Historical Background

Timeline

| 1541 | Arrival of Spanish conquistador Coronado; first recorded contact between native peoples and Europeans on the central plains. |

| Late 1700s | Cheyennes and Arapahoes migrate to the Colorado plains from the western Great Lakes. |

| 1803 | Louisiana Purchase makes the Colorado plains part of the United States. |

| 1830s | Plains Indians increasingly active in fur trade with American merchants. William and Charles Bent establish trading post, Bent’s Fort, on the Arkansas River along the Santa Fe Trail. |

| 1845–1848 | Annexation of Texas, the Oregon Treaty with England, and the War with Mexico expands the United States to the Pacific; American migration across the plains to Oregon and California intensifies. |

| 1851 | Treaty of Fort Laramie recognizes the eastern Colorado plains as Cheyenne and Arapaho homeland. |

| 1858 | Gold is discovered at what would become Denver; surge in white population. |

| 1859 | Fort Lyon (originally Fort Wise) is founded forty miles southwest of Sand Creek site. |

| 1859–1863 | Tensions increase between Plains Indians and white population. |

| 1861 | American Civil War begins; Treaty of Fort Wise restricts Cheyennes and Arapahoes to a much smaller reservation in southeastern Colorado. |

| April–May 1864 | After unprovoked attacks by military, some Indian reprisals. |

| June 1864 | Indians are suspected in murder of family of white settlers. Governor Evans issues proclamation ordering all peaceful Indians to report to military forts, with orders to “hunt out and punish” those who do not; few Indians comply. |

| July 1864 | Raids by Indians in Nebraska and Kansas. Supply lines to Colorado are disrupted; panic in Denver. |

| August 1864 | Governor Evans authorizes private citizens to pursue hostile Indians and recruits a volunteer regiment, Third Colorado Cavalry, for one hundred days of service to defend against Indians. |

| September 1864 | Black Kettle sends letter requesting peace; Major Wynkoop offers to take Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders to Denver to discuss peace; Council at Camp Weld is reluctantly held by Governor Evans with Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs and Colonel Chivington. |

| October 1864 | Cheyenne band led by Black Kettle reports to Fort Lyon and is told to camp at Sand Creek; Arapahoes camp farther down Arkansas River. Wynkoop is replaced as commander at Fort Lyon by Major Scott Anthony. |

| November 29, 1864 | Attack on Sand Creek. |

| January–May 1865 | Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War investigates Sand Creek. |

From soon after the first colonies were established on the Atlantic coast early in the seventeenth century, Europeans and their descendants were sometimes in friendly, mutually beneficial relations with native peoples and sometimes at war, but the overall story was one of conquest and dispossession. It is not a simple story. There were many causes for conflict. But the basic reason was the desire and need of what became a large and growing population of newcomers for the land and resources of the many Indian peoples who had lived there for thousands of years. At the time, Americans typically described Indian wars as heroic and necessary for the nation’s progress. Always, however, some believed the opposite: that conflicts could and should be resolved peacefully and that military actions against native peoples represented unnecessary aggression. A case in point was the attack at Sand Creek.

The Great Plains has been home to Indian peoples and their ancestors for at least twelve thousand years. The arrival of Europeans in the sixteenth century brought profound changes, among them horses acquired from Spanish settlements in New Mexico after 1680. On horseback Indians could range farther, trade more extensively, hunt more efficiently, especially among the vast herds of bison, and wage war more terribly. One result of the introduction of horses was the migration of peoples onto the plains, drawn by the promise of a new life on one of the largest and richest pastures on earth. Among them were the Cheyennes and the Arapahoes, who came originally from the western Great Lakes and by the 1820s occupied the high plains of Wyoming and Colorado.

Change quickened again when white Americans began trapping and trading in the area. Eastern and European demand for robes made of bison hides offered Indians an especially alluring opportunity. At Bent’s Fort, an adobe compound established in 1833 on the Arkansas River in southeastern Colorado, Cheyennes and Arapahoes exchanged robes for eastern goods and developed close ties to white traders like William Bent. Closer relations also brought troubles. The bison population began to decline. Whites crossing the plains to the far West brought diseases like cholera that reduced some Cheyenne bands by as much as half.

A far greater — and for Indians a catastrophic — change began in the summer of 1858 when prospectors found gold at the site of modern Denver. The next year tens of thousands of persons flocked to the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains and soon began to settle also along the Platte and Arkansas Rivers. As the newcomers built towns and started farms and ranches, they disrupted the Indian way of life that relied on hunting and moving freely over great distances. The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) had recognized the eastern Colorado plains as Cheyenne and Arapaho homeland. Authorities now negotiated a new treaty at Fort Wise that opened the area to white settlement and provided a far smaller reservation for the two tribes on the Arkansas River. Negotiations, however, were with only a few Indian leaders, and most bands refused to recognize it. The situation worsened in the spring and summer of 1864 with a series of clashes, some precipitated by army troops. With many soldiers called away to fight in the Civil War, Governor John Evans was allowed to recruit a regiment of Coloradans into service for a hundred days to fight Indians. They were under the command of Colonel John Chivington, an officer with both political and military ambitions and a low opinion of Indians.

