Planning, Drafting, and Developing

For more strategies for planning, drafting, and developing papers, see Chs. 20, 21, and 22.

Now, how will you tell your story? If the experience is still fresh in your mind, you may be able simply to write a draft, following the order of events. If you want to plan before you write, here are some suggestions.

See more on stating a thesis.

Start with a Main Idea, or Thesis. Jot down a few words that identify the experience and express its importance to you. Next, begin to shape these words into a sentence that states its significance — the main idea that you want to convey to a reader. If you aren’t certain yet about what that idea is, just begin writing. You can work on your thesis as you revise.

For practice developing effective thesis statements, go to the interactive “Take Action” charts in Re:Writing.

| TOPIC IDEA + SLANT | reunion in Georgia + really liked meeting family |

| WORKING THESIS | When I went to Georgia for a family reunion, I enjoyed meeting many relatives. |

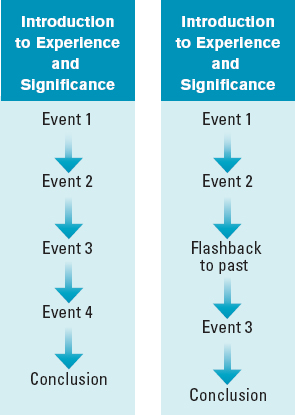

Establish Your Chronology. Retelling an experience is called narration, and the simplest way to organize is chronologically — relating the essential events in the order in which they occurred. On the other hand, sometimes you can start an account of an experience in the middle and then, through flashback, fill in whatever background a reader needs to know.

Richard Rodriguez, for instance, begins Hunger of Memory (Boston: David R. Godine, 1982), a memoir of his bilingual childhood, with an arresting sentence:

I remember, to start with, that day in Sacramento, in a California now nearly thirty years past — when I first entered a classroom, able to understand about fifty stray English words.

The opening hooks our attention. In the rest of his essay, Rodriguez fills us in on his family history, on the gulf he came to perceive between the public language (English) and the language of his home (Spanish).

See more on providing details.

Show Your Audience What Happened. How can you make your recollections come alive for your readers? Return to Baker’s account of Mr. Fleagle teaching Macbeth, Schreiner’s depiction of his cousin putting the wounded rabbits out of their misery, or Chackowicz’s experiences. These writers have not merely told us what happened; they have shown us, by creating scenes that we can see in our mind’s eye.

For practice supporting a thesis, go to the interactive “Take Action” charts in Re:Writing.

As you tell your story, zoom in on at least two or three specific scenes. Show your readers exactly what happened, where it occurred, what was said, who said it. Use details and words that appeal to all five senses — sight, sound, touch, taste, smell. Carefully position any images you include to clarify visual details for readers. (Be sure that your instructor approves such additions.)