Historical Background

Timeline

| 1869 | Knights of Labor is founded. |

| 1875–1877 | Amid a severe depression, the first Farmers Alliances are founded in various parts of the United States. |

| 1877 | Reconstruction ends. |

| 1884–1885 | Peak of Knights of Labor influence and membership. |

| 1886 | Anarchist violence at Haymarket Square in Chicago is used to discredit the labor movement nationwide. |

| late 1880s | Severe drought impacts farmers in the Great Plains. |

| 1888 | African American farmers in the South — barred from joining the Southern Farmers Alliance — form a separate National Colored Farmers Alliance; Republican Benjamin Harrison is elected president. |

| 1890 | People’s Party is created in Kansas; victories in Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota in the November elections. |

| 1892 | National People’s Party is founded; Democrat Grover Cleveland wins presidential election, but People’s Party candidate James B. Weaver wins 8.5 percent of the popular vote and 22 electoral votes. |

| 1893 | Severe economic depression hits urban and industrial areas. |

| 1894 | Major Republican gains in midterm congressional elections; U.S. Supreme Court strikes down progressive federal income tax, which had been passed by Congress and signed by President Cleveland. |

| 1896 | Democrats nominate William Jennings Bryan for president on a reform platform; People’s Party endorses Bryan’s nomination; Republican William McKinley wins the November election. |

| 1900 | McKinley is elected for a second term; Populist Party fades. |

| 1901 | McKinley is assassinated; Theodore Roosevelt brings some Populist reform ideas (such as antitrust) to prominence in the White House. |

The People’s Party movement of the 1890s, also known as Populism, was one of the great political revolts in U.S. history. Angry at the economic hardships they faced and what they perceived as broader economic injustices, a coalition of rural and working-class Americans rejected the policies of the two major parties, Republicans and Democrats, and demanded sweeping change. Offering a radical critique of unregulated capitalism, they called for greater government intervention in the economy. The party was built by several existing institutions. The most important included a coalition of Farmers Alliances, created to bring rural people together for mutual education and support, and the Knights of Labor, a broad-based labor union that sought to include both skilled and unskilled laborers, tenant farmers, domestic servants, and many other workers. The Farmers Alliance was especially popular among southern cotton growers, who faced an extraordinary plunge in prices for their crop, and on the Great Plains, where a severe drought wreaked terrible hardship.

In the 1880s, both of these groups experimented with cooperatives: nonprofit stores, insurance companies, and other ventures that eliminated middlemen and gave farmers an advantage in the marketplace. But they were disadvantaged by their limited financial resources, and many of these projects failed. At the same time, local assemblies of the Knights of Labor engaged in high-profile strikes that were ultimately defeated. Violence at Chicago’s Haymarket Square in 1886, apparently perpetrated by radical anarchists, was blamed on the entire labor movement and contributed to corporations’ rollback of the Knights of Labor.

The Farmers Alliance and Knights of Labor argued that only government intervention could address some of the issues that concerned them, such as banking and monetary policy, discriminatory railroad rates, and inequalities of wealth. Reformers in Kansas, which since the Civil War had been fiercely Republican, led the way in 1890, creating a new party they called the People’s Party. Stunning the nation, Populist candidates won control of the lower house of the Kansas legislature and five of the state’s seven congressional seats. Nebraska also sent two Populists to the House of Representatives in Washington, D.C.; Minnesota sent one; and Nebraska and Kansas each sent a Populist U.S. senator.

Impressed by these gains, leaders of the Farmers Alliance and Knights of Labor called for a national movement. Meeting in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1892, the new People’s Party nominated former Union general James B. Weaver for president. Weaver captured more than one million votes (8.5 percent of the total), and the Populists again secured a modest delegation in Congress.

