus Looking: Reading Advertisements) is to utilize seeing first as a way to define what is plainly or literally present in them. You can begin by seeing — identifying the elements that are indisputably “there” in an image (the denotative level). Then you move on to looking — interpreting the meanings suggested by the elements that are present (the connotative level).

Semioticians distinguish between images’ surface levels and deeper levels. The surface level is the syntagmatic level, and the deeper level is the paradigmatic level. The words syntagmatic and paradigmatic are related to the words syntax and paradigm.

150

Arguably, when we see, we pay attention only to the syntagmatic level. We notice the various elements included in an image. We see denotatively — that is, we observe just the explicit elements of the image. We aren’t concerned with the meaning of the image’s elements, but just with the fact that they’re present.

When we look, we move to the paradigmatic level. That is, we speculate on the elements’ deeper meanings — what they suggest figuratively, symbolically, or metaphorically in our cultural system. We may also consider the relationship of different elements to one another. When we do this, we look connotatively.

| Syntagmatic analysis | Paradigmatic analysis | |

| Seeing | Looking | |

| Denotation | Connotation | |

| Literal | Figurative | |

| What is present | What it means | |

| Understanding / Textual | Interpreting / Subtextual / Contextual |

Exercise

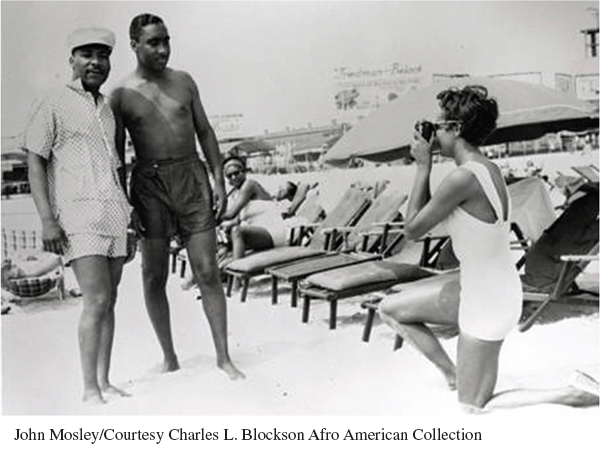

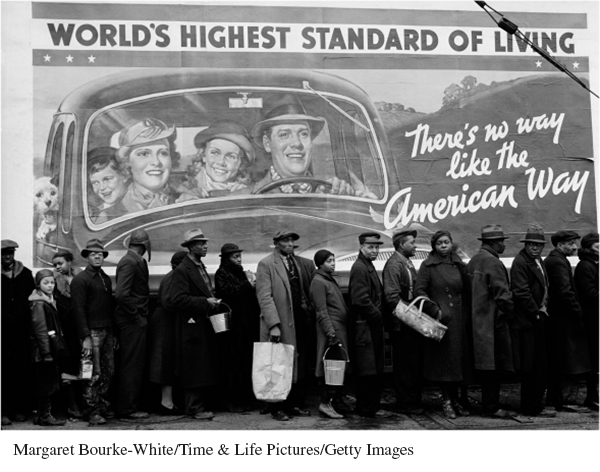

Examine the two images below. As you examine each one, do the following:

See the image. Perform a syntagmatic analysis thoroughly describing the image elements you observe. Write down as many elements as possible that you see.

Look at the image. Perform a paradigmatic analysis in which you take the elements you have observed and relate what they suggest by considering their figurative meanings, their meanings in relation to one another, and their meanings in the context of the images’ production and consumption.

151

The point here is that photographs promise a clear window into a past reality but are not unassailable guarantors of truth. In the digital age, it’s remarkably easy to alter photographs, and we have become more suspicious of photographs as direct evidence of reality. Yet we still tend to trust certain sources more than others. To counteract this tendency, we can be more critical about images by asking three overarching questions about the contexts in which they are created, disseminated, and received. Within each question, other questions arise.

Who produced the image? Who was the photographer? Under what circumstances was the picture taken? How is the subject of the image framed? What other visual information is included in the frame? What is emphasized and de-emphasized? What do you think is the image’s intended effect?

A RULE FOR WRITERS If you think that pictures will help you to make the point you are arguing, include them with captions explaining their sources and relevance.

Who distributed the image? How widely has the image been distributed? Where has it been published (magazine, newspaper, blog, social media page)? What is the intended audience of the publication where the image appears? What purpose does the image serve? How does the image support the accompanying text? What alternative images exist?

Who consumed the image? What type of audience is the likeliest viewer of the image? Are they likely to see it as negative or positive? Does the image inspire an emotional response? If so, what kind? What elements in the photograph are likely to generate certain kinds of responses?