Presenting Your Critical Thinking

For more on taking a stand, see Ch. 9; on proposals, see Ch. 10; on evaluation, see Ch. 11; and on supporting a position, see Ch. 12.

Why do you have to worry about critical thinking? Isn’t it enough just to tell everybody else what you think? That tactic probably works fine when you casually debate with your friends. After all, they already know you, your opinions, and your typical ways of thinking. They may even find your occasional rant entertaining. Whether they agree or disagree, they probably tolerate your ideas because they are your friends.

When you write a paper in college, however, you face a different type of audience, one that expects you to explain what you assume, what you advocate, and why you hold that position. That audience wants to learn the specifics — reasons you find compelling, evidence that supports your view, and connections that relate each point to your position. Because approaches and answers to complex problems may differ, your college audience expects reasoning, not emotional pleading or bullying or preaching.

How you reason and how you present your reasoning are important parts of gaining the confidence of college readers. College papers typically develop their points based on logic, not personal opinions or beliefs. Most are organized logically, often as a series of reasons, each making a claim, a statement, or an assertion that is backed up with persuasive supporting evidence. Your assignment or your instructor may recommend ways such as the following for showing your critical thinking.

See A in the Quick Research Guide for more about the statement-support pattern.

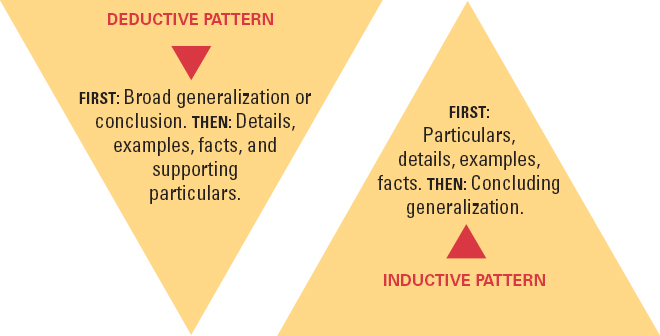

Reasoning Deductively or Inductively. When you state a generalization, you present your broad general point, viewpoint, or conclusion.

The admissions requirements at Gerard College are unfair.

On the other hand, when you supply a particular, you present an instance, a detail, an example, an item, a case, or other specific evidence to demonstrate that a general statement is reasonable.

A Gerard College application form shows the information collected by the admissions office. Under current policies, standardized test scores are weighted more heavily than better predictors of performance, such as high school grades. Qualified students who do not test well often face a frustrating admissions process, as Irma Lang’s situation illustrates.

Your particulars consist of details that back up your broader point; your generalizations connect the particulars so that you can move beyond isolated, individual cases.

For more about thesis statements, see Ch. 20.

Most college papers are organized deductively. They begin with a general statement (often a thesis) and then present particular cases to support or apply it. Readers like this pattern because it reduces mystery; they learn right away what the writer wants to show. Writers like this pattern because it helps them state up front what they want to accomplish (even if they have to figure some of that out as they write and state it more directly as they revise). Papers organized deductively sacrifice suspense but gain directness and clarity.

See more on inductive and deductive reasoning.

On the other hand, some papers are organized inductively. They begin with the particulars — a persuasive number of instances, examples, or details — and lead up to the larger generalization that they support. Because readers have to wait for the generalization, this pattern allows them time to adjust to an unexpected conclusion that they might initially reject. For this reason, writers favor this pattern when they anticipate resistance from their audience and want to move gradually toward the broader point.

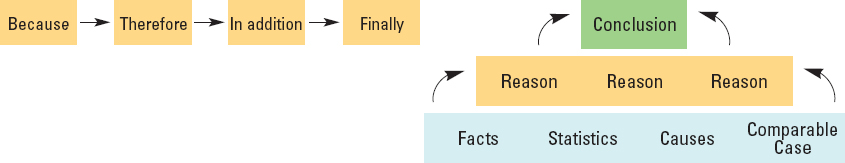

Building Sequences and Scaffolds. You may use several strategies for presenting your reasoning, depending on what you want to show and how you think you can show it most persuasively. You may develop a line of reasoning, a series of points and evidence, running one after another in a sequence or building on one another to support a persuasive scaffold.

For more strategies for developing, see Ch. 22.

Developing Logical Patterns. The following patterns are often used to organize reasoning in college papers. They can help show relationships but don’t automatically prove them. In fact, each has advantages but may also have disadvantages, as the sample strengths and weaknesses illustrate.

Pattern: Least to Most

Advantage: Building up to the best points can produce a strong finish.

Disadvantage: Holding back on strong points makes readers wait.

Pattern: Most to Least

Advantage: Beginning with the strongest point can create a forceful opening.

Disadvantage: Tapering off with weaker points may cause readers to lose interest.