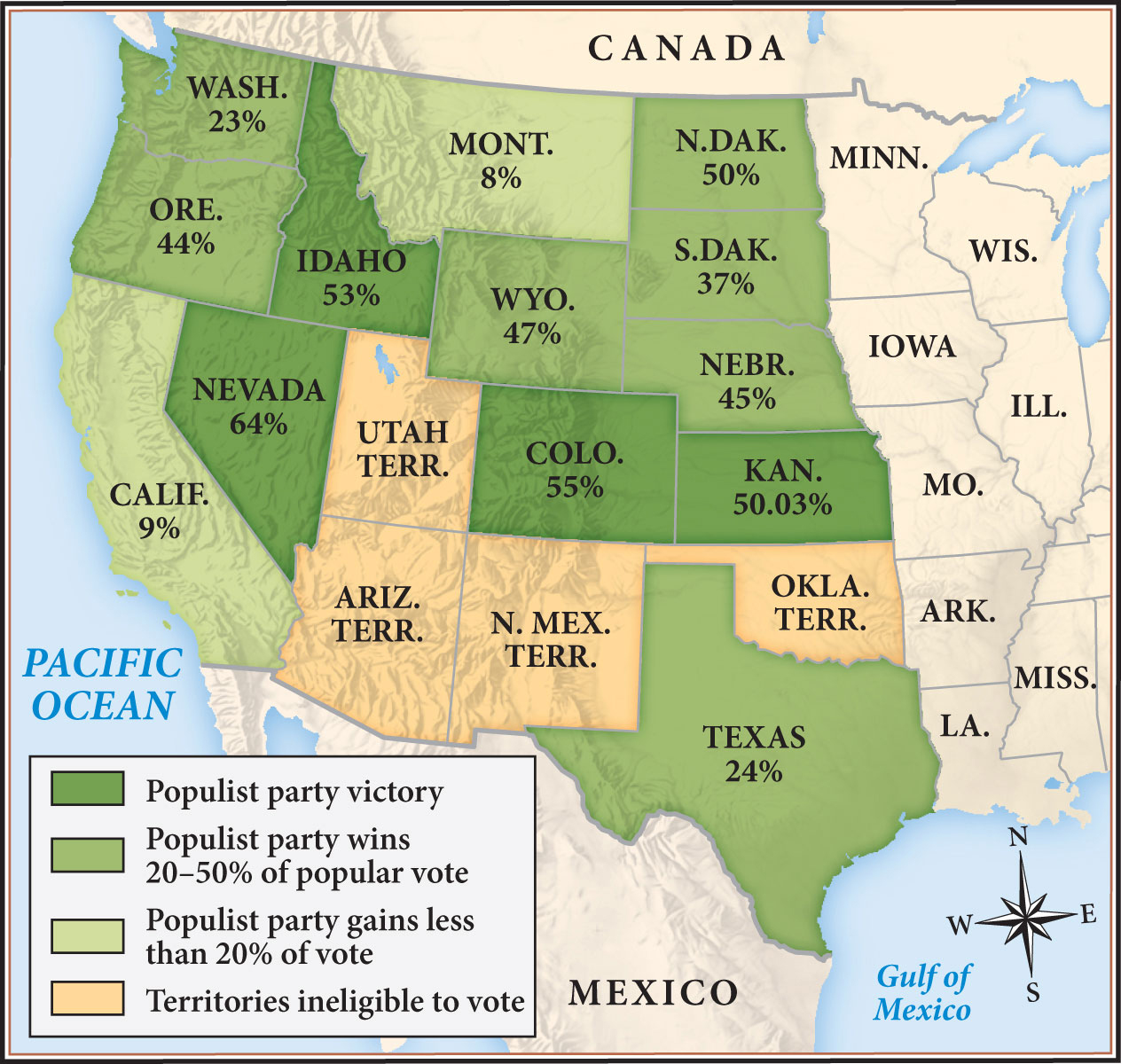

But the Populists had difficulty reaching beyond their strongholds in the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain states, and they failed to persuade large portions of the urban working class to support the movement’s cause. In southern states such as Georgia and Alabama, where the People’s Party had large numbers of both white and African American supporters, Democrats engaged in flagrant fraud, intimidation, and violence to “count the Pops out” and ensure Democratic victory. In the election of 1894, a majority went to the polls and elected Republicans, who became the dominant party for the next fifteen years.

Despite its limits, the People’s Party left important political legacies. The most immediate was its impact on the Democratic Party, which in 1896 began to adopt a few selected planks from Populist platforms — such as the call for a graduated federal income tax, aimed primarily at the wealthiest 5 percent. They chose as their presidential nominee a young reform-minded Nebraska Democrat named William Jennings Bryan, and the People’s Party seconded his nomination. This spelled the end of Populism, as the party’s energies bent to elect a Democrat, and Bryan did not win. But the shift demonstrated that Populist ideas could live on in major parties’ platforms. People’s Party leaders, interviewed many years after their political revolt, often noted that many planks of the Omaha platform had eventually become national policy.

The Heyday of Western Populism, 1892