In August 1864, a prominent Cheyenne, Ochinee (One Eye) appeared at Fort Lyon, a military post on the Arkansas River. He was carrying a letter from Chief Black Kettle, who feared that his band of Cheyenne would be attacked. U.S. agents advised Black Kettle and his people to settle along Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado, which they agreed to do until a peace treaty could be signed. On November 29, 1864, while many of the Cheyenne and Arapaho men were out hunting, the Colorado militia under the command of Colonel Chivington attacked the camp at Sand Creek, slaughtering about two hundred mostly women, children, and elderly.

In 1865, an investigation by the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War decried the violence at Sand Creek. By then, both Colonel Chivington and Governor John Evans had resigned, and no charges were ever filed against the perpetrators of the attack. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other tribes of the plains would continue to face pressures from the U.S. military. Confined to ever smaller reservations, and violently punished for not agreeing to be “civilized,” the final blow to their traditional ways of life would come with the slaughter of the great buffalo herds of the plains between 1867 and 1883.

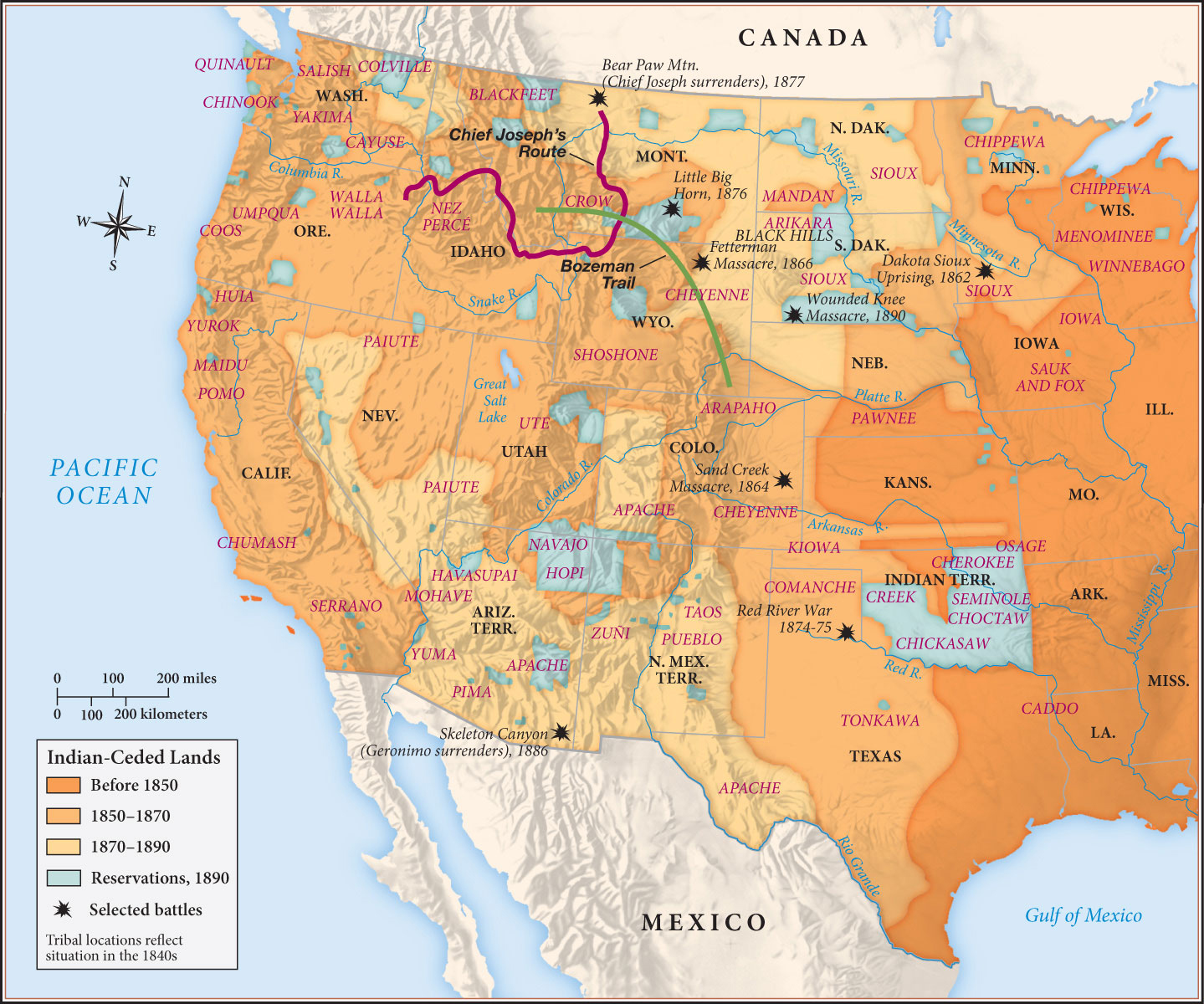

Conflicts with the United States and Indian Land Cessions, to 1890