For more on comparison and contrast, see Ch. 7.

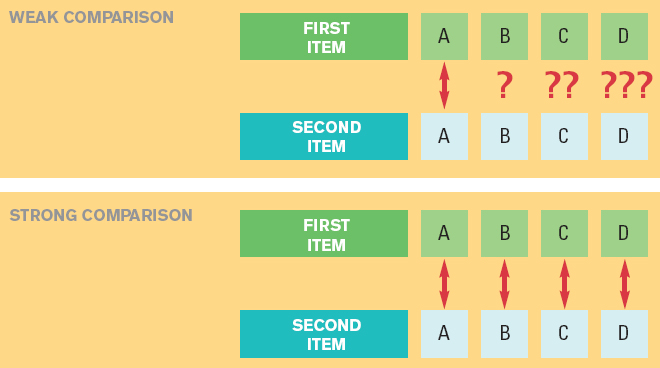

Pattern: Comparison and Contrast

Advantage: Readers can easily relate comparable points about things of like kind.

Disadvantage: Some similarities or differences don’t guarantee or prove others.

For more on cause and effect, see Ch. 8.

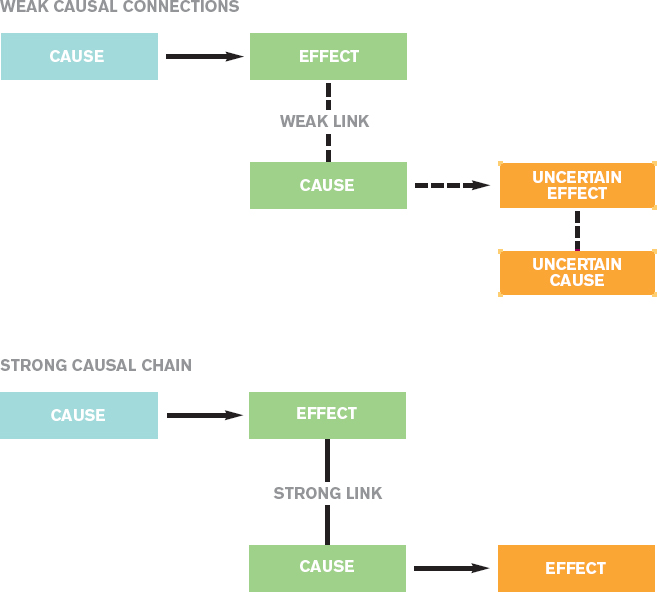

Pattern: Cause and Effect

Advantage: Tracing causes or effects can tightly relate and perhaps predict events.

Disadvantage: Weak links can call into question all relationships in a series of events.

| Sound Reasoning | Weak Reasoning | |

| Comparisons | Comparison that uses substantial likeness to project other similarities: | Inaccurate comparison that relies on slight or superficial likenesses to project other similarities: |

| Like the third graders in the innovative reading programs just described, the children in this town also could become better readers. | Like kittens eagerly stalking mice in the fields, young readers should gobble up the tasty tales that were the favorites of their grandparents. | |

| Causes and Effects | Causal analysis that relies on well-substantiated and specific connections relating events and outcomes: | Faulty reasoning that oversimplifies causes, confuses them with coincidences, or assumes a first event must cause a second: |

| City water reserves have suffered from below-average rainfall, above-average heat, and steadily increasing consumer demand. | One cause — and one alone — accounts for the ten-year drought that has dried up local water supplies. | |

| Reasons | Logical reasons that are supported by relevant evidence and presented with fair and thoughtful consideration: | Faulty reasons that rely on bias, emotion, or unrelated personal traits or that accuse, flatter, threaten, or inspire fear: |

| As the recent audit indicates, all campus groups that spend student activity fees should prepare budgets, keep clear financial records, and substantiate expenses. | All campus groups, especially the arrogant social groups, must stop ripping off the average student’s fees and threatening to run college costs sky high. | |

| Evidence | Evidence that is accurate, reliable, current, relevant, fair, and sufficient to persuade readers: | Weak evidence that is insufficient, dated, unreliable, slanted, or emotional: |

| Both the statistics from international agencies and the accounts of Sudanese refugees summarized earlier suggest that, while a fair immigration policy needs to account for many complexities, it should not lose sight of compassion. | As five-year-old Lannie’s frantic flight across the Canadian border in 1988 proves, refugees from all the war-torn regions around the world should be welcomed here because this is America, land of the free. | |

| Conclusions | Solid conclusions that are based on factual evidence and recognize multiple options or complications: | Hasty conclusions that rely on insufficient evidence, assumptions, or simplistic two-option choices: |

| As the recent campus wellness study has demonstrated, college students need education about healthy food and activity choices. | The campus health facility should refuse to treat students who don’t eat healthy foods and exercise daily